![]()

Chapter 1

Coinage and the Economy of Syria-Palestine in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries CE

Alan Walmsley

Understanding the production (minting), distribution and circulation of coinage in Syria-Palestine during the 7th and 8th centuries has undergone far-reaching improvements in recent decades. In the last few years progress has been especially swift, over which time the implications of these advances have also been steadily – and increasingly – applied to an understanding of the early Islamic economy, and ever more successfully so.1 By this means a valuable dynamic between coin studies and historical endeavour is being forged, and few would now question that “progress does seem to have been made in breaking down the divisions between ‘coin people’ and ‘historians’”.2 Although still in a formative stage, this new collaboration is offering fresh insights into major social developments that characterized the crucial late antique – early Islamic transitional period. This paper serves to highlight some of these developments with a focus on the mid-7th to mid-8th century in Syria-Palestine/Bilād al-Shām, although placed within a wider chronological framework. The study brings together recent work on identifying mints, minting authorities, known coin types, and the geographical distribution of coins based on an ever increasing number of archaeological site finds (unprovenanced hoards are not considered). Through a cross-disciplinary analysis of this material, in which coin profiles are compared with other archaeological material, fresh perspectives are drawn on the way coinage – notably its production and spread – serves to identify major changes to social and economic conditions in Bilād al-Shām during the late antique – early Islamic transitional period.

Mints

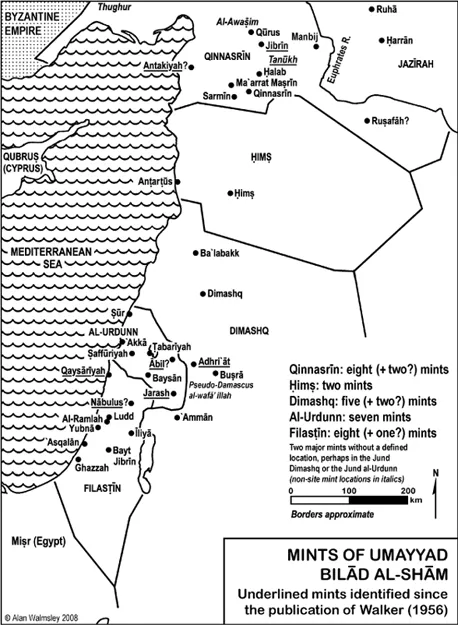

Most of the mints at which coins in gold (dīnār, pl. danānīr), silver (dirham, pl. darāhim) and especially the many copper types (fals, pl. fūlūs) were struck in early Islamic Bilād al-Shām were conveniently identified in John Walker’s pioneering and still valuable study of early Islamic coinage, mostly complied from the collection at the British Museum.3 In the last two decades, a small number of further mints have been identified and the operation of others clarified, and today a very clear map of minting activity in Bilād al-Shām can be compiled (Figure 1.1). To an extent that verges on the unduly repetitive, it has often been stated that a remarkable feature of coin production in the 7th and 8th centuries was the multiplication of towns that minted coins when compared to late Roman practices, a point emphasized by Walker. However, the connection to Classical-period traditions may be considerably more indirect than Walker suggests: “It is of interest to observe that in many instances the freshly created mints were really ancient, pre-Byzantine, mints of Classical times resuscitated, a truly remarkable phenomenon” (my emphasis).4 In a post-colonial world, such a statement should be read for what it is.

Figure 1.1 Mints of Umayyad Bilād al-Shām, by province (jund). Source: author, 2008, based on Album and Goodwin 2002, Bone 2000, Goussous 2004, Ilisch 1993, Ilisch 1996, Walker 1956

Since Walker, a few more minting centres in Bilād al-Shām have been identified (Figure 1.1, underlined names); however, most of the advances have been in allocating additional and sometimes new coin varieties to already known mints. Stephen Album and Tony Goodwin’s expansive study of the pre-reform (so-called “Arab-Byzantine”) coins at the Ashmolean Museum has brought these discoveries together, notably the recognition of Jarash as a mint for pre- and post-reform copper coins,5 and the identification and probable regional location of three uncertain and unexplained mints: the al-wafā’ lillah mint and the “pseudo-Damascus” mint in the north Jordan – southern Syria area, and the Tanūkh mint in north Syria.6 While Goodwin views the first two as located in the Jund al-Urdunn, stylistically they plead for inclusion in the Jund Dimashq, and if any location as such is necessary for each mint Buṣrā or even al-Jābīyah are very likely candidates. Lutz Ilisch, as repeated by Goodwin,7 has suggested that Tanūkh is not a place but the name of the minting authority, specifically the ecclesiastical administration of the Tanūkh tribe, a plausible and important proposition on which see further below. Andrew Oddy has, furthermore, proposed Ābil in the far northeast of the Jund al-Urdunn as a mint in the pre-reform twin seated figure type of Baysān and Jarash,8 but this could be Arbela (Irbid), where the governor of the trichōra of Jadar, Bayt Rās and Ābil apparently made his base, as revealed in the self-martyrdom of St Peter of Capitolias.9 Unfortunately, the surviving text on the few known coins is too garbled to be sure at this stage. Nayef Goussous, in the huge catalogue of his collection housed in the Jordan National Bank Numismatic Museum, also identifies rare issues from Adhri’āt (Jund Dimashq), Qaysārīya (Jund Filasṭīn) and perhaps Antākīya (Jund Qinnasrīn).10

This short presentation identifying the functioning Umayyad mints in Bilād alShām leaves little doubt about the active – almost hyperactive – state of the monetary economy in the 7th and 8th centuries.11 In all, some 30 to 33 towns/localities of the approximately 68 to 73 provincial and district capitals of early Islamic Bilād al-Shām have been positively identified as coin minting centres. That is, almost half (45%) of the administrative centres in the five ajnād functioned as a mint at one time or another, but not equally either in the quantity of coins produced or the length of time a town functioned as a mint. The main structural difference with the first three quarters of the 6th century, when money sourced from central mints of the empire underpinned urban and rural economies, was the growing and, in part, enforced self-sufficiency in local coin supply, a process instigated early in the 7th century.12 Why one town became a mint and another did not, or at least failed to become an important mint, in the 7th century did not always seem to relate to matters of urban seniority, to the extent that can be assessed in this period. Glaringly apparent from Figure 1.1 is the absence of any coastal mints for the Jund Dimashq and only rare minting at sites along the coast of Ḥimṣ and Qinnasrīn, activity in north Filastīn characterized by limited production of only post reform coins at Qayāsrīya and Nābulus but none at Sabastīya,13 and the much reduced number of mints in the Jund Ḥimṣ compared to the other ajnād, although this lack was compensated by the huge output of coin by the urban mint of Ḥimṣ. Nābulus is an inexplicable omission as the source of any pre-reform issue if it was entrusted with minting coins under Heraclius,14 a suggestion that seems untenable in this light. The Neapolis on these coins presents, rather, as a Cypriot military mint, given the large number of coins from the reigns of Phocas, Heraclius and Constans II recovered on that island.15 The economic significance of these different factors, and their social implications, are important in understanding change in the period (as will be explored later in this paper), and hence the need to spent time on them at this point.

Coin Types and Chronology

The extent of monetary economic activity in Bilād al-Shām during the 7th and 8th centuries is categorically proven by the range and ...