- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Climate change is arguably the most important environmental issue that the world currently faces. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) offers the possibility of significant reductions in the volume of CO2 released into the atmosphere in the near to medium term. As a fairly new technology that has not been widely adopted, there remain some uncertainties related to both viability and desirability. This book discusses the key issues with regard to technical and legal feasibility, economic viability and public and stakeholder perceptions. It also provides recommendations for policy and future research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Carbon Capture and its Storage by Clair Gough, Simon Shackley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 The Climate Change Problem and the Potential Role of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage

It is now widely recognised that large scale reductions in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are required during this century in order to limit the extent of climate change modification. Anthropogenic CO2 emissions are largely a result of burning fossil fuels (constituting 80 per cent of such emissions). Once in the atmosphere, CO2 acts as a greenhouse gas, causing: mean global temperatures and sea levels to rise; precipitation patterns to change; the frequency and severity of extreme weather events to be potentially enhanced; and the acidification of the oceans – with widespread implications for global support systems which underpin existing human activities (IPCC 2001 and 2001a; Schellnhuber et al. 2006). Fossil fuel combustion currently accounts for annual emissions into the Earth’s atmosphere of about 23 x 109 tonnes CO2 (or 23 Giga tonnes, Gt). This represents a global increase in anthropogenic CO2 emissions of 70 per cent between 1971 and 2002 (IEA 2004).

Various scenarios have been prepared to explore how anthropogenic CO2 emissions might change over the next few decades to the end of the twenty-first century. The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook (WEO) Reference Scenario (IEA, 2004 and 2004a) predicts that a 1.7 per cent per year increase in CO2 emissions between 2000 and 2030 (a similar growth rate to that observed over the past 30 years) would result in a further 63 per cent increase in CO2 emissions from today’s level. This assumes that fossil fuel combustion remains the dominant energy source, accounting for more than 90 per cent of the increase in energy use over this period. Even under the World Alternative Policy Scenario, which includes CO2 reduction measures and a reduced reliance on fossil fuels, the IEA’s WEO analysis suggests a 40 per cent increase in global CO2 emissions from today’s level.

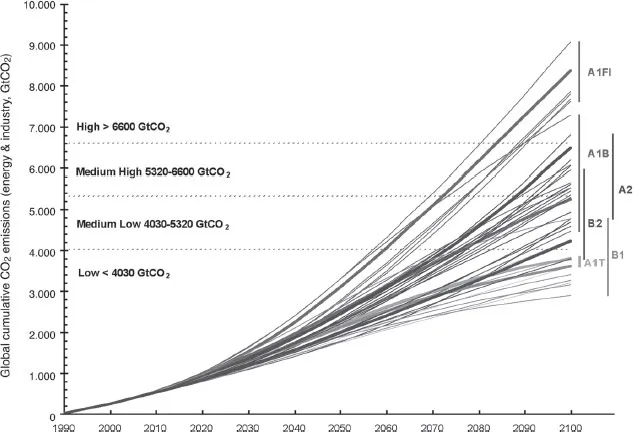

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has conducted extensive work on future CO2 emissions scenarios, the so-called ‘SRES scenarios’ (Nakicenovic et al., 2000). It has provided a wide range of future CO2 emission scenarios to 2100, from emissions only slightly greater than the level in 1990 to six times 1990 levels. The annual and cumulative global CO2 emissions from several of the SRES scenarios are shown in Figure 1.1, from which it can be seen that scenarios with very different storylines can result in similar emissions levels, whilst scenarios with similar storylines can show extensive divergence in terms of emission levels. None of the SRES scenarios included CO2 capture and storage or indeed other climate policy-driven technological developments.

Figure 1.1 Annual and cumulative global carbon dioxide emissions arising from the SRES scenarios (in GtCO2)

Source: Fig. 8.3, page 350, IPCC (2005)

By 2030 most of the IPCC SRES scenarios show an increase in CO2 emissions of between 1.5 and 3 times the level in 1990. The IPCC emission scenarios translate into an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration from 540 ppmv (parts per million of unit volume) to 970 ppmv by the year 2100 compared to the current level of 370ppmv (Watson et al., 2001). Until recently an atmospheric CO2 concentration of 550 ppmv was regarded by many climate scientists as an appropriate global target for meeting the objective of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as set out in Article 2, namely: ‘stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’. More recent scientific research suggests that 550 ppmv may well be too high a value and that 400 to 450 ppmv is perhaps a more appropriate target (DEFRA, 2004; Meinshausen, 2006). Even under an optimistic scenario with regards to adoption of low- and zero-carbon energy technologies, therefore, limitation of the build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere from anthropogenic sources will be a significant challenge over the course of the twenty-first century.

The difficulty of controlling future CO2 emissions globally is illuminated by the case of China, where approximately one GW of coal powered generation is currently being installed every week, equivalent to the entire capacity of the UK electricity network every year (HoC, 2006). Under one typical scenario, total CO2 emissions in China are expected to double by 2030 (relative to 2002) to approximately 7 GT CO2 per year, compared to an anticipated 4.5 Gt CO2 per year in the European Union (EU) (which compares with the current EU value of 3.7 GT CO2 per year) (Senior, 2005). The increased carbon emissions arising in China result largely from a doubling in the use of coal by 2030 (relative to 2002). By 2030, China is expected in this scenario to have nine times the installed coal power plant capacity as the EU and to be using five times as much coal (Senior, 2005). According to a different study, the additional CO2 emissions from coal-fired power in China and India by 2030 will be 3 gt CO2, equivalent to 13 times the UK’s current Power-Sector CO2 emissions (HoC, 2006).

UK anthropogenic CO2 emissions are in the order of 0.56 Gt CO2 per year, less than 2.5 per cent of global emissions. Setting out to demonstrate international leadership on action against climate change, however, the UK Government set a national target of 60 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050 in its Energy White Paper (2003). The 60 per cent reduction was derived through a Contraction and Convergence approach1 (Meyer, 2000) to meet the 550 ppmv atmospheric CO2 concentration stabilisation target (RCEP, 2000). To meet the 450 ppmv CO2 target would require a reduction in UK CO2 emissions of between 80 and 90 per cent (relative to 1990) (Anderson et al., 2005).

The most widely known approaches and technologies for CO2 emissions reduction are reducing energy demand (e.g. through energy efficiency or behavioural changes), renewable energy technologies and nuclear power. At whatever level of energy use, the ultimate goal must be to establish a sustainable, largely carbon-free, energy supply that is sufficient to satisfy the energy demands of the World’s industries, agriculture, transport and domestic usage. Constraining growth in per capita energy consumption would greatly assist in meeting this goal, though it is perhaps only a true optimist who would put faith at the present time in our ability to substantially reduce energy demand in post-industrial economies and restrain its growth in industrialising nations. Currently, carbon-free energy technologies are far from being developed and/or deployed sufficiently to meet global demands, nor is there a reasonable prospect that they can match current or future demands in the foreseeable future (Deffeyes, 2005). To re-iterate the point made above, the continued use of fossil fuels and associated emissions of CO2 probably remain an inevitable part of the foreseeable future. Thus it has become urgent that supply side approaches to reducing these emissions from fossil fuel use are developed along side measures to reduce demand and programmes to further develop and deploy nonfossil fuel-based energy technologies.

During the 1990s, a new technology has emerged which offers an additional route to large-scale CO2 emissions reduction. This is through the capture of CO2 from large point-sources such as power stations, oil refineries and chemical and metal works and the storage of that CO2 in suitable geological reservoirs, a technique known as carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) (Holloway, 1997; DTI, 2003). Decarbonised energy carriers, such as electricity and hydrogen, can thereby be made from fossil fuels with 80–90 per cent of the CO2 captured. Such energy carriers could eventually be used for transportation as well as for a myriad of other energy supply applications. If CO2 is captured from the combustion of biomass, a net reduction of CO2 from the atmosphere is possible, as biomass crops take up atmospheric CO2 (known as biological sequestration). This net reduction would allow the continued use of carbon-based liquid fuels in premium applications such as aviation whilst avoiding increased concentration of atmospheric CO2 (Read and Lermit, 2005; Rhodes and Keith, 2005).

Geological CO2 storage is now becoming established as a mainstream contender in the portfolio of climate change mitigation measures available. Internationally, it has been the topic of a Special Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2005) which presents a comprehensive description of the key technologies associated with capture, transport and storage of CO2 and the implications of the inclusion of CCS within the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). We have made every attempt not to duplicate the content of the IPCC report here by focusing on the UK context in more detail. In section 1.3, however, we do summarise some of the key findings of the IPCC report at the global scale in order to provide a context for the research we report on in this book.

The British Government has made various statements in support of pursuing CCS further, following on from reports published between 2003 and 2005. In March 2005 the Chancellor, Gordon Brown, announced that he would be looking into providing further incentives for CCS during 2005, followed by the announcement of the Carbon Abatement Technologies Strategy from the DTI which committed £25 million to CCS projects (DTI, 2005). The Chancellor added a further £10 million for CCS technology demonstrations in December 2005 (HoC, 2006). In February 2006 the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee produced an important report on CCS, which strongly supported deployment of CCS in the UK context and the need for government incentives to be put in place (HoC, 2006). Meanwhile, the UK Government published a new Energy Review in 2006 which favoured a new nuclear build programme and anticipated a relatively modest role for additional incentives for encouraging CCS technology.

The research documented in this book is, in essence, an attempt to translate the principles and technologies set out in the IPCC report into practice in the specific context of a national energy system, taking account of the particularities of electricity generating plant and infrastructure, legal and regulatory frameworks, environmental impacts and assessment, stakeholder and public perceptions and priorities and government policy.

1.2 Biological Sequestration, Direct Ocean and On-Shore CO2 Storage

In this book we have not explicitly examined biological sequestration. The uptake of CO2 by trees and soil and their potential role in CO2 reduction has been extensively investigated elsewhere (e.g. IPCC, 2000). It is sufficient to comment here that biological sequestration faces considerable challenges of reversibility, monitoring and verification, wider social impacts and long-term security of the carbon store (ibid. and Brown et al., 2004). CCS has considerable advantages over biological storage on these aspects, provided that rigorous standards are in place and maintained.

Many potential geological storage reservoirs in the UK are located offshore, below the sea bed, and this has sometimes led to geological CCS becoming confused with direct ocean storage. In this latter approach, CO2 is transferred directly into the deep oceans rather than being stored in geological rock formations. Ultimately (on millennial time-scales) ~80–85 per cent of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emitted to the atmosphere will be taken up by the oceans. Takahashi (2004) estimates that nearly half the anthropogenic carbon emitted since 1800 has entered the oceans already. The deep ocean has an enormous potential capacity of ~38,000Gt and the basis for the concept of direct ocean storage is to short-cut the natural processes whereby carbon dioxide is transferred into the deep ocean. Ocean pH has already declined by 0.1 pH units and Caldeira and Wickett (2003) have estimated that if all fossil fuels were to be burnt ocean pH would eventually drop by ~0.7 units. There is evidence that carbon dioxide emissions are already radically altering the oceans’ calcium carbonate system and hence are beginning to have a serious impact on the biota (Feely et al., 2004; Sabine et al., 2004). The oceans turn over on millennial time-scales so if the deep ocean carbon dioxide content is increased more there is the possibility that the deep upwelling water will eventually vent more carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere.

Direct ocean storage is a highly controversial approach because of the large degree of uncertainty in our knowledge of the fate of CO2 so stored over hundreds and thousands of years. It has not been demonstrated at a pilot or demonstration scale and has not been included for further consideration in this volume. The decision to exclude ocean storage was clear in the UK context because of the ready availability of suitable geological storage sites within the continental shelf making any higher-risk strategy of direct ocean storage unnecessary. The project team also took the decision to concentrate on off-shore storage in geological formations, and not to conside...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Underground Storage of Carbon Dioxide

- 3 Engineering Feasibility of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage

- 4 Geological Carbon Dioxide Storage and the Law

- 5 The Public Perception of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage in the UK

- 6 A Regional Integrated Assessment of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage: North West of England Case Study

- 7 A Regional Integrated Assessment of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage: East Midlands, Yorkshire and Humberside Case Study

- 8 The Implementation of Carbon Capture and Storage in the UK and Comparison with Nuclear Power

- 9 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Index