eBook - ePub

Eastern European Railways in Transition

Nineteenth to Twenty-first Centuries

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the nineteenth century, railway lines spread rapidly across Europe, linking the continent in ways unimaginable to previous generations. By the beginning of the twentieth century the great cities of the continent were linked by a complex and extensive rail network. Yet this high-point of interconnectivity, was abruptly cut-off after 1945, as the Cold War built barriers - both physical and ideological - between east and west. In this volume, leading transport history scholars take a fresh look at this situation, and the ramifications it had for Europe. As well as addressing the parallel development of railways either side of the Iron Curtain, the book looks at how transport links have been reconnected and reconfigured in the twenty years since the reunification of Europe. In particular, it focuses upon the former communist countries and how they have responded to the challenges and opportunities railways offer both nationally and internationally. Including contributions from historians, researchers, policy makers, representatives of railway companies and railway museum staff, the essays in this collection touch upon a rich range of subjects. Divided into four sections: 'The Historical Overview', 'Under Russian Protection', After the Fall of the Iron Curtain, and 'The Heritage of Railways in Eastern Europe' the volume offers a broadly chronological introduction to the issue, that provides both a snap-shot of current debates and a starting point for further research. It concludes that in an era of increased globalisation and interconnectivity - and despite the rise of air and road transport and virtual methods of communication - railways still have a crucial role to play in the development of a prosperous and connected Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eastern European Railways in Transition by Henry Jacolin, Ralf Roth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

General Suggestions and Historical Overviews of Railways in Eastern European Countries

Chapter 1

The Baltic States – Railways under Many Masters

Augustus J. Veenendaal, Jr.

Introduction

Today they are independent nations and members of the European Union, but the three Baltic countries, Estonia (Estland, Eesti), Latvia (Lettland, Latvija) and Lithuania (Litauen, Lietuva), suffered much political turmoil and went through many changes in borders and overlords in previous centuries. In the Middle Ages, the Teutonic Knights pushed in from the West and, beginning in the sixteenth century, the Swedish kings established themselves as overlords of Estonia, and of Livland and the Duchy of Kurland, in what is now Latvia. At the 1721 Peace of Nystadt, Sweden lost most of its Baltic possessions, and Czarist Russia became the new master, while Litauen was, at least officially, part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. With the partitions of Poland in the later eighteenth century, Polish Litauen became Russian as well, with the exception of Klaipeda, then known as Memel, which was part of East Prussia.1 The Vienna Congress of 1815 mostly confirmed the existing borders. Estland, Livland, Kurland and Kowno (the northern part of Litauen) remained Russian; the southern part of Litauen was officially Polish, but under Russian domination, as Poland did not exist as a separate nation before 1918. Memel was still part of Prussia, and then, after 1871, part of the German Empire. Reval and Riga, with their generally ice-free harbours, were important commercial ports for the export of Russian grain, and Libau, while also being an important mercantile port, became the home base for a large part of the Russian Imperial Navy.

Generally, the Baltic provinces of Russia were more developed than the vast plains to the east and south, with a number of ancient but still thriving cities, and somewhat more industrialised than the still predominantly agricultural rest of Russia. Shipping and trade with Western Europe from the Baltic ports went back to the sixteenth century, and Western influence was always much more important there than it was in landlocked Russia. Even Peter the Great did not change this, although his new capital of St Petersburg did attract a number of foreigners who introduced modern methods in trade and industry. The modern textile industry, in the form of a huge cotton mill, was brought by Englishmen to Kränholm near Narva in 1857, employing British capital and know how. This factory town was nicknamed ‘a piece of England on Russian soil’.2 Industrialisation on a large scale came to Russia only late, certainly not before 1875, and, according to modern scholars, only in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Heavy industry, based on the coal and iron deposits of the Donetz area, began to be developed late in the nineteenth century, necessitating railway construction on a large scale, including to the Baltic ports to export the industrial products. The many wars in which the Russian empire was involved also played an important role in the construction of railways.3

Table 1.1 Names of places mentioned in the text in German and national languages

| Dorpat | Tartu (Estonia) |

| Dünaburg | Daugavpils (Latvia, Dwinsk in Russian) |

| Eydtkuhnen | Chernyshevskoye (Russia) |

| Königsberg | Kaliningrad (Russia) |

| Kovno | Kaunas (Lithuania) |

| Kreuzburg | Krustpils (Latvia) |

| Libau | Liepaja (Latvia) |

| Memel | Klaipeda (Lithuania) |

| Mitau | Jelgava (Latvia) |

| Narwa | Narva (Estonia) |

| Pernau | Pärnu (Estonia) |

| Pillau | Baltisk (Russia) |

| Reval | Tallinn (Estonia) |

| Tauroggen | Taurage (Lithuania) |

| Tilsit | Sovetsk (Russia) |

| Walk | Valga (Estonia), Valka (Latvia) |

| Wilna | Vilnius (Lithuania) |

| Windau | Ventspils (Latvia) |

| Wirballen | Virbalis (Lithuania) |

At the same time, the grain of the vast Russian plains was exported to a hungry Western Europe. However, transportation was the greatest problem everywhere in Russia, with bad or non-existent roads, and rivers that froze over every winter. Railways were sorely needed to boost the industrial and agricultural growth. The first most important outlet for Russian grain was Odessa, with – before 1853 – more than half of total exports over the Black Sea. Only 0.3 per cent went through Riga.4 At that time there were no railways to any Baltic port, and although Odessa too lacked a railway, distances there for ox-drawn carts were shorter, and the rivers were more navigable. After the railway reached the Baltic, Riga, Reval and Windau became the chief ports for the export of Russian grain. But despite the presence of railways, even as late as 1894, more than 1.5 million tons of grain reached the Baltic ports by road, not by rail.5

The growth of heavy industry and railways was helped in no small way by the influx of foreign capital, foreign managers and staff, and foreign methods, as solicited by the Russian minister Count Sergej Witte late in the nineteenth century. Many of the Russian railways were financed from Western Europe. They were considered eminently safe vehicles for investment, as most were guaranteed by the Russian government.6 Initially, domestic labour was poorly educated and generally uninterested in any development. Serfdom was only abolished in 1861, although there were men from this class who became entrepreneurs. Foreign labour was prominent, especially among foremen and the higher echelons of managers. For instance, the Russo-Baltic Company in Riga, a maker of railway rolling stock which opened in 1869, depended heavily on German entrepreneurs and foremen.7 The large Lugansk locomotive factory was founded in 1896 by Gustav Hartmann, a close friend of Witte, a son-in-law of Alfred Krupp of Essen, and connected to Richard Hartmann’s Sächsische Maschinenfabrik in Chemnitz. Similarly, the Russian Locomotive and Construction Company of Kharkov, founded in 1895, was initiated by a Frenchman, Philippe Bouhey.8

Railways in the Russian Baltic Provinces

In the still largely undeveloped economy, communications were primitive. Bad roads, impassable in winter and dusty in summer, hampered movement. A regular service of stagecoaches between St Petersburg and Moscow was first initiated in 1820. The coaches took four to five days for the whole route. A similar service between St Petersburg and Riga by way of Pskov was started only in 1841.9 Before that it could take days to travel over the few hundred miles between the two cities. River traffic was always popular, but in winter the rivers froze over and became useless. Boatmen used to winter en route and continue their journey in the next spring.

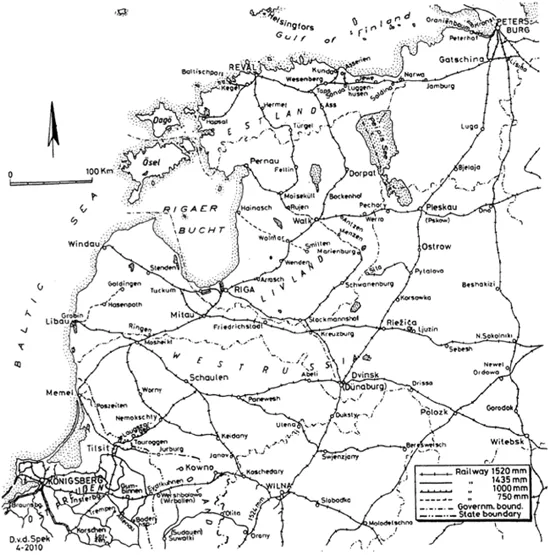

Figure 1.1 Railways in the Russian Baltic provinces, 1914

Source: Map drawn by Dick van der Spek, Emmen, the Netherlands.

The first railway in Russia was the short line from St Petersburg to Tsarskoye Selo, a summer palace of Czar Nicholas I. The line, some 14 miles long, was designed by Franz Anton von Gerstner, a leading Austrian engineer, and opened late in 1837. Steam locomotives came from England and Belgium initially; only in 1856 was the first Russian one built. The gauge chosen by von Gerstner was six feet, not for strategic reasons but for technical ones.10 In 1899 the line was taken over by the recently formed Moscow, Windau & Rybinsk Railway, and in 1903 the gauge changed to the then-standard Russian gauge of five feet.

The second railway in Russia was the Nicholas Railway between Petersburg and Moscow. Its first section opened in 1847. Engineered by the American George Washington Whistler and his sons, this line was to set the example for the Russian network that was to come.11 Whistler chose a gauge of five feet, because it would be cheaper than the six feet of the Tsarskoye Selo line. There is no proof that military strategic reasons were involved in the choice of the five-foot gauge. Whistler argued that the six-foot gauge would be too expensive for the whole network, but did value the greater stability and capacity of the wide gauge. As he needed to placate the proponents of the six-foot gauge, he came up with five-foot gauge as a compromise. Apparently he did not foresee that the Russian network might one day be connected with Western Europe.12 Most of the capital needed for the construction – 121 million rubles in all – of the Nicholas Railway was provided by Dutch and German investors. No less than 70 million rubles came from Amsterdam and Berlin in the form of five loans at 4.5 per cent interest.13 The Netherlands would remain a large investor in Russian railways, although some contemporaries compared this to David financing Goliath. British and French interests later took over the leading role, but the Dutch capital market remained an important source for Russian railways and governments.

The first line to a Baltic port was from Dünaburg to Riga (135 miles), opened in 1861. The Riga Board of Trade was behind this successful scheme. Dünaburg (in Latvia; known as Dwinsk starting in 1893 and Daugavpils since 1917) was already on the St Petersburg–Pskov–Wilna line that went on to Warsaw, so connections with Western Europe were ensured. The main reason behind this scheme, though, was the link with the Russian heartland. The government guaranteed that loans would be repaid at 4.5 per cent interest, making this an excellent investment for foreign capitalists.14 An English consortium obtained the concession for a Dünaburg–Vitebsk line, again on very favourable conditions for the shareholders, including a five per cent interest guarantee.15 A competitor for the grain export was the Moscow, Windau & Rybinsk Railway. This opened in stages between 1899 and 1904, and gave Windau and Riga a fairly straight, 1,523-mile-long connection with the Russian agricultural regions.16 In 1899 a guaranteed loan was floated for this company, with bonds of £500 at 4 per cent; the text of the bond was in Russian, English and German, a clear sign of the interest of foreign capitalists.

An earlier line from Riga to Mitau, begun by Russian entrepreneurs in 1859 without any government guarantee, was finished only in 1868. More important was the Baltic Railway Company’s St Petersburg–Tallinn line, which opened in 1870.17 In 1893, that line was combined with the Pskov–Riga Railway of 1889 to form a new Baltic & Pskov–Riga Railway, which, in 1906, became part of the state-controlled North-Western Railway.18 Another line important for the grain export was the Libau-Romny Railway. The first section from Libau was opened in 1871, followed two years later by the section through Wilna to Romny, making it an ideal outlet to West...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Abbreviations

- Notes on Contributors

- General Editor’s Preface

- Preface

- Introduction: Eastern European Railways in Transition

- PART I: GENERAL SUGGESTIONS AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEWS OF RAILWAYS IN EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES

- PART II: UNDER RUSSIAN PROTECTION

- PART III: AFTER THE FALL OF THE IRON CURTAIN: CHANGES – PROBLEMS – MODERNISATION

- Index