eBook - ePub

Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities

- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities

About this book

While written sources on the history of Greece have been studied extensively, no systematic attempt has been made to examine photography as an important cultural and material process. This is surprising, given that Modern Greece and photography are almost peers: both are cultural products of the 1830s, and both actively converse with modernity. Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities fills this lacuna. It is the first inter-disciplinary volume to examine critically and in a theorised manner the entanglement of Greece with photography. The book argues that photographs and the photographic process as a whole have been instrumental in the reproduction of national imagination, in the consolidation of the nation-building process, and in the generation and dissemination of state propaganda. At the same time, it is argued that the photographic field constitutes a site of memory and counter-memory, where various social actors intervene actively and stake their discursive, material, and practical claims. As such, the volume will be of relevance to scholars and photographers, worldwide. The book is divided into four, tightly integrated parts. The first, 'Imag(in)ing Greece', shows that the consolidation of Greek national identity constituted a material-cum-representational process, the projection of an imagery, although some photographic production sits uneasily within the national canon, and may even undermine it. The second part, 'Photographic narratives, alternative histories', demonstrates the narrative function of photographs in diary-keeping and in photobooks. It also examines the constitution of spectatorship through the combination of text and image, and the role of photography as a process of materializing counter-hegemonic discourses and practices. The third part, 'Photographic matter-realities', foregrounds the role of photography in materializing state propaganda, national memory, and war. The final part, 'Photographic ethnographiesâ

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities by Philip Carabott, Yannis Hamilakis, Eleni Papargyriou, Philip Carabott,Yannis Hamilakis,Eleni Papargyriou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Imag(in)ing the Nation

1

The Three-way Mirror: Photography as Record, Mirror and Model of Greek National Identity

Classical landscape with columns

From its earliest appearance, photography in Greece participated, perhaps to a greater extent and certainly more directly than any medium other than the written word, in the never-ending enterprise of nation building. This was a far from clearly defined, complex and manifold endeavour: the idea of the nation had to be simultaneously identified, defined, fabricated and promoted. Photography was in many ways ideally suited at least to the latter three of these tasks. At one and the same time, photography provided society with a record, a mirror and a model.

The role of photography familiar to all is that of recorder; individual members of society and the Greek state itself both realised that photography seemed to offer the promise of an accurate and apparently unbiased record of achievement. At the same time, photography held up a mirror to the nation, artfully displaying the face it most wanted to see reflected; the resulting images, however distorted by wishful thinking, represent an accurate record of a society’s aspirations. For example, the enormous popularity of photographic representations of the transhumant pastoralists of the Pindus in the 1950s clearly mirrored a yearning for a national origin myth rooted in the supposed innocence, simplicity and freedom of life in the high mountains.1

The contribution of photography to the construction of national identity is not of course a specifically Greek phenomenon, and similar narratives could no doubt be constructed for most countries. However, the fact that the history of modern Greece and that of the photographic medium share roughly the same time span, as well as the accidents of history and geography which made of Greece such a late developer amongst European nations, have resulted in an unusually dense and rich interpenetration of photography and history.

The Greek state which came into being as a result of what was to become known as the revolution of 1821, that uneasy mixture of national uprising, civil war, class conflict and ethnic cleansing, was itself inevitably a strange hybrid of very uncertain identity. The new state was, in truth, a disparate assemblage under whose always uncertain authority were gathered uneasily together cosmopolitan merchants and illiterate peasants, semi-piratical island shipowners and feudal primates, great landowners and expatriate intellectuals, idealists and gangsters. Furthermore, its actual and future citizens were scattered over an area greater by far than its original core. What was to provide the necessary unifying factor, now that the mirage of a supranational pan-Balkan federation had been finally laid to rest? As Robert Shannan Peckham (2001: 6) puts it, ‘in part because of the wide geographical distribution of the Greeks in diasporic communities […], language and religion, rather than affiliation to a distinct territory, became the chief determinants of Greek national identity’.

Language and faith were indeed the obvious unifying factors, but they were not without their own problems; in the mid-nineteenth century, many citizens of the new state – and of the provinces it was to acquire in the near future – spoke Greek, if they did at all, only as a second language. Similarly, though the Hellenic world subscribed in large part to the Orthodox faith, it included pockets of Catholic, Jewish and Muslim Greeks, while of course Orthodoxy itself was shared by other and potentially hostile national and linguistic groups throughout the Balkans.

From the earliest stirrings of the independence movement in all its disparate manifestations, there seems to have been a general agreement that a national identity would have to be forged from the idea of an unbroken historical continuity stretching back to the distant past – above all, to classical antiquity. This was to become an issue of crucial importance to the political and intellectual leadership of the new nation: the Greeks of the 1830s must, they felt, be regarded as the direct lineal descendants of Socrates and Epaminondas as well as, skipping several centuries, of Justinian and the last Palaiologue. There was, of course, no concept then of nationhood as a self-defining cultural phenomenon; if it was worth anything at all, national identity had to be sought in the blood. In the absence of incontrovertible evidence that Kolokotronis and Pericles had ultimately sprung from the same genetic stock, the forgers of national identity, seizing upon Gottfried von Herder’s concept of a linguistic Volk, made the most of the self-evident continuity of the Greek language.

The enormous moral and psychological value of material links with classical antiquity was evident to the more thoughtful of the country’s leaders, as witness the well-known passage in General Makriyannis’ memoirs (1964: 351) in which he describes how he rescued a pair of ancient statues ‘so that they might be of use to the fatherland’. Before even formal ratification of independence by the first Convention of London, Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias had given orders for the foundation of the country’s first archaeological museum (Woodhouse 1973: 429). Some of the earliest Greek archaeologists were in no doubt as to their priorities; Peckham (2001: 117) quotes the unapologetic title of an article published in 1852 by Kyriakos Pittakis, who had been involved in the first restoration of the Acropolis: ‘Material to be used to demonstrate that the inhabitants of Greece are descendants of the Ancient Greeks’.

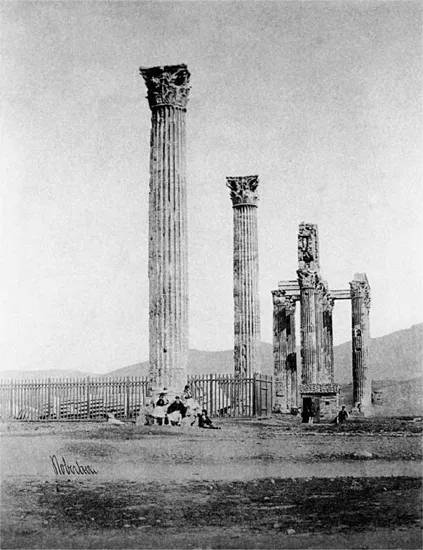

Figure 1.1 James Robertson, Temple of Olympian Zeus from the west, 1853–54

Source: © Benaki Museum Photographic Archive

It was inevitable that the first photographic image taken in Greece should be of the Acropolis of Athens, and just as inevitable that it should be followed by dozens and eventually thousands of closely similar views; once the unique daguerreotype was replaced by the infinitely reproducible albumen print, photographic images became a mass producible and mass consumable item. For both the local market, however restricted it might at first have been, and for the increasing number of foreign visitors, Greece was for a long time synonymous with classical ruins, and classical ruins are what they were offered in profusion by the photographic profession.

In less than a decade, photographs of ruins began to include what were held to be characteristic representatives of the local population (Fig. 1.1). This was partly to provide a useful scale against which to measure the columns, but also in obedience to the dictates of newly fashionable orientalism, which preferred its classicism seasoned with a dash of romance and exoticism – something adequately catered for by extras in white kilts bearing yataghans and long-barrelled muskets. At the same time, their presence was a reminder of the continuity between the original builders and their descendants, a continuity both Hellenes and Philhellenes were happy to emphasise.

Identity crisis

In time, the citizens of the new state, or at least those with the means and leisure to consider such matters, would turn their minds to a consideration of their own identity. Photographic portraiture, increasingly accessible thanks to the professional studios established in perhaps surprising numbers by the mid-1850s, offered a mirror in which the ruling classes could study their reflection and ponder the image they wished to project. High society, under Greece’s first king, Otto of Bavaria, was an uneasy but heady mixture of half-civilised warlords from the mountains, members of the rapidly rising mercantile class, ambitious politicians and optimistic modernisers from all over. The warlords were those lucky, skilful or ruthless enough to emerge from the conflict with a commission in the new national army and a pension, sometimes even a position in court; the modernisers launched into schemes for the establishment of banks or educational institutions, many of which proved successful, including the redoubtable Miss Fanny Hill’s school for young ladies.

Miss Hill being a moderniser, her girls were plainly but neatly clad in sober European dress, but this was by no means the rule. At the pinnacle of society, the king and queen both instituted a policy of cultural cross-dressing, actively encouraging the wearing of Greek national dress at court. A very early group photograph of Queen Amalia’s ladies-in-waiting includes the wives and daughters of Greek notables wearing the authentic local costumes of Psara, Spetses, Hydra and Epirus, as well as two German ladies in European court dress (Fig. 1.2). The seated older woman and the young girl to her left are both wearing examples of an outfit designed for the Queen; based on the dress of Nafpaktos, it became known as the ‘Amalia’ and remained a favourite of fashionable ladies for a number of decades, eventually achieving the status of authentic folk dress.

Figure 1.2 Philibert Perraud, The ladies-in-waiting of Queen Amalia, 1847

Source: © Benaki Museum Photographic Archive

Unsurprisingly, the War of Independence remained the defining event in the lives of those who lived through it. As such, it strongly affected how the participants saw themselves, and the kind of image they wanted to project. We can see this in the relatively large number of portraits from the 1850s and 1860s in which the more politically and socially successful of the war leaders are photographed in variants of the traditional Greek warrior’s costume, including the foustanella or pleated white kilt. These are, of course, highly formalised versions of what the average kleft would have worn in the 1820s, to which they bear the same relationship as do the kilts and sporrans in Raeburn’s paintings to the plaids worn at Culloden; nevertheless, what such portraits testify to is the fact that these men, once powerful military leaders, were now equally influential members of the new order of things.

Inevitably, younger men, or men who perhaps had not fought at all, adopted the same style of self-representation, wearing the foustanella as a mark of national allegiance, or else because it had become, following the example of King Otto, the fashionable thing to be seen and photographed in; just as inevitably, the style did not necessarily flatter the more sedentary individuals. Finally, by the 1870s, what had been a visual signifier of courage and devotion to a national ideal was acquiring overtones of cliché, even of mockery.

The future of Greece, it was becoming clear to all forward-looking men, lay with Western Europe, and sartorially at least, the ruling class conformed within a single generation. We can see the process at work in a wonderfully evocative family group by Margaritis, which shows a grizzled paterfamilias in full evzone regalia, including decorations, while ranged behind him stand his three sons. They are not merely wearing western dress, but three distinct variants of it: on the left, a clean-shaven bohemian lounger in checked pants, three fingers thrust provocatively in his trouser pocket; in the middle, the full-bearded son in sober, buttoned-up black who is clearly destined for the role of hardworking family provider; and on the right, the highly unreliable-looking boulevardier, complete with waxed moustache and cane. Add to the mixture a formidable looking wife and a clearly discontented daughter, and you have the cast of a peculiarly cynical play by Molière.

The royal dynasty inaugurated by Prince Christian William Ferdinand Adolphus George Glücksburg in 1863 felt able to abandon cultural cross-dressing, and to my knowledge there exists no photograph of King George I in a foustanella. This is probably just as well; in the portraits taken by Petros Moraites, now official court photographer, the Georges, father and son, have the aspect of melancholy and rather anxious greyhounds. Only the women of the court remained faithful to the glamour of ‘Greek’ costume, however remote by this time from folk origins. In a group photo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: IMAG(IN)ING THE NATION

- PART II: PHOTOGRAPHIC NARRATIVES, ALTERNATIVE HISTORIES

- PART III: PHOTOGRAPHIC MATTER-REALITIES: PHOTOGRAPHY AS PROPAGANDA

- PART IV: PHOTOGRAPHIC ETHNOGRAPHIES: THE DISPERSAL OF PHOTOGRAPHIC OBJECTS

- AFTERWORD

- Index