eBook - ePub

Visualizing Research

A Guide to the Research Process in Art and Design

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Visualizing Research guides postgraduate students in art and design through the development and implementation of a research project, using the metaphor of a 'journey of exploration'. For use with a formal programme of study, from masters to doctoral level, the book derives from the creative relationship between research, practice and teaching in art and design. It extends generic research processes into practice-based approaches more relevant to artists and designers, introducing wherever possible visual, interactive and collaborative methods. The Introduction and Chapter 1 'Planning the Journey' define the concept and value of 'practice-based' formal research, tracking the debate around its development and explaining key concepts and terminology. 'Mapping the Terrain' then describes methods of contextualizing research in art and design (the contextual review, using reference material); 'Locating Your Position' and 'Crossing the Terrain' guide the reader through the stages of identifying an appropriate research question and methodological approach, writing the proposal and managing research information. Methods of evaluation and analysis are explored, and of strategies for reporting and communicating research findings are suggested. Appendices and a glossary are also included. Visualizing Research draws on the experience of researchers in different contexts and includes case studies of real projects. Although written primarily for postgraduate students, research supervisors, managers and academic staff in art and design and related areas, such as architecture and media studies, will find this a valuable research reference. An accompanying website www.visualizingresearch.info includes multimedia and other resources that complement the book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visualizing Research by Carole Gray,Julian Malins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Architecture General1 Planning the journey: introduction to research in Art and Design

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

1.1 Travellers’ tales: how do practitioners come to do research?

1.2 The Research Process – What? Why? How? So what?

1.3 A Route Map: the importance of methodology

1.4 The ‘Reflective Practitioner’

1.5 Completed research for higher degrees: methodological approaches

1.1 TRAVELLERS’ TALES: HOW DO PRACTITIONERS COME TO DO RESEARCH?

Socrates asked questions, Aesop told stories. In learning contexts, the use of Socratic dialogue involves the teacher asking questions that the student tries to answer. In Aesopic dialogue (Ferguson et al., 1992) the student asks questions and the teacher answers with stories. Stories are a powerful and memorable means of making sense of the world and engaging imaginatively in learning. Our question then – ‘How do practitioners come to do research?’ – will be addressed by a number of stories from practitioners who have been through the process of research for higher degrees.

The Artist’s tale

‘After graduating from a traditional, studio-based BA Honours degree, I maintained an individual studio-based model of visual art practice. I undertook a collaborative Public Art commission with a fellow artist and found the experience enabled us to work on a larger scale, in a non-art context, and to produce work that we would not have conceived individually, and which combined both our ideas and skills. I continued learning about Public Art by contributing to project administration, fundraising, and manufacturing work through a Public Art organization. These experiences helped to focus my questions about the roles and functions of art and artists contributing to social and cultural development.

I undertook postgraduate study in Exhibition Interpretation, this experience of education contrasted with my art college experience, as it was more interdisciplinary and collaborative. I began to recognize the particular strengths and weaknesses of the existing educational model for visual artists and began a personal quest to find new routes for visual artists and new models of practice.

These questions provided an opportunity to re-think the nature of art practice both pragmatically and philosophically. I developed a proposal for an alternative arts venue with the aim of encouraging, supporting and facilitating experimental interdisciplinary projects between artists and other professionals. To investigate further the practicalities of developing an interdisciplinary and collaborative model of art practice, and to address the implications of this challenge to individual “authorship”, I undertook a practice-based PhD.’

The Designer-maker’s tale

‘After finishing my degree at art school I set up my own business making and selling ceramics in a rural studio/workshop. After several years I returned to full-time education to complete a Masters degree. My particular interest was in using firing techniques that, whilst producing what I hoped was visually exciting glazes, had a tendency to be environmentally unfriendly. Wishing to continue to produce interesting work without falling out with my neighbours or damaging my health in the process, led me on a quest for alternative techniques that would not be harmful to the environment or people. When an opportunity arose to undertake a PhD project that had similar objectives to my own I applied immediately. As the research progressed, the study became increasingly focused and I began to realize that my original aims had been overambitious. Coming from a non-scientific background led to some significant challenges, especially when it came to thinking about methodology. The research provided some contributions to knowledge in the field of ceramics but for me the real significance of the PhD lay in the questions it raised regarding what might be appropriate research methodologies for artists and designers.’

The Undergraduate’s tale

‘On completion of the third year of my undergraduate degree in product design, I was presented with a Vacation Award that provided the finance for me to investigate environmentally friendly design for three weeks in Oslo, Norway. Unaware of what constituted research, I dived right in and began planning my trip. I organized a series of interviews and visits with individuals and institutions in the hope that they would hold the answer to my questions: what is environmentally friendly design? How can it be achieved? The experience of exploring and discussing these questions was both exciting and nerve wracking. It took me out of my comfort zone of designing and I realized I had an interest in research. On completion of my undergraduate degree I looked around for an opportunity that would allow me to explore my interest in both research and environmentally friendly design. The PhD was that opportunity. It has been a great learning experience – I find I am able to do things I never thought I would do, for example present a paper at an international conference. There have been many high and low points throughout the study. I’ve had to put a lot into it, but feel I have got a lot in return. The PhD has certainly been a challenge!’

The Lecturer’s tale

‘I’d been teaching in art college for a couple of years – working mainly from intuition based on my experience as a young practising artist about what students needed to learn and how. Having had no formal teaching education, I began to wonder if I was doing this right – nobody else seemed to know – were there things I needed to learn? Out of curiosity I became involved in a series of seminars at the local university about higher education, involving a range of lecturers from other disciplines. As we discussed approaches to teaching and learning it became pretty obvious that I was a different kind of beast! At almost every point I had to declare ‘we don’t do it like that in Art and Design!’. In the end they got so fed up with me saying this that they challenged me to explain more clearly what exactly we did do. Of course I didn’t know enough about teaching and learning in art and design to answer them properly, but the gauntlet was thrown down and I had to do some serious research. But I didn’t know what that was either! The whole thing was a mystery, but I decided there was no way back. I embarked on a PhD armed only with my experience of practice and determined to bring to the research a creative and visual approach, even though I was doing “educational research”. In the end, the PhD research turned out to be a difficult but life changing experience. By the way, what I discovered about teaching and learning was much less significant than the experience of doing the research, and since then I’ve never stopped being a researcher.’

From these stories we can see that, typically, the experience of being a practitioner, or teaching and learning about practice, raises important questions, and in some cases, provokes challenges to the actual survival of the practitioner. In reflecting critically on practice we ‘begin to wonder’, to sense that things could be different, better – ‘new routes’, ‘new models’, ‘alternative technologies’. We are challenged by others to ‘explain more clearly’ or to be more environmentally friendly.

Where most angels fear to tread, we embark upon a ‘quest’, seize opportunities to ‘explore’, leap into the unknown and ‘dive right in’. We find ourselves engaged in in-depth study where we must revisit our assumptions and focus our questions. The experience is simultaneously ‘exciting and nerve wracking’ presenting ‘significant challenges’ that take us out of our ‘comfort zone’. If we are tenacious and persevere we reach another level – ‘able to do things I thought I never would do’, as one of our contributors says. Research can be a ‘life changing experience’ – hopefully a positive one – through which we can become more critical, reflective and creative practitioners.

Reflection and action: suggestions

• How have you come to the decision to do research? What are your motives? Write a short story about it.

• What do you hope to gain by undertaking research? Include this at the end of your story.

1.2 THE RESEARCH PROCESS – WHAT? WHY? HOW? SO WHAT?

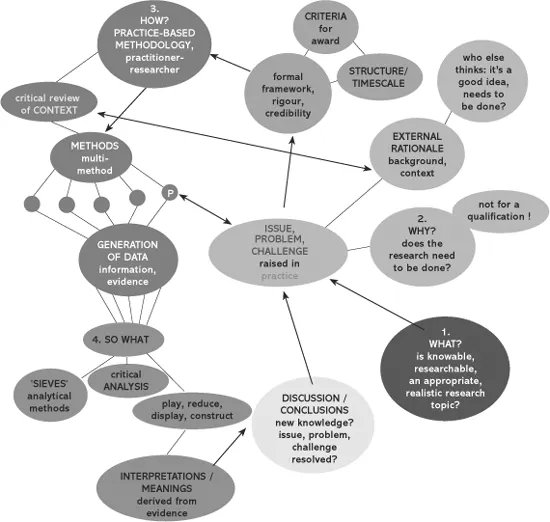

Research is a process of accessible disciplined inquiry. The process described here is essentially generic but should be framed and customized by your particular discipline and subject area. The process is usually shaped by three apparently simple questions:

• ‘what?’ – the identification of a ‘hunch’ or tentative research proposition, leading eventually to a defined and viable research question

• ‘why?’ – the need for your research in relation to the wider context, in order to test out the value of your proposition, locate your research position, and explore a range of research strategies

• ‘how?’ – the importance of developing an appropriate methodology and specific methods for gathering and generating information relevant to your research question, and evaluating, analysing and interpreting research evidence.

A fourth question – the provocative ‘so what?’ – challenges you to think about the significance and value of your research contribution, not only to your practice but to the wider research context, and how this is best communicated and disseminated.

Although the stages are presented here in a numbered sequence for clarity’s sake (Figure 1.1), in reality they are part of a continuous iterative cycle, or helix, of experience (consistent with Kolb’s 1984, ‘experiential learning cycle’). Stages can be revisited several times, and usually some are concurrent with others, for example, reflection, evaluation and analysis are ongoing activities at every stage (see Orna and Stevens, 1995, chapter 1, pp. 9–12). Be prepared to be flexible and responsive to your research situation. Each stage in this overview is expanded upon in subsequent chapters.

Key stages of the process

What might you research?

Stage 1. We have seen from the ‘travellers’ tales’ that ideas for research can emerge from a vague but nagging hunch, a personal dissatisfaction, or some other issue within creative practices identified by the practitioner. Alternatively, there may be a professional stimulus to which the practitioner must respond creatively in order to survive and thrive, for example new approaches to practice in response to cultural, social economic, or environmental challenges. Whatever the initial impetus, the ‘what’ should come from a genuine desire to find something out, or else it is unlikely that the study or the enthusiasm for it will be sustained.

Why is your research needed?

Stage 2. You should consider whether your idea really could be developed into a viable research topic that needs researching. Usually there is a good personal reason for undertaking the research – especially issues relating to practice – but is there a wider need and can this be confirmed?

Stage 3. You will need to make an initial search for information that supports your hunch (research proposition) and ideally suggests that research is required. It is important to get some feedback on this from your peers and others in professional and research contexts. Gather some background information on your research proposition and its ethical implications.

Stage 4. If there is no apparent external rationale for the research then it could be considered too much of an indulgent and idiosyncratic idea for a research project. You could stop now!

Stage 5. More positively, you could refocus your initial proposal in response to what you have so far discovered. You may have identified research that is similar, or even identical, to what you are proposing. In this case there is no point in reinventing the wheel! The chances are that this completed research has raised new questions to be answered. This gives you a real opportunity and a firm basis from which to develop your own particular research proposal.

Figure 1.1 The Research Process – important issues to be considered at the start of the research

These preliminary stages are extremely important in ‘planning your journey’ and beginning to identify and formulate a research question and a suitable research strategy (this is covered in detail in Chapter 3 – Locating Your Position). In ‘planning the journey’ it is crucial to have some idea of where you want to go and why. Also, you should take advantage of the knowledge of explorers who have visited similar areas. Research is a journey of exploration through which individuals can make small but significant contributions to understanding the landscape of research in Art and Design.

The next stages in the research process usually involve finding already completed research in the public domain, and using this knowledge to help situate yourself as a researcher and focus your research question. In traditional research terms, this kind of survey and evaluation would be called a ‘literature review’. Increasingly, information exists in a wide range ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- Authors’ biographies

- By way of a foreword: ‘Alice is in wonderland’. Discuss

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Planning the journey: introduction to research in Art and Design

- 2 Mapping the terrain: methods of contextualizing research

- 3 Locating your position: orienting and situating research

- 4 Crossing the terrain: establishing appropriate research methodologies

- 5 Interpreting the map: methods of evaluation and analysis

- 6 Recounting the journey: recognizing new knowledge and communicating research findings

- Appendix 1 Taxonomy of assessment domains

- Appendix 2 Criteria for assessing PhD work

- Appendix 3 What does it mean to be ‘original’?

- Appendix 4 Postgraduate portfolio of evidence (using taxonomy of assessment domains)

- Glossary: research terms relevant to the Art and Design context

- Index