![]()

Chapter 1

History of the Wellesley Islands

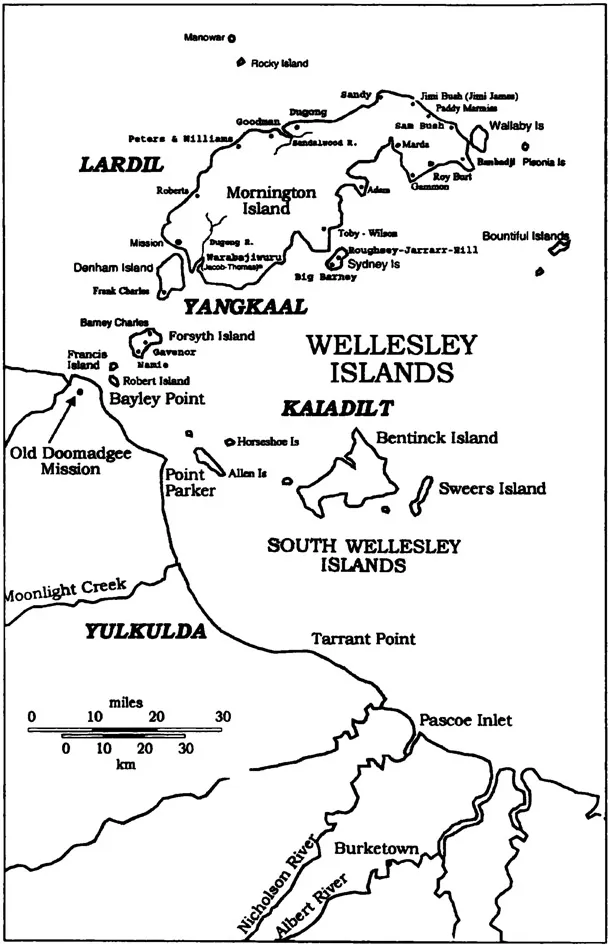

Mornington Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Queensland, is the territory of the Lardil people (see Figure 1.1). When a Presbyterian Mission was established in 1914, the Lardil population was about 230, and, as Mornington, including the small adjacent islands (Sydney Island and Wallaby Island), covered an area of 310 square miles, the population density was 0.7 to the square mile, which is a fairly high density for hunter-gatherers. For much of the year Mornington is a rewarding hunting environment as is normally the case for all the Wellesley Islands. The Lardil (and other Wellesley Islanders) were basically hunters of the sea from which they obtained (and still do so) a great variety of fish, shellfish, and also turtle and dugong. For the most part they camped along the beaches ever watchful for what the sea had to offer. Food was also obtained from the land, particularly such plant food as panja (Eleocharis dulcis), water lilies (Nymphaea spp.), pandanus nuts and wardirr nuts (Cycas), roots and berries, and various game including snake, goanna, mangrove rat, swamp turtle, duck, brolga, and wallaby.

Lardil tribal territory was divided into about 31 Countries or estates, each with a coastal and inland area (see Figure 2.1). Members of a Country were (and are) known as dulmada. By and large, people could hunt wherever they pleased without having to ask for permission, but they were only allowed to gather water lilies and panja when invited to do so by the senior member of the Country. There were a few other restrictions including obtaining consent to collect wardirr and pandanus nuts, to cut spear handles from certain species of trees, and to obtain fish from the stone fishtraps. In addition to Countries there were four Cardinal areas consisting of the northern, eastern, southern, and western people.

Of particular importance were the Windward and Leeward moieties. The Windward moiety consisted mostly of the southern and some of the eastern Countries, while the Leeward moiety consisted mostly of the northern and western Countries. There was much conflict between the moieties in the form of competitive dances, fights, and sorcery.

All young males were required to go through the first initiation (luruku) and be circumcised. They were prohibited from speaking Lardil for at least a year and during this period they communicated by sign language (Marlda kangka – hand speak). Most men voluntarily went through the second initiation (warama) and were subincised. They were then formally taught a ritual language, Demiin, which they were required to speak for one or two years. This meant that almost all their communication during this period was with fellow warama men. Women were not initiated. They had a role in the circumcision initiation but not in the subincision initiation. Although women did not speak Demiin older women had some comprehension of the language from listening to their husbands speaking it. Yangkaal Demiin was the same as Lardil Demiin.1

Figure 1.1 The Wellesley Islands

The system of land tenure, local and social organization, and the initiation ceremonies of the Yangkaal were basically the same as those of the Lardil. The two tribes intermarried, traded, held joint initiation ceremonies, and sometimes engaged in lethal fights. They both had contact with the neighbouring mainland tribes, but the Yangkaal, particularly the Yangkaal from Forsyth Island, did so more than the Lardil. The Kaiadilt of the South Wellesley Islands had little contact with the Yangkaal or the Lardil. It was dangerous for them to go far out to sea on their mangrove rafts. It was even dangerous to paddle to Allen Island, a distance of about eight miles, for a total of 17 Kaiadilt drowned in two attempts in the 1940s (Tindale 1962b: p. 309).

By and large, the Kaiadilt had little contact with outsiders until Europeans appeared on the scene. Flinders was forced to anchor at Sweers Island, in 1802, to repair his vessel and during his stay he recorded some valuable observations about the Kaiadilt (Flinders 1814: p. 137). It was only with the establishment of Burketown, in 1865, that a new world impinged on the Wellesley Islanders and the neighbouring mainland tribes. In a vain attempt to avoid a deadly fever epidemic die Burketowners fled to Sweers Island, which was an important part of the Kaiadilt tribal territory. Although there is no record about how the Kaiadilt fared, it is likely that they also suffered from the fever. They were forced to abandon Sweers for several years which must have caused them considerable hardship since it constituted some six per cent of their territory including reefs. A disgraceful callous episode was the kidnapping of Kaiadilt children for the benefit of pastoralists (May 1984: p. 69).

Burketown was re-established in 1882 and although it was only a small outpost, mainly a port for the developing cattle stations, it had a devastating influence on the local tribes. The Mingin whose tribal territory included the Burketown area have all but disappeared. Most of the Yulkulda, some of the Yangkaal, and a few Lardil visited Burketown to see the strange sights and to obtain tea, sugar, tobacco, and iron goods. Many mainland Aborigines were killed by the pastoralists and Queensland Native Police (Reynolds 1972: p. 22).

The Northern Protector of Aborigines, W.E. Roth, began to make annual tours of the Wellesley Islands at the beginning of the twentieth century. He made three journeys and contacted the Kaiadilt, Yangkaal, and Lardil. He recorded meeting a Yangkaal, in 1903, on Forsyth Island who had visited Burketown and spoke Garawa (as did other Yangkaal and Lardil) and a few words of pidgin English.2 On one trip, in 1901, an Aboriginal named Friday (who too was from Forsyth Island) accompanied him as an interpreter. Years before Friday was found on a raft and taken to Normanton. He was able to make himself partially understood by the Kaiadilt. It is obvious from Roth’s accounts that the Lardil had very little contact with White people (Roth 1903). They claimed that in the pre-Mission times they usually hid when they saw a boat passing by. There was an interesting episode, in 1890, when Rocky Island, some 12 miles to the north of Mornington, was mined for phosphate guano. The miners visited Mornington for water and firewood and one of them was speared in the thigh (Ellis 1936: p. 116). Occasionally pearlers stopped to recruit labour but the recruits were never heard of again. The last time this happened was in 1917 soon after the first missionary, Rev. Robert Hall, was murdered by a southern Lardil.

Rev. Hall visited Mornington for two days in 1912 and returned in 1914 to establish a Mission. Initially his efforts were quite successful and he had no difficulties in obtaining labour. What is remarkable is that he soon taught the Lardil and Yangkaal to man the Mission ketch and to collect and cure bêche-de-mer. He started a school but attendance was poor (Hall 1914). For the year 1916 he reported:

During the year practically all the natives on the island – viz., about 200 – have visited the Station and received some benefit. The majority, however, have come in only once or twice, and then only stayed two or three days. Consequently the average daily number has been small – 18… those belonging to the far end of the island are somewhat afraid of the tribe which frequents this end.

School has been maintained regularly, four days a week, throughout the year, though at this early stage of the mission we considered 2/4 hours a day sufficient. There have been 21 names on the roll, but, as some of these have attended very little, the average for the year is only 7. (Hall 1917)

One Mornington Islander, Peter Burketown (whose Lardil name was Kirdikal – Moon), got into trouble while working on a cattle station and he decided to return to Mornington (Trigger 1992: p. 25). He asked Rev. Hall for a job but was rebuffed reportedly because Hall thought that he was a mainlander. Hall wanted to keep the Mornington Islanders free from contact with the mainland tribes whom he regarded as a bad influence. He established strong ties with Gully Peters’ father (whom he named Peter) and he decided to explore the northern part of Mornington where Gully’s father’s Country (Biri) is located. Hall was accompanied by Gully and his friend, Paddy Marmies, who often lived with Gully’s parents. They were followed by Peter Burketown who asked Hall for tobacco which Hall refused. (He did not have any tobacco because he regarded smoking as an un-Christian habit.) Peter and his companions continued to stalk Hall and pestered him so much that he threatened them with his shotgun. Gully told me that he warned Hall that Peter was a bad man. When they arrived at Biri, Hall told Gully to camp with his family and that he would camp by himself. While he slept Peter killed him with a club and an axe. The Biri people were frightened but there was nothing that they could do because Peter threatened them with Hall’s shotgun.

Peter returned to the Mission and that night with several men he attacked the Mission. He managed to wound a missionary before he and his party were driven away. They besieged the Mission for several days but the missionaries were finally saved by the arrival of the supply launch and fled to Burketown. The police arrested Peter and his accomplices, about 12 men in all. They were sent to prison and other settlements. Peter is believed to have drowned while attempting to escape from Palm Island. Years later a few of his accomplices were allowed to return but none of them was alive when I arrived in 1966. There may have been a Windward and Leeward dimension to the killing and the attack on the Mission because most of Peter’s accomplices were, like himself, Windward. It seems that Hall favoured the Leeward people, particularly Gully’s family.

There were several consequences arising from the murder of Rev. Hall. The Lardil realized, if they had not already done so, that the Whites were more powerful than themselves and anyone who caused trouble would be taken away. Peter and his accomplices were all second-degree (warama) initiated men and their arrest was a considerable loss not only in the sense that they were members of the society but also for the ritual knowledge that they possessed. It seems that the Lardil were subdued by the consequences of Rev. Hall’s murder and they gave no appreciable trouble to his successors. There are other factors which affected the population and the people’s relationship with Europeans. In 1915 there was an epidemic of whooping cough. Hall reported the deaths of six males and three females (Hall 1916). However, from my records at least 14 adults died. They were the adults that people remembered and one can safely conclude that many children, whose names were not recalled, died from the epidemic. In addition at least two young men were taken away by pearlers and were never heard of again. There were about three homicides during the Hall years. Hence at least 27 persons (perhaps 35 all told) – including the men arrested – were lost in about three years (1915-17) which was approximately 12 per cent of the population and most likely 25 per cent of the adult population, the majority being men.3 To give some idea of the likely effects of this loss in percentage terms the loss of men was greater than what occurred among British troops in the First World War. In Goodbye To All That Robert Graves observed that when he walked through the centre of London his generation was missing.

A much debated issue has been what caused the depleted population of Australian Aborigines and how much the population was reduced since the First Fleet in 1788. Those scholars who claim that their numbers were much reduced because of the unwitting introduction by Europeans of diseases and epidemics may find support in the whooping cough deaths particularly as the sickness appeared soon after first contact, that is, after the establishment of the Mission in 1914. Other scholars who place the blame on ill treatment may also find some support in my records and even more support in what happened to the neighbouring mainland tribes in the Burketown area where the Native Mounted Police appeared on the scene, in 1868, soon after Burketown was established (McKnight 2002: pp. 27-8). A Burketown resident reported (ironically one hopes), ‘Everybody in the district is delighted with the wholesale slaughter dealt out by the native police, and thank Mr. Uhr for his energy in ridding the district of fifty-nine (59) myalls’ (Reynolds 1972: p. 22). One settler took the obscene pleasure of nailing the ears to his dwelling of Aborigines that he had killed. The differences between disease and ill treatment may be important to Europeans but for the Aborigines the end result was the same. In any event, it is not an either or matter for disease and ill treatment contributed to the drastic reduction in Aboriginal population and both were the result of the advent of Europeans.

After Rev. Hall’s death Rev. Wilson took charge in 1918 and remained on Mornington for 20 years. By the mid-1920s he erected dormitories for the children. He appointed Aboriginal policemen and councillors, and in a sense instigated indirect rule. The older people were left more or less to themselves but were encouraged to camp at three of four main sites ostensibly the better to assist them should the need arise but also to keep them under surveillance and control. Many children in the 1920s and 1930s were sent to Mornington from Burketown. Quite a few were of mixed descent with European or Chinese fathers. They belonged to several tribes: Yangkaal, Yulkulda, Yangyuwa, Garawa, and Wanyi. Gradually with the influx of these children, sometimes with their parents but more often without, and of other people, the population increased. In 1928 there were 24 persons of mixed descent – 7 males and 17 females (comprising 5 adult males and 12 adult females, 2 boys and 5 girls). By 1935 the mixed descent population had increased to 46: 15 males and 31 females (comprising 25 adults and 21 children). The total population in 1935 was 397 (see Sharp 1933-35). About this time Rev. Wilson established a community on Denham Island for a few married couples who had been raised in the Mission. This was obviously an attempt to separate them from camp life situated a few hundred yards from the Mission.

Most children who were raised in the Mission spoke English only. They made fun of new arrivals when they spoke an Aboriginal language. The children looked down on the bush people as myalls who knew nothing about the ways of White people. Older boys were allowed to leave the Mission on Saturdays and to camp with their relatives during the summer holidays, but girls could only leave when they were married. Some of the older girls purposely caused trouble by stealing and breaking into the Mission store so that they would be married and could leave. But for most young girls the threat of being expelled was enough to keep them under control (see McCarthy 1945-47). The children were taught the usual European Australian household chores and worked in the Mission garden. Rev. Wilson and his wife seem to have been well educated and judging from the results the children received more than a rudimentary education of reading, writing, and arithmetic; as one would expect religious instruction was stressed.

During Wilson’s time, there was sporadic contact with the Kaiadilt as when the Mission launch stopped at Bentinck Island on the way to and from Burketown for supplies. In an effort to increase revenue the Mission collected bêche-de-mer (trepang or sea slugs as they are commonly known) and while doing so some Mornington Islanders, particularly Gully Peters, contacted the Kaiadilt. In 1933 the bêche-de-mer industry collapsed and contact with the Kaiadilt became rarer. At the beginning of the Second World War, Rev. Wilson reluctantly departed when he was transferred to Brisbane. During the war years there were only one or two missionaries. Many children of mixed descent, mostly girls, were sent to the mainland because it was believed that they would not be able to survive life in die bush as could Aborigines of full descent. Very few returned to Mornington Some of them lived in other settlements or made their way in towns and cities. To a large extent the Mornington Islanders reverted to bush life but the Mission store was still a drawing power and some people continued to live in the village camp. During the war years a generation of young men began to work on the mainland cattle stations. They experienced a different way of life from the elders and other people who remained on Mornington. They took to cattle work with gusto and were proud of the skills that they acquired, the money they earned, and their knowledge of the Whiteman’s ways.

In 1943 Burt McCarthy (who was always referred to and addressed as Mr McCarthy) was appointed as Superintendent. He evidently saw his job as reasserting Mission authority for he considered that discipline had deteriorated during the few years of his predecessor. In 1966 he was remembered with intense loathing by the older Mornington Islanders because of his authoritarian manner. But to his credit he successfully opposed a scheme by the Department of Native Affairs and the Presbyterian Board of Missions to relocate the Mornington Islanders to a settlement in Cape York Peninsula. And in 1947-48 when the Kaiadilt were starving because of exceptionally poor hunting conditions and intra-tribal violence he arranged for them to be brought to Mornington and given medical treatment.

In 1952 Rev. Belcher replaced McCarthy and was the Mission Superintendent when I arrived in June 1966. Soon after his appointment he closed the dormitories because he believed that children should be raised by their parents. He encouraged the people to take command of their own affairs. At the same time he ...