![]()

Part I

Historical Background

![]()

1 Islam and Muslims in South Asia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Revolt, Revivalism, and Accommodation

GOOLAM VAHED

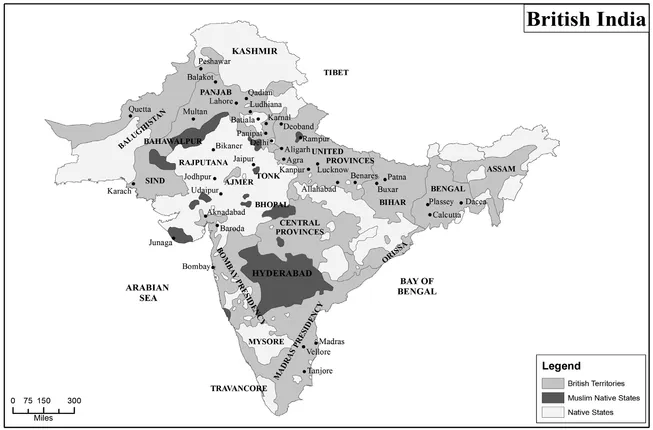

According to the 2011 census, Islam was the second largest religion in India, with Muslims, numbering 172 million, making up 14.2 per cent of the population. The Muslim population of India is the third largest in the world after Indonesia and Pakistan. There are around 180 million Muslims in Pakistan and another 149 million in Bangladesh. Thus, Muslims make up around 40 per cent of the population of this region. Islam came to South Asia (present-day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan and Nepal) in the seventh century through Arab traders who arrived in coastal Malabar and the Konkan-Gujarat. By 711 there was an Arab dynasty under Muhammad bin Qasim in what is now Sindh. The dominant religion in South Asia at the time was Hinduism. There were small pockets of Muslims and for several centuries the two faiths, while totally different in their belief systems and rituals, co-existed. This changed when Muhammad of Ghor (1162-1206) conquered Delhi in 1192. These substantial Muslim conquests were spearheaded by Turks, rather than Arabs, and they established the Delhi sultanate (Kumar, 2010). There were both conflict and cooperation between Muslims and Hindus; Sufis in particular were instrumental in converting to Islam in large numbers among both the warrior and lower castes (Metcalf, 2009: 12).

In the sixteenth century, another Muslim Empire, the Mughal dynasty of Turkic-Mongol origin, was established in India and ruled most of northern India until the mid-eighteenth century. Thereafter its power waned but lingered on until the revolt of 1857. The seven generations of Mughals, starting with Babur (1526-30) and ending with Bahadur Shah II (r. 1837-57), sought to provide centralized administrative, political and military structures, and worked to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state. Akbar (1556-1605) in particular was conciliatory towards Hindus and enlisted them in his armies and government. Aurangzeb (1658-1707), on the other hand, acquired a reputation for political and religious intolerance (see Dalrymple, 2006). By the time that Mughal rule ended, in most parts of South Asia Muslims made up around 15-20 per cent of the population. Hie northwest and northeast were exceptions as Muslims were already in the majority in these regions (Metcalf, 2009: 17).

The Mughals were in decline by the eighteenth century and faced pressure from various regional states, paving the way for British conquest. The English East India Company had been present in South Asia since the early seventeenth century and traded from coastal enclaves like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. From the 1750s the British waged land wars in eastern and south-eastern India and established political power over Bengal. This was due in part to the weakening of the Mughal Empire which created a power vacuum, and in part due to the arrival of French traders. By 1800 the British were busy expanding their control up the Ganges valley to Delhi as well as to the peninsula of southern India. By the mid-nineteenth century the British defeated the remaining opposition and established their dominance after the revolt of 1857 (Ogborn, 2008: 78-111).

The status of Hindu was not in a static and fixed state from time immemorial, Hindu is the Persian name for the river Indus and during the period of Arab rule the whole of the Indian subcontinent was considered 'the land of the Hind' (al-Hind). According to Ernst (1992:23), by the eleventh century, the word Hindu came to refer to all 'inhabitants of India', including Muslims once there were substantial numbers of converts to Islam. Hindu meant Indie in opposition to Turkish newcomers and there was no unified Hindu consciousness at this point. It was only through sustained contact with Muslims over many centuries that Hindu emerged as a distinct religious identity. Hindu and Muslim identities thus must be 'contextualized... identities within the historical processes of migration and a moving frontier' (Sankrityanan, 2006:6). For much of the period until the arrival of the British, Hindus and Muslims lived together, either cooperatively or conflictingly. The conflict aspects were not necessarily being because of their religion per se though that is how the British portrayed it.

For the purposes of this book, this chapter does not examine the historical background of Islam in South Asia or the historiographical debates about the role of Muslims in the region. Rather, it focuses specifically on the state of Muslims and Muslim society during the nineteenth century, around the time that the indentured migrants were making their way to the sugar producing colonies around the globe, and tracks changes in their political, economic and social situation as these transformations often had ramifications in the colonies through transnational contact and exchange of ideas.

Conversion to Islam

There are different interpretations of the entry of Islam into South Asia. Elliot (1871: xxii) argued that the British rescued Hindus from Muslim oppression. He wrote that Hindus were slain for disputing with Muhammadans, of general prohibitions against processions, worship and ablutions, and of other intolerant measures, of idols mutilated, of temples razed, of forcible conversions and marriages...' One example that is frequently cited is that of the mid-eleventh century Sultan Mahmud, head of a Turkish-Afghan kingdom, who is accused of destroying a temple located at Somnath in Gujarat. But historian Romila Thapar (2005) points out that Mahmud was no exception. At the same time as Mahmud was in Gujarat, there was the Hindu Chola Dynasty in south-east India whose conquests extended from the Maldives across the south, with raids as far north as Orissa and eastwards toward Southeast Asia. There were many others, Hindu rajas included, whose exploits were much worse. Another narrative of the Islamic presence in India is that of peaceful accommodation to local practices summed up by terms like "syncretic", "hybrid", or "tolerance"' (Metcalf, 2009: xxi).

Imtiaz Ahmed (1981) argued that Islamic beliefs and practices incorporated local beliefs to produce an 'Indian Islam'. Metcalf (2009: xxii) finds binaries like 'native' and 'Islamic' unsatisfactory and calls for a 'blurring of presumed boundaries. ... Trying to understand the specific ways in which Islamic symbols and institutions work does not make for simple narratives, but, given, the implications of such stories, one ought to welcome narratives that place Muslims in specific contexts, constructing boundaries in different ways at different times'

This is also the point made by a recent collection of articles on Islam in South Asia (Bose, 2015) which seeks out the diverse and different ways in which Muslims live and practice Islam.

Pirs and shrines have traditionally played an important role in the lives of Indian Muslims because Islamization, however, as one defines it, was a lengthy process ... of continuing interaction between the carriers of Islam and the local environment' (Ansari 1992: 13). Pir, a Persian word meaning elder', denotes a spiritual guide among Sufis, also known in other contexts as shaikh, murshid and ustad (Roy, 1996: 1). Large parts of rural India, including the hard to penetrate north-east, were converted to Islam through the efforts of Sufis (ibid.: 104). Metcalf (2009: 8) also emphasizes that 'it is impossible to over emphasise the importance in the subcontinent of Sufis, both culturally and politically' in the early centuries of Islam's presence in South Asia. Rulers patronized them 'as inheritors of charisma (baraka) derived through their "chains of succession" (silsila) from the Prophet himself. Their blessing was regarded as essential to the ruler's power.'

According to Alavi, in many parts of rural India, Muslims believed 'in miracles and powers of saints and pirs, worship at shrines and the dispensing of amulets and charms' (Alavi, 1988: 94). Pirs were Valued because of their capacity to cut through worldly constraints so as to make direct and immediate contact with the divine' (Bayly, 1989: 76-7). Ordinary Muslims regarded pirs as being closer to God than themselves and they were regarded as important intermediaries who could intercede with God on their behalf (Gilmartin, 1988: 41). While the 'Court of God as a cosmological construct seemed to lie beyond the devotee's immediate grasp, the devotee did have a "friend in court", as it were, who represented his interests there' (Eaton, 1984: 61).

In pre-nineteenth century reform India, many Muslims believed that when pirs died they were receptive to intercessory pleas at their burial site (Lawrence, 1982: 30) and from the eleventh century onwards large numbers of Muslims visited local tombs because they believed that praying to God in the presence of a saint was 'much more likely to be efficacious' (Robinson, 1983:189). Richard Eaton has shown that in India, conversion to Islam took place through gradual absorption into shrine cults as the local Hindu population was drawn to the fame of pilgrimage centres and hagiographical accounts of saints' miracles (Eaton, 1984: 338-40). The pir's hospice (khanqah) and tomb (mazar) were thus very important. Metcalf writes that the graves (dargahs) of saints became 'super-charged places of pilgrimage for blessings and intercession' (2009:8). According to Roy, devotees... 'were attracted not only towards the personal and religious charisma and thaumaturgic powers of a living saint but also to such memories of a dead 'saint', perpetuated in his shrine by his followers. ... If the atmosphere of these institutions was emotionally congenial for rural folk, no less attractive were those institutions' capacity and willingness to offer material comforts to the people' (Roy, 1996: 109).

During the Mughal era, the court language was Persian, with the nobility including Persians, Afghans, Turks, and Uzbeks, as well as locally born Hindu Brahmins, Rajputs and Marathas. Audrey Truschke, in her study Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (2016), challenges the idea that the period from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, which was the peak of Muslim rule in India, was marked by religious conflict. She writes (2015):

History, especially during the medieval period of so-called Islamic rule, is often flattened and rewritten in modern India until it bears only the faintest resemblance to any reality of what actually happened. Moreover, the battle over India's past increasingly begins and ends in the present. The truth of any given historical narrative is irrelevant to many, and medieval history is often brazenly altered to reflect modern day political agendas, some of them profoundly troubling. The battle concerning India's Islamic past frequently revolves around the Mughal Empire, the most well-known and certainly the most powerful of precolonial India's many Islamic polities. ... As the Mughals recede further into the past, their valence in debates over India's future is conversely growing.... There is one myth that is perhaps the most pernicious and dangerous: that the Mughals were religiously intolerant and systematically attacked India's Hindu population. This vision of the past is largely derived from the British period when India's colonial masters justified their own atrocities on the subcontinent by supplying India's Hindu majority with an even worse enemy that was supposedly neutralised when India became part of the British Empire. But few people know this history of ideas today. Instead too many have swallowed wholesale the story that the Mughals are the baddies of medieval India who instigated immense Hindu-Muslim conflict.

Truschke (2016) shows that there was a great deal of contact between learned Muslims and Hindus and that rather than being hostile to traditional Indian literature or knowledge systems, the

Source: Metcalf, Islamic Revival in British India, 89.

Mughals supported Indian intellectual ideas. The British benefited from pitting Hindus and Muslims against one another and portrayed themselves as neutral saviours who could keep ancient religious conflicts at bay.' In the post-colonial period, the Hindu right has 'found tremendous political value' in 'erasing Mughal history and writing religious conflict into Indian history where there was none, thereby fuelling and justifying modern religious intolerance'.

Metcalf (2009: 13-16) points out that Mughals continued the patronage of the holy men of the Sufi orders'. Akbar (1556-1605) made regular visits to the shrine of Hazrat Nizam ud-Din Chishti as well as the tomb of his father Humayun. Humayun, in turn, had been a devotee of Muhammad Gwaliori (d. 1562). Jahangir (1605-27) honoured Sufi Milan Mir Qadiri (d. 1635), while his advisors were his disciples. The Taj Mahal, built by Shah Jahan (1627-58) in the tomb of his wife Mumtaz, presented the emperor as the equivalent of the Divine. While Aurangzeb (1658-1707) displayed personal piety, in general, Metcalf (2009: 14) observes that the Mughals

stand in contrast to the Ottomans in their lack of engagement with the ulama. The emperors' Islamic legitimacy derived more from their own charismatic image, their links to holy men, and their patronage of mosques, gardens, and sarais, as well as dargahs of the Sufis All the emperors extended patronage to Islamic thinkers, holy men, and sites, even as, in their capacity as rulers of culturally plural politics, they also patronized the religious specialists and places of worship of non-Muslims.

Moin's (2014: 1-3) innovative study brings together scholarship on sacred kingship and sainthood in Islam by arguing that early Mughal monarchs had a style of leadership 'that was "saintly" and "messianic" . ., based upon Sufi and millennial motifs'. The Mughal emperor was seen as the prophesized messiah who would guide the flock to a new millennium era of peace and justice. Akbar was the classic example of a 'spiritual guide and material lord' as he established 'a lasting empire of unrivalled grandeur and also fashioned himself as the spiritual guide of all his subjects regardless of caste or creed'. 'Mystics and monarchs', Moin writes, were 'competitors and collaborators' (Moin, 2014: 7). This points to the importance of Sufis in Indian Muslim life.

In addition to pirs and dargahs, public festivals such as Muharram were also an integral part of Indian Islam. It was a festival in which both Muslims and Hindus participated, while Hindus also visited Muslim shrines. Muharram is discussed in Chapter 9.

The eighteenth century, which witnessed the decline of the Mughals and the ascendancy of the British, saw rapid population growth and urbanization. In this context there was renewed emphasis on Chishti Sufism, particularly in Punjab and Afghanistan; Lucknow's Shi'a rulers built massive structures such as imambaras for Muharram rituals and this period also saw the emergence of the reformist scholar Shah Waliullah (1703-62) who had studied with hadith scholars in the Hijaz (present-day Saudi Arabia), and tried to end conflict amon...