eBook - ePub

Collage in Twentieth-Century Art, Literature, and Culture

Joseph Cornell, William Burroughs, Frank O’Hara, and Bob Dylan

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collage in Twentieth-Century Art, Literature, and Culture

Joseph Cornell, William Burroughs, Frank O’Hara, and Bob Dylan

About this book

Emphasizing the diversity of twentieth-century collage practices, Rona Cran's book explores the role that it played in the work of Joseph Cornell, William Burroughs, Frank O'Hara, and Bob Dylan. For all four, collage was an important creative catalyst, employed cathartically, aggressively, and experimentally. Collage's catalytic effect, Cran argues, enabled each to overcome a potentially destabilizing crisis in representation. Cornell, convinced that he was an artist and yet hampered by his inability to draw or paint, used collage to gain access to the art world and to show what he was capable of given the right medium. Burroughs' formal problems with linear composition were turned to his advantage by collage, which enabled him to move beyond narrative and chronological requirement. O'Hara used collage to navigate an effective path between plastic art and literature, and to choose the facets of each which best suited his compositional style. Bob Dylan's self-conscious application of collage techniques elevated his brand of rock-and-roll to a level of heightened aestheticism. Throughout her book, Cran shows that to delineate collage stringently as one thing or another is to severely limit our understanding of the work of the artists and writers who came to use it in non-traditional ways.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collage in Twentieth-Century Art, Literature, and Culture by Rona Cran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & History of Modern Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Habitat New York: Joseph Cornell’s ‘imaginative universe’1

‘Wonderful, irrational discovery’: Cornell, Collage, and the World of Art

Beneath Joseph Cornell’s rather staid little Dutch house in Flushing, New York, lay his factory, filled with parts waiting to be assembled – with worlds, unconstructed. Plastic shells, watch parts, springs, white pipes, owl cut-outs, glass cubes, magazine articles, sheet music, ticket stubs, old books, photographs, and coins were amongst the countless articles that lingered, portioned off according to type but nevertheless haphazardly, in the pregnant dark of his basement. In some senses it was a dream factory, not so very far removed from Roald Dahl’s BFG’s cave, its shelves lined with the captive dreams that he would spend a lifetime bestowing in the form of strange gifts upon children and the childlike. His mother’s kitchen, which she shared, rather begrudgingly, with her artist son, doubled as a sort of operating theatre in reverse, on whose dissecting table these sovereign parts – objects, images, films – were not so much cut apart as lovingly cut together, by a nocturnal architect-cum-switchboard-operator speaking ‘his open sesame … to a vast and total other dimension’.2

This chapter will suggest that the city of New York, in which Cornell lived for his entire life, was the fundamental component of his life’s work, and assert that it was the practice of collage that enabled him to carry it out. Broadly, it will consider his relationship with the city in which he lived, examining his dialogue with the European avant-garde within that context, and assessing the problems that occur when his work is too closely associated with the Surrealist movement in particular. Beginning by exploring why Cornell used collage, and considering his discovery of it in the light of the artistic apprenticeship he received from the streets of New York, I will argue for an anthropological as well as a literary and art historical approach to his work. The special reciprocal link that collage provides between habitat, artist, and work of art will be demonstrated by an examination of Cornell’s childhood, his aesthetic tastes and his love of the city. Following on from this, the significance of his discovery of Max Ernst’s collage novel, La femme 100 têtes, at the Julien Levy Gallery in Manhattan, will be posited, as I introduce the problem of comparing Cornell’s work too closely with Surrealism. Looking in detail at Cornell’s first collages, I will assess his faux-nostalgia for a Europe that existed primarily in his imagination, considering whether his recreation of fleeing images and intersecting glimpses are in fact more Symbolist than Surrealist. Establishing Cornell’s eclectic, selective approach to European art and conducting a sustained comparison of his collages with some by Ernst, I will explore Cornell’s ability to raise the Surrealist formula above its own standards, enabled by his unique vision of the world. The comparison with Ernst will subsequently lead into an exploration of representations of childhood in Cornell’s work. Finally, I will discuss the sense of privacy and shared confidence in Cornell’s body of work, compared with the politics and violence of the European avant-garde, taking into consideration his use of dolls and images of women, his physical manifestations of thought, his creation of fragmentary visual narratives, and his lifelong compulsion for sharing, bartering, and passing things on. Whilst my chief focus will be on Cornell’s two-dimensional paper collages, it is important to note, as I mentioned in my introduction, that his boxed constructions are also best viewed as three-dimensional collages, which emerged naturally as an extension of his early work in paper. Collage was Cornell’s first love and key artistic tool; it enabled him to energetically reframe the frustrations of his working and domestic life in a positive light, and to narrate the story of his life in New York City in unique and uncompromising terms.

Cornell began to make art in 1931, something of an artistic greenhorn at the age of twenty-seven, having spent a decade working in the cloth-cutting industry, peddling fabric samples on the ‘the “nightmare alley” of lower Broadway’.3 He was in some ways like a latter-day version of the woodcutter Ali Baba, transported from the forests of Persia to the concrete jungles of New York City, where he was forced to earn a frustrated, alienated living out of a valuable commodity in order to support his fatherless family. It was here, in Manhattan, that he first made his ‘wonderful, irrational discovery’4 of collage, the open sesame exported from Europe in the minds and travelling cases of a throng of artists and writers, which was for him the password to that cave of treasures, the art world, revealing it to him, and granting him access, without ever requiring that he learn how to draw or paint.

Despite his lack of formal training, Cornell was able to accommodate himself very successfully within the context of twentieth-century art by making use of this exported practice; in fact, it was typical of him to use it, it being in a sense the very first scavenged, recycled, or found idea in the long line of many that would make up his career. By the time Cornell happened upon collage, in the backroom of an art gallery on Madison Avenue in 1931, it had become a prevailing artistic mode, and was continuing to be instrumental in promoting the role of the artist not just as painter but also as storyteller, architect, and thinker, advocating the associative processes of art construction over and above traditional estimations of painterly talent and finished products. From the angled vernacular of Cubist art to the frenetic vortexes of the Futurists and the seductive, sadomasochistic dreamscapes of Surrealism, collage encouraged experimentation and the idea of unlimited possibility. It also emphasised the value of the working process, meaning that Cornell, who had not so much as picked up a paintbrush since high school, was able, with relative ease, to align himself with the European artists in whose company he soon found himself. The only artistic apprenticeship he received took place as he traversed the streets of New York City, delivering cloth samples and simultaneously crafting in his head a ‘collage of things seen’.5 The art of collecting is fundamental to the collage practice. Both mentally and literally, Cornell scrapbooked pieces of the city – ‘NY ephemera’,6 as he put it – from Victorian ornaments found in thrift shops to the girls he saw in theatre box offices, finding, as Deborah Solomon notes in her biography, ‘connections where others saw only fragments’.7 For Cornell, as for Frank O’Hara, writing over thirty years later, New York was a ‘jungle of impossible eagerness’ (CP, 326), overflowing with possibilities for collecting and constructing art.

John Ashbery, in 1989, observed that Cornell was ‘almost universally recognized by artists and critics of every persuasion – a unique event amid the turmoil and squabbles of the New York art world’.8 His remark sustains the views of Solomon, who notes that ‘artists who agreed on little else agreed on Cornell’, and Brian O’Doherty, who reflects that Cornell was ‘one of those rare artists whose universe is … so imaginatively authoritative that it corrects the narrow views we accept without question from the official “art scene” itself’.9 O’Doherty correctly attributes much of Cornell’s ability to appeal to and inspire other artists to his vast aesthetic ‘range of territory’ and ‘the fact that his art includes all the others’. His identification of the lynchpin of Cornell’s oeuvre as being ‘the most mundane grounding in present experience’ highlights the profound and wide-ranging significance of the habitat out of which he worked, both in terms of his own inspiration and, subsequently, in inspiring others. To borrow from Jed Perl, Cornell ‘gave esotericism a contemporaneity by suggesting that these were the thoughts that might come to any twentieth-century man as he ambled the streets of a democratic city and gathered curious images and bits of information’.10 Certainly Cornell was particularly influenced by Surrealism, but, over the four decades in which he made art, the ‘present experience’ through which he lived was necessarily shaped to a great degree by the art world of New York City, which naturally included the Surrealist movement, but also comprised the precedents set by the French Symbolists and American Realists, by the Transcendentalists, by the city’s rival affections for Cubism and Futurism, by the not-quite-credible Neo-Romanticists, and by the rising stars of Abstract Expressionism in the late 1940s and 1950s, and Pop Art in the 1960s. It is possible to distinguish traces of all these in Cornell’s body of work, without feeling that any ever seek to govern an artwork outright (in the distinctly Cubist collage backdrop to the 1953–1954 piece A Parrot for Juan Gris, made up of pasted newsprint, for instance, or in the notably abstract Blue Sand Box, from 1950). The links between these movements and Cornell’s work is, rather, one that he cultivated himself; one discerns discrete lines of communication with individuals he admired rather than wholesale deference to any particular school or manifesto. Cornell has often been incorrectly labelled a recluse, but in fact he never shut himself off from the world, manifesting a lifelong alertness to the currents and vicissitudes of his habitat and surroundings. The enigmatic qualities of his work, of which he himself is often the deconstructed subject, have resulted in varying critical perceptions of what he was like as a person: was he reclusive, damaged, obsessed with the past, Surrealist, childlike, prematurely aged, or sexually odd? It is interesting that his work generates this kind of response (and certainly all of these traits can be discerned in his work), but too often critics have felt the need to choose between them, or to characterise him according to their own expectations, rather than critiquing him using the collage principles that he himself fostered and disseminated, and allowing him to be represented as a combination of many character traits, influences, and experiences.

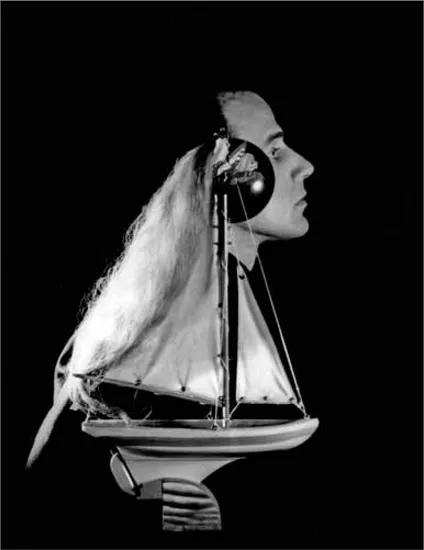

A photographic collage portrait, created between 1933 and 1934, is emblematic of Cornell’s approach to each of the art movements with which he was surrounded, and with which he has since been associated, to a greater or lesser degree. The collage photograph (Figure 1.1), taken by the young photographer Lee Miller, features Cornell’s face as the outsized figurehead of a model sailing boat, with a long skein of blonde hair floating strikingly behind it against a dark background. It is an illustration of the type of artistic synthesis for which Cornell strove, embodying vessel and androgynous voyager as a unified entity in a shadowy setting, and demonstrating, as Dickran Tashjian notes, Cornell’s ‘affinities with the androgynous imagery that existed on the margins of the Surrealist group among women artists disaffected by its male domination and often violent if not misogynous images of women’.11 The creative exchanges that Cornell had with women on the fringes of Surrealism, such as Miller, the painter Leonor Fini, and the painter, writer, and set-designer Dorothea Tanning, ‘offered lessons of autonomy: Miller, by breaking with Man Ray and forging her own career as a photographer; Fini, by refusing to join the Surrealist movement in the first place; and Tanning, perhaps most of all, by striving for her own artistic authenticity’.12 Cornell learned a great deal from these women and from others, including the ballerina Tamara Toumanova and, later, the writer Susan Sontag, all of whom reinforced his sense of the importance of unfailing artistic experimentation and the need to push or even disregard boundaries, rather than allowing oneself to fall easily within one identity category or another, either socially or creatively. This is also, of course, one of the principle lessons of collage: the continuous cross-pollination of discrete fragments results in striking singularity of product and infinite aesthetic possibilities that simultaneously allow and deny creative autonomy.

Fig. 1.1 Lee Miller. Joseph Cornell, New York Studio, 1933. Black and white photograph. © Lee Miller Archives, En...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Catalysing Encounters

- 1 Habitat New York: Joseph Cornell’s ‘imaginative universe’

- 2 ‘Confusion hath fuck his masterpiece’: Re-reading William Burroughs, from Junky to Nova Express

- 3 ‘Donc le poète est vraiment voleur du feu’: Frank O’Hara and the Poetics of Love and Theft

- 4 Bob Dylan and Collage: ‘A deliberate cultural jumble’

- Conclusion: ‘Yield us a new thought’

- Bibliography

- Index