eBook - ePub

Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability

Principles and Practice

- 278 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book offers conceptual and practical insights into the complex interactions between ecotourism and the natural environment, with consideration given to government policy, marketing by suppliers, consumer behaviour and visitor/environmental management. Illustrated by international case studies the roles of and interplay between tour operators, their clients, resource managers and local communities are examined. This creates a comprehensive and insightful overview of the factors that work for and against the achievement of environmental sustainability in and through ecotourism. The result is a critical examination of ecotourism and environmental sustainability that highlights ideas for best practice and proposes new directions for future research

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability by Tim Gale, Jennifer Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Context of Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability

Chapter 1

Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability: An Introduction

Tim Gale and Jennifer Hill

Ecotourism: Its Meaning and Significance

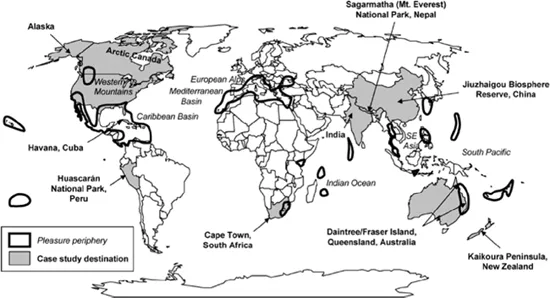

Thanks to the creation of previously inaccessible and undeveloped destinations, and a preference for independent and special interest holidays in non-resort locations, there is little left of the natural world that has not been exploited or commoditized for tourist consumption. The extension of the so-called ‘pleasure periphery’ (after Turner and Ash 1975; see Figure 1.1) into ever more remote and exotic areas has been driven to a significant degree by various forms of nature-based tourism, especially ecotourism, which are manifest in a range of environments from polar to tropical and terrestrial to aquatic, and which exhibit a strong correlation with periphernortal and (predominantly public) protected areas. Nature-based tourism in general is one of the fastest growing sectors within the global tourism industry (Buckley 2000, Ryan et al. 2000, Wight 2001, Kuo 2002), it being defined as tourism ‘primarily concerned with the direct enjoyment of some relatively undisturbed phenomenon of nature’ (Valentine 1992: 108). Market estimates are hard to come by, given the lack of consensus over the use of the term(s), but it was suggested in 2004 that eco-/nature tourism was growing three times faster globally than the tourism industry as a whole (WTO 2004, cited in TIES 2006). Reasons for this growth include demographic changes in source countries (such as older populations and, in turn, the growing number of more experienced travellers), ‘beach boredom’ as a symptom of a maturing market for 3S (sun, sea, sand) holidays and increasing environmental awareness on the part of the general public (Ayala 1996). It is also attributable to the rapid development of an industry comprised of specialized (for example ecolodges, ecotour operators, and suppliers of transport services and infrastructures within a given ecotourism destination) and non-specialized businesses (such as hotel chains, airline and cruise ship operations, and retail travel agents), ranging from small- and medium-sized enterprises to transnational corporations (Weaver and Lawton 2007).

Under the broad banner of nature-based tourism, ecotourism has been suggested as a way in which increasing numbers of visitors seeking an intrinsically environmental tourism experience can be accommodated, whilst minimizing the costs and enhancing the benefits associated with natural area tourism (Boo 1990, Cater and Lowman 1994). Many definitions and types of ecotourism exist (Orams 2001, Donohoe and Needham 2006) but, in its broadest sense, it concerns travel to a natural area; involving local people; feeding economic profit into local environmental protection; and contributing to the maintenance of the local environment and species diversity through minimizing visitor impact and promoting tourist education (Valentine 1993, Western 1993, Ceballos-Lascuráin 1998, Diamantis 1999, Fennell 2001, 2003). In this way, ecotourism (as a subset of alternative tourism) is being promoted by governments and the tourism industry as a sustainable alternative to mass tourism. However, critics have suggested that ecotourism can be damaging to the natural environment, not least with respect to the environmental cost of air travel to popular destinations and the potential for unwittingly disturbing soils and ecosystems through accommodation and activities on site (Wheeller 1991, 1993, Hjalager 1996, Conservation International 1999, Wearing and Neil 1999, Kruger 2005). Doubts have also been raised about the ‘true’ motivations of ecotourists, which appear to have as much to do with sustaining the ego as the environment (Wheeller 1993), and the sense in which ecotourism encourages increased use of natural areas and greater penetration into sensitive environments, thereby putting the very future of indigenous tourism industries at risk (Mihalic 2000). There is a tendency to overstate its significance, too, when in fact it constitutes only a small proportion of global tourism (estimated at between 2 per cent and 4 per cent; WTO 2002, cited in Cater 2004).

Figure 1.1 Location of the ‘pleasure periphery’, and of destinations and destination regions that feature as case studies in this book

Source: Adapted from Weaver (1998: 48)

Before we explain the aim, philosophy and structure of this book, it is perhaps useful to provide a brief introduction to definitions of ecotourism; ecotourist types and motivations; and ecotourism’s (environmental) sustainability credentials. With regards to the first consideration, Fennell’s (2001) content analysis of ecotourism definitions identifies no less than 85 of these in the literature available at that time which, for a term that only entered academic discourse in the late 1980s, is quite remarkable (if not a little counter-productive). Definitions of ecotourism leave much to the interpretation of the reader, but they more or less cohere around three criteria, namely that ‘(1) attractions should be predominantly nature-based, (2) visitor interactions with those attractions should be focused on learning or education, and (3) experience and product management should follow principles and practices associated with ecological, socio-cultural and economic sustainability’ (Weaver and Lawton 2007: 170). However, given the existence of something that approximates to an ecotourism experience in modified settings such as botanic gardens (see Chapter 12), not to mention the ‘accidental ecotourist’ and the potential for behaviour associated with states of mindlessness as well as mindfulness (after Moscardo 1996, 1999), plus an emerging critique of earlier work which problematizes ecotourism’s role in sustainable development and environmental conservation (for example Butcher 2005, Kruger 2005, Cusack and Dixon 2006, Southgate 2006), one has to accept that there is no definition available that satisfactorily explains this phenomenon of contemporary (postmodern) society. That said, the distinction may usefully be made here between positive (i.e. what is) and normative (i.e. what should be) ecotourism definitions; whereas a universal definition that everyone can subscribe to remains a distant prospect (and, arguably, a futile project), there is an emerging consensus over the inclusion of certain ‘value-based dimensions’ such as conservation, community involvement and social responsibility (Weaver and Lawton, 2007: 1169). This is also apparent in Garrod’s (2003) Delphi study, which indicates a preference amongst experts for prescriptive, rather than descriptive, definitions of ecotourism (as well as summarizing the reasons why they can be useful).

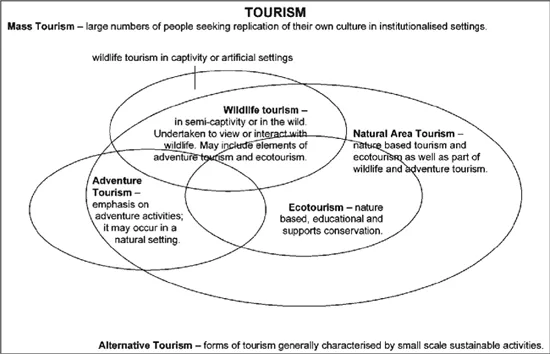

Figure 1.2 Relationship of ecotourism to other forms of tourism

Figure 1.2 illustrates the relationship between ecotourism and other forms of tourism. This follows the typology of Newsome et al. (2002) in which ecotourism is seen entirely as a subset of natural area tourism, incorporating elements of wildlife and adventure tourism as acknowledged by a number of researchers (for example Page and Dowling 2002, Fennell 2003). It accommodates Fennell’s (2003: 16) belief ‘that ecotourism is distinct from mass tourism and various other forms of AT [alternative tourism]’, whilst acknowledging the common ground between them (see Weaver 2005 on mass ecotourism, and Fennell 2003 on the difficulty of distinguishing between adventure tourism, cultural tourism and ecotourism in similar environmental settings). However, by its inclusion we are not asserting that this is the only way of seeing ecotourism in the context of other tourism types (see Weaver 2001 for alternative illustrations).

Moving on to the second of the above-mentioned considerations, namely ecotourists and their motivations, empirical research has shown that those who have participated in some form of nature-based tourism (which qualifies them as ‘ecotourists’ in a number of published studies) tend to be slightly older (between 35 and 54 in particular), better educated and more affluent (and, therefore, prepared to pay more for their holidays) than those who do not participate (see Wilson and Garrod 2003 for a summary of demographic and other characteristics). Furthermore, they are likely to stay longer and be more tolerant of basic conditions than general travellers. Environmental awareness and respect for local customs and culture are also differentiating features, as is gender (at least for certain activities such as bird watching, which attracts more males than females). However, despite having much in common, there are many different types of eco-/nature tourist that are distinguishable by factors including level of organisation (such as do-it-yourself ecotourists, ecotourists on tours and school or scientific groups, as identified by Kusler 1991) and dedication to nature (for example Lindberg’s 1991 typology, comprising hard-core, dedicated, mainstream and casual nature tourists). Similarly, the degree of difficulty and level of engagement are used by Laarman and Durst (1987) in arguing for the distinction between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ ecotourism experiences.

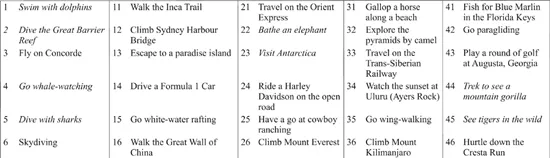

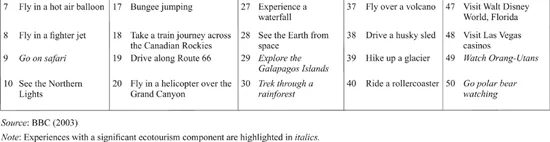

The most common reasons offered by ecotourists for undertaking a given trip are a desire to enjoy scenery and nature, and to encounter new places and experiences (see Chapters 9 and 11), with the imperative to ‘get away from it all’ of less importance to the ecotourist than, say, the adventure tourist. Motivations can and do vary by market, however, as summarized by Wight (2001). Suffice to say, for an explanation as to what motivates the ecotourist, one sometimes has to look beyond the academic literature. For example, in the first quarter of 2003 the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) conducted a survey of visitors to its website that attempted to establish the ‘50 things to do before you die’, the results of which were subsequently broadcast on the BBC’s Holiday programme (Table 1.1). Not surprisingly, long-distance travel features in nearly all of these ‘must-do’ activities. What is more pertinent, however, is that a large number correlate with a wildlife or adventure tourism experience, most likely with a significant ecotourism component. Examples include, but are not confined to: swimming with dolphins (1); going on safari (9); seeing elephants in the wild (22); exploring the Galapagos Islands (29); trekking through a rainforest (30); and watching mountain gorillas (44). Crucially, these activities remind us of the potential for ecotourism (and related forms of tourism) to deliver what Maslow, writing in the 1950s, described as a ‘peak experience’. In turn, they are able to address higher order human needs, especially self-actualization and transcendence (personal growth and fulfilment, and helping others to self-actualize). Indeed, opportunities to develop knowledge and understanding in beautiful surroundings (and, therefore, to satisfy cognitive and aesthetic needs as a pre-condition for self-actualization) are present in most, if not all, ecotourism encounters. Hence, we can conclude that ecotourists are motivated by so-called ‘growth motivators’ (and not just ‘deficiency motivators’, such as physiological, security, belongingness/love and esteem needs), and that ecotourism can help them to achieve their full potential (see Maslow 1987 for an explanation of these terms).

Table 1.1 ‘50 things to do before you die’

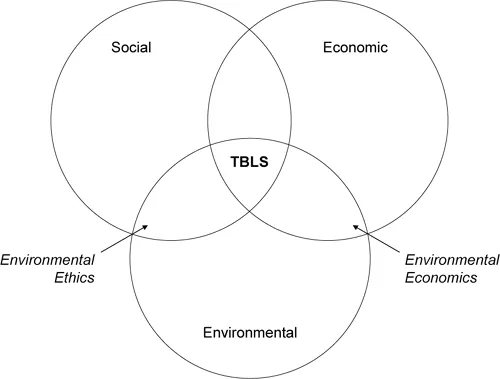

Figure 1.3 Elements of triple-bottom-line-sustainability (TBLS)

Finally, there is the issue of ecotourism and environmental sustainability (the latter being one of the components comprising the ‘triple-bottom-line’) (see Figure 1.3). Broadly speaking, ecotourism is linked to the emergence of ‘new tourism’ and associated production practices and consumption patterns (see Poon 1993); it is one of four key types identified by Shaw and Williams (2004: 119), the others being heritage/cultural tourism, adventure tourism, and visiting theme parks/mega-shopping malls (see also Mowforth and Munt 2003: 93 for an extended typology/glossary of terms). Although contested, it is suggested that some of these new forms of tourism are based around sustainable ideas (such as environmental stewardship, inter-generational and intra-generational equity). Certainly, we are told that ecotourism is small in scale, non-consumptive, ethical/responsible, and of benefit to local people. It is also thought to encourage pro-environmental behaviours (both home and away), when accompanied by interpretation (see Chapter 11).

This was the thinking behind the International Year of Ecotourism, in 2002 (as proclaimed by the United Nations). However, in the absence of an appropriate management regime, where ‘those who initiate and develop ecotourism … operate within the capacity of the environment to absorb the impacts’ (Wilson and Garrod 2003: 4), ecotourism is unlikely to be sustainable ecologically by any relevant measure. There is also the possibility that ecotourists (however well intentioned) might disturb the feeding and breeding patterns of wildlife, transmit diseases and modify habitats, just by being present in environmentally sensitive areas. In addition, a great many tourism products labelled with the prefix ‘eco-’ have few, if any, of the above characteristics (see Chapter 13), which suggests that ‘ecotourism is being used [primarily] to meet economic objectives by promoting the quality of the environment to attract international tourists’ (Holden 2005: 130), and not for the specific purpose of natural resource conservation (a minority of cases excepted). Finally, given that most ecotourism destinations are geographically remote in relation to the markets they serve, there is the issue of carbon expenditures associated with long-distance travel and their contribution to climate change (see Chapters 2 and 3). Clearly, then, ecotourism is not (and can never be) synonymous with environmental sustainability, contrary to what some advocates would have us believe.

The Ecotourism Body of Knowledge

Despite the title of this section, it is not our intention here to review comprehensively the literature on ecotourism, especially as some excellent reviews exist already (see Weaver and Lawton 2007, referenced throughout this opening chapter). Instead, we direct readers to the following:

• The ever-expanding range of introductory textbooks, which deal at length with the origins and concepts of ecotourism; where it lies within broader tourism types; its economic, environmental/ecological and socio-cultural impacts; the planning and management of ecotourism businesses; and ecotourism organizations and policies (see, for example, Wearing and Neil 1999, Page and Dowling 2002, Fennell 2003, Weaver 2008).

• More specialized publications that focus on certain aspects such as policy and planning (Fennell and Dowling 2003); underlying environmental ideologies linked to politics of north–south relations and social justice (Duffy 2002, Butcher 2007); and economic and sustainable development in less developed countries (Weaver 1998, Honey 1999).

• The 500-plus articles of relevance in refereed journals, accessible via academic databases and search engines using appropriate keywords such as ‘ecotourism’, ‘ecotourist’ and so on (including those published in the dedicated Journal of Ecotourism, established in 2002).

In their review of the ecotourism literature, Weaver and Lawton (2007) identify three ‘macro-themes’ that may help contextualize the contents and approach of this book. Firstly, they note that the subject has been transformed over the past decade due to processes of de-differentiation (the blurring of the boundaries between ecotourism and other forms of tourism, as exemplified by upscale ecolodges and recreational hunting and fishing in protected areas) and segmentation (such as the emergence of whale watching and Antarctic tourism as sub-fields of enquiry). Secondly, they record ongoing efforts to make sense of ecotourism impacts, which...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- The Context of Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability

- Thematic Case Studies

- The Future for Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability

- Index