![]()

1

Introduction

This book is a study of a single image – though arguably one of the best known that has come down to us from seventeenth-century science. This is the plate that was published as the frontispiece to Thomas Sprat’s History of the Royal Society of London (1667). It was designed by the virtuoso and diarist, John Evelyn, and etched by Wenceslaus Hollar, the Bohemian artist long domiciled in England.1 Within an architectural setting surmounted by the Royal Society’s coat of arms and festooned with scientifically significant books and objects, it shows a bust of King Charles II, the society’s founder and patron, placed on a pedestal and being crowned with a wreath by the goddess Fame. The column on which Charles’s bust stands is flanked to the right by the society’s first President, William, Viscount Brouncker, and to the left by Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, the figure from the early seventeenth century who more than anyone else was the society’s intellectual inspiration. Bacon provided a mandate for the complete reformulation of knowledge about the natural world, not least through the collection of a great inductive ‘natural history’, and he also emphasised the desirability of the application of science to practical use. Here, he is shown in his robes as Lord Chancellor.

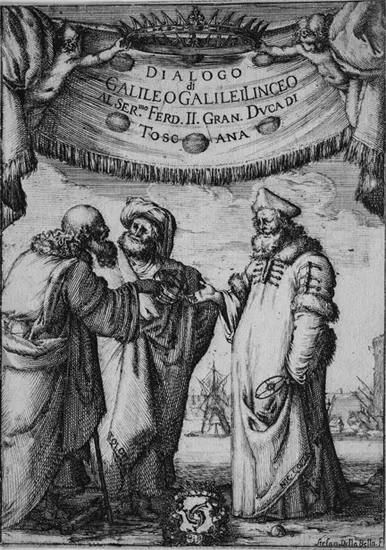

In seeking to encapsulate the message of a book in a prefatory image, the print that precedes Sprat’s History falls into a tradition of providing frontis-pieces and engraved title-pages that by the late seventeenth century was well established both in Britain and in Europe more generally.2 Indeed, the use of such plates to celebrate and legitimise the ‘new’ science of the period has recently begun to attract attention from historians.3 In the words of the Jesuit astronomer, Christoph Scheiner, ‘a small image teaches what many written words cannot say,’ and this was a point that was not lost on authors like Galileo, whose works were embellished with striking illustrations, as with the title-page that Stefano Della Bella designed for the Dialogue concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which powerfully evokes the message of Galileo’s book (Fig. 1.1).4

Indeed, through such images, astronomers like Tycho Brahe and Andrea Argoli sought to establish their lineage from Atlas and Hercules and to raise the status of their discipline accordingly, while a succession of authors used

Figure 1.1 Stefano Della Bella’s etched title-page for Galileo’s Dialogue concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), showing Aristotle, Ptolemy and Copernicus.

elaborate designs – often including personifications based on biblical and classical imagery – as a means to dignify the pursuits in which they were engaged. By comparison, the Sprat frontispiece might seem rather artful and understated in the way in which it puts across its message, but it has nevertheless been reproduced very frequently. This is largely because it is the most striking image relating to the early Royal Society that we have, encapsulating the society’s ethos in significant ways that will be explored in the course of this study.5 Indeed, no book on the early Royal Society and its context seems complete without a reproduction of it.

It is also worth noting the context of Sprat’s History of the Royal Society itself in terms of self-promoting publications by the new institutions devoted to natural philosophy of which the Royal Society was one. Thus the Accademia del Cimento, founded under the auspices of the Medici family at Florence in 1657, brought out a volume of Saggi di Naturali Esperienze which, though not actually published until 1667, had been in preparation since the start of the decade.6 Equally notable were the publications of the Académie des Sciences founded in Paris in 1666, including the grandiose volumes devoted to L’Histoire des Animaux, originally published in 1671, and L’Histoire des Plantes, published in 1676, elephant folios that were distributed under the auspices of the French monarchy.7 Both the volumes just mentioned feature lavish etchings by Sébastien Leclerc which provide a profuse pictorial record of the academy’s members and patrons, and of its apparatus, activities and milieu (Figs. 1.2, 5.21).8 We entirely lack an English equivalent to this mouth-watering visual resource, and it is perhaps partly for this reason that the Evelyn/Hollar image has come to acquire such prominence in relation to the seventeenth-century Royal Society.

Nevertheless, there are many questions to be asked about it and how it came into being. Was it an original composition by Evelyn, or is it based on earlier exemplars? Can one identify all the instruments, books and other objects that appear in it, and what significance should be attached to their inclusion? Perhaps above all, how did the plate come to be designed in the first place, and what is its true relationship with Sprat’s book? The latter question is a pressing one, since the status of the print in relation to the volume is problematic. Facing the title-page of the book, on the verso of the half-title, is a depiction of the society’s coat of arms (see Fig. 2.1); in copies of the book in which the etched image is to be found, it is often inserted rather uncomfortably between that and the title-page. In addition, many copies of the book lack the Evelyn/Hollar plate, although these are often in contemporary bindings and there is no sign that it has been removed. In any case, the print is larger in size than the format of normal copies of the book, which means that, insofar as it appears in these, it has had to be cropped or folded to make it fit. It is of just about an appropriate size for the choice copies of the book that were printed on large paper, and it has sometimes been claimed that it must have been produced for inclusion in these: but this seems to be a retrospective rationalisation.9 Instead, there is a clear reason for the

Figure 1.2 Sébastien Leclerc’s etching of Louis XIV’s (imagined) visit to the Académie des Sciences in Paris, from Mémoires pour Servir à l’Histoire Naturelle des Animaux (1671).

anomalous status of the plate, which was first divulged in 1981 and will be recapitulated here. This is that it was not originally intended for Sprat’s work at all. In fact, it was designed for a completely different book, a defence of the Royal Society devised by the Somerset virtuoso, John Beale, and it was re-routed to Sprat’s volume only when Beale’s project proved abortive.10

This book will therefore begin by giving an account of Beale’s scheme and its context, prior to providing a full analysis of Evelyn’s image in its Royal Society setting. This will comprise three parts. First, we will consider the overall iconography of the image and its – in some respects surprising – message concerning Evelyn’s conception of the society’s role. We will then examine the myriad of details included in the plate and their significance, looking first particularly at the portraits and books included in it and the trappings of the society’s institutional status. A further chapter will then give minute attention to the various instruments that are depicted. Such scrutiny of the print’s details raises questions about its design process, including the relative contribution of designer and etcher, and these are addressed in the context of seventeenth-century print production more generally. In a final chapter, we will consider the print’s history after its publication, including the extent to which Evelyn seems to have used copies of it to exemplify the combination of technological and artistic accomplishment to which he believed the Royal Society should aspire.

Notes