![]()

Chapter 1

A Radical Change: from Pride to Misery, from the Levant Company to the Foreign Office

In 1820 a British consular representation, albeit of a very limited kind, already existed in the Aegean. it had been set up by the Levant Company for the purpose of protecting its traders in the territory of the Ottoman Empire. The consuls were merchants, chosen and elected by other merchants within the Company. The representation was confined to the commercial aspect of the British presence in the Levant and it worked very efficiently almost until the winding-up of the Company in 1825.

When the administration of the Ionian islands became the responsibility of the British Government in 1815, the consular service in the Aegean was dramatically affected by the changed nature of consular work and the vastly increased burden on the consuls. it became clear, at this point, that the scope of the service in this part of Europe should be redefined. So, between 1815 and the eventual takeover of the consular service in the Levant by the Foreign Office in 1825, the Government paved the way for the closure of the Levant Company’s representation.

The change of administration substantially affected the nature, the scope and ultimately the role of the consular service, as well as the work and the life-style of the consuls themselves. The reorganisation was a long, protracted process which lasted over fifteen years. To understand the nature, and significance, of the changes, it is necessary to compare the organisation and development of the Levant Company representation with that of the later consular service under the Foreign Office.

* * *

The history of the consular service in the Aegean can be seen to have begun with the founding of the Levant Company in 1553 when the merchant and explorer Anthony Jenkinson, then resident at Aleppo, obtained privileges known as capitulations1 from the Sultan, permitting trade with the Levant.2 It was the first time that England had been engaged in commercial relations with the Ottoman Empire. In 1581 Queen Elizabeth confirmed these privileges by granting a seven year charter to a group of English merchants, and the following year she sent an ambassador to Turkey with the task of establishing residential compounds called factories for the merchants. The ambassador remained in the Levant for twelve years and, on his return, Elizabeth granted a second charter to the merchants, this time for twelve years. In 1605 King James extended the charter ‘for ever’3 to the merchants, their sons, and to any other of the King’s subjects, on payment of a fee of £25 each before the age of twenty seven, and £50 thereafter. It was at this point that the ‘Company of merchants of England trading into the Levant seas’ was founded. It was granted the power to appoint consuls and to assess duties upon merchandise and ships. The charter was confirmed by Charles II in 1660, and the duties charged by the Company were authorised by various acts of Parliament, notably in 1753 and 1819.4 duty was never levied on ships, but a tariff of up to 3 per cent was charged on merchandise to cover the expenses of transport and of diplomatic representation. The 1819 act was promoted by the Government ‘to remove doubts respecting the dues payable to the Levant Company’, indicating that tension was rising over the right of trade in the Levant waters.

British merchants in the Levant, ‘the most opulent as well as amongst the most respectable traders’,5 resided in the factories established just outside the commercial towns, in specific areas or frank quarters where they reproduced, as far as possible, the British way of life. John Oliver Hanson, who stopped at Smyrna during his travels in the Levant, wrote an interesting account of the British factory there in 1813, in which he also described the consular representation:

The European nations at Smyrna are each represented by their respective Consuls. The Factories which are established there at present consist of the English, French, Russian, Dutch, Austrian, and Spanish. The English is the most considerable in point of wealth, respectability and power, its consul is the most feared, and looked up to. As is natural, a great spirit of jealousy and rivalship [sic], perpetually exists between the English and French factories … The English Consul [Francis Werry] who has now held his situation for many years is a man of great firmness and respectability. In several instances he has shown no ordinary talent in the administration of the duties of his office, and has on one or more occasions, at great personal risque, upheld the rights and privileges of his nation. The British factory consists of about sixteen or eighteen mercantile establishments who act principally as agents to Merchants in England. The principal trade to Smyrna consists in the importation of Manufactured Cottons, Stuffs, refined Sugar, Coffee, Dye Woods, Spices, Tin, Indigo. Its principal exports are, Silk, Cotton wool, Madder roots, Galls, sponges, Mohair Yarn, Yellow Berries and various sorts of gum. from a long residence there, many of the Merchants have become as if it were naturaliz’d in the place. Many of them speak Turkish, all of them Greek, French and Italian. Most of them are married to women of the country and display much elegance, and hospitality, in the arrangement of their houses and their reception of Travellers.6

Merchants usually spent a period of twenty years in the Levant, the first eight of which were passed learning the trade under the supervision of another merchant. On his retirement, the older merchant would leave the business in the hands of a younger member who, as an associate, would thus be obliged to share profits with his predecessor. When merchants returned to England at the end of their time in the Levant, their incomes assured by the younger partner, they were usually wealthy men, able to afford a grand house in the country with a large retinue. In 1682 George Wheler described this very point when talking of the British Factory at Smyrna:

The English Factory consist of fourscore, or an hundred Persons, most of them younger Sons to Gentlemen; who give three or four hundred pounds to some great Merchant of the Levant Company; and bind their Sons Apprentices for seven Years; three whereof they serve at London, to understand their Masters Concerns: and then their Masters are obliged to send them to negotiate in these Parts, and to find them Business; out of which they are allowed a certain Sum, per Cent.: Where by their Industry, in Traffick [sic] for themselves also, upon Good gains, but little Loss, they live gentilely, become rich, and get great estates in a short time, if they will be but indifferent good Husbands, and careful of their Owners, and their own business. 7

The acceptance of young members into the company was dependent upon their ability to bring a large share of capital to their associates, effectively confining access to a few already wealthy individuals. This restriction was the cause of much debate, since it excluded access to the Company to all but a few, in contradiction of the original charter which had stated that ‘any’ of the King’s subjects should be admitted to trade. Inx the long term, this issue would create problems for the survival of the company itself.

At its inception the Levant Company established consuls in the principal ports and towns of Turkey with instructions to govern and protect British persons and property and to look after their judicial affairs.8 The terms of the capitulations were such that British subjects in the Levant were forbidden from appealing to Turkish justice except in cases where an Ottoman subject was involved. Consuls had, therefore, to act judicially as well as ‘magisterially’ within their district,9 with sentencing being referred to the Consul General at Constantinople. Prior to the extension of British protection to the subjects of the Ionian islands, it would seem that the consuls were never called on to exercise jurisdiction in criminal cases.10

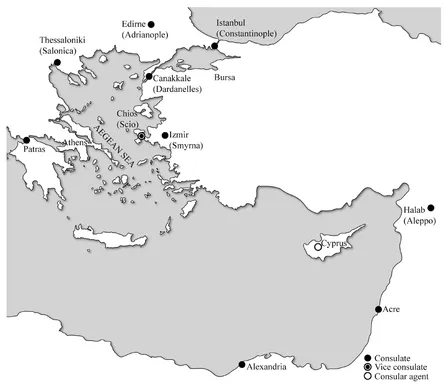

Over the 256 years of its existence, the Levant Company established just ten consulates in the area covered by its merchants; vice consuls and consular agents were to be found in a few remote islands of the Aegean, and although they were generally appointed by the ambassador at the suggestion of the consuls, the Company kept no record of their names.11 Thus, at the time of its dissolution, the Company was officially responsible for only eight consuls and five vice consuls and consular agents. Whilst consuls were normally appointed by the King, at the nomination of the Company and its representative at the Porte,12 in the Aegean archipelago they were more often appointed by the ambassador in his capacity as the King’s representative.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Levant Company Consulates

Diplomatic lifestyle in the near East under the Levant Company was of a very high standard. Consuls, being appointed for purely commercial reasons to safeguard British trade and capitulations, were allowed to trade,13 and many chose to do so. This allowed them to reside in the factories, where goods were shipped directly from Britain; their houses, together with a retinue of servants and clerks, were paid for by the Company. The ambassador was resident at Constantinople where he maintained an even larger retinue.

In comparison, the consuls in the Morea, Alexandria and Cyprus, were not paid a salary, but were instead allowed to retain a share of the consulages;14 the chancelliers, clerks employed to look after the accounts and transcribe dispatches, were also allowed to retain part of these fees, in lieu of a salary.

The Levant Company appointed interpreters, or dragomans, to help its diplomats in dealing with the local merchants and population. With the exception of the dragomans at the embassy at Constantinople and at the consulate of Smyrna, these interpreters were not paid by the Company. Instead, in exchange for their services, they obtained the right to British protection and were consequently exempted from ottoman taxation, and enjoyed the privileges of the British capitulations.

The Levant Company was, though, responsible for the payment of the salaries of the consul general, consuls, vice consuls, chaplains, surgeons, agents and the many other people employed by it, and, until the beginning of the nineteenth century, was required to pay the expenses of the ambassador and his retinue. Covered by raising capital from members of the Company, these expenses, and especially the significant cost of ambassadorial representation, were later repaid to them through the waiving of customs duties. This arrangement became strained however, when the Russo-Turkish war in 1768 caused the closure of the Bosphorus straits. The consequent economic damage to the Levant Company merchants was compounded by the terms of the Treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji (Küçük Kajnarca) of 1774, which brought the war to an end but which granted Russia extensive commercial privileges as well as parts of the Khanate of the Crimea, thus ending the Ottoman Empire’s complete control over the Bosphorus straits. 15

Trade with the Levant declined to such an extent that the Levant Company was forced to apply to Parliament for assistance. Grants were obtained to help it through its financial difficulties and, between 1768 and 1808, it received a total of £110,000 in contributions from Parliament. In 1805 the Company successfully petitioned Parliament to be relieved of the cost of ambassadorial representation, claiming that no other branch of public life had such expenses.16 Indeed, support of the ambassador alone was costing the Company more than the money granted by Parliament. It thus appointed a consul general at Constantinople to look after commercial matters and supervise the consuls. The Company’s finances improved somewhat when, in 1809, Britain’s commercial position in the Ottoman Empire was restored following an agreement which saw the restitution by France to Turkey of the Ionian Islands.17 This caused the company’s trade and revenue to increase, allowing it to reduce the rates of duty, increase the salaries of its officers, and accumulate capital.

* * *

Throughout th...