It is, after all, very rarely possible for new ideas to find adequate expression in old forms.

–Angela Carter, ‘The Language of Sisterhood’

If we keep on speaking the same language together, we’re going to reproduce the same history. Begin the same old stories all over again.

–Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One

We must return to the innermost alchemy of the word, we must even give up the word too, to keep for poetry its last and holiest refuge. We must give up writing secondhand: that is, accepting words (to say nothing of sentences) that are not newly invented for our own use.

–Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary

In 1972, Angela Carter (1940–92) began translating a text that was to assume a pivotal role in her developing feminist poetics. This work was Xavière Gauthier's polemic Surréalisme et sexualité, which had been published in France in October 1971, and which was to define the direction of much subsequent feminist scholarship on surrealism. As is evident from her correspondence with the intended publisher of the translation, Marion Boyars, Carter was highly invested in this endeavour. In her first letter to Boyars, received on 9 October 1972, Carter writes:

I think its [sic] a very good book indeed, very erudite and extremely pertinent – its [sic] about politics and feminism as much as, if not more than, about the surrealists, though they are the jumping off point in her discussion, of course. Its [sic] polemical, very much more than a piece of art history.

She goes on to declare emphatically: ‘I’d like to translate it very, very much indeed – because I’m a woman and, in a slap-dash kind of way, an anarcho-Marxist as well as heavily into (as we in King's Cross say) the surrealist movement’ (pers. comm.; emphasis in the original).

Calder and Boyars, who contracted Carter to translate Surréalisme et sexualité, was a small independent publishing house specialising in avant-garde authors such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, Georges Bataille, William Burroughs and Hubert Selby.1 While correspondence between Carter and the publisher confirms that she submitted the complete typescript of ‘Surrealism and Sexuality’ in August 1973, the translation was never published and the project fell into obscurity. The decision not to publish the translation seems to have been Carter's alone. The correspondence between Carter, Calder and Boyars, and Basic Books, the planned publisher of the American edition of the translation, reveals Carter's anxiety that her translation would receive negative reviews. The translated text was given a damning evaluation from an editor at Basic Books who complained that ‘[w]hat may be, in French, subtle and allusive discourse becomes, in English, a hopeless garble of jargon and isms’. The editor recommended that the main body of the text be ‘laundered’, and some parts ‘entirely rewritten’ (pers. comm. [Unsigned and undated letter to Erwin Glickes]). Nevertheless, Marion Boyars informed Carter, in a letter dated 15 July 1974, that Calder and Boyars had chosen to ‘forget about the American publisher and send the book to the printers in its present version’ (Boyars, pers. comm.). The news about the negative reader's report reached Carter only a week before the translation was due to go to press. Tim O’Grady, an editor at Calder and Boyars, described how a ‘slightly freaked-out Angela Carter’ had phoned him to say that

she didn’t want the book to come out if it would be doomed to be ripped to pieces. She said she realized she took the project on leading everyone, including herself, to believe that she could handle all the technical language, but when she got into it she found that some portions of it were over her head.

(pers. comm.)

Carter withdrew the typescript for reassessment and apparently never returned it to Calder and Boyars. The translation was not published and has, until recently, remained unknown to critics of Carter's work.2 Indeed, the whole affair seems veiled in obscurity, with no adequate explanation for the aborted release being offered even to the book's author, Xavière Gauthier. As Gauthier recalls:

Je n’avais pas compris ce qui s’était passé, dans les années 73–74, avec la traduction en langue anglaise; j’avais reçu une avance pour Basic Books, puis plus rien, pas de parution, et impossible d’obtenir une explication de la part Gallimard.

I never understood what happened in 73–74, with the English translation; I received an advance for Basic Books, and then nothing else, no publication, and it was impossible to obtain an explanation from Gallimard [the French publisher of Surréalisme et sexualité].

(pers. comm., email 2010)

The typescript of ‘Surrealism and Sexuality’ was kept among Carter's private papers until 2006, when these were acquired by the British Library. Her papers were subsequently catalogued and made available to the public at the end of 2009.3 It is unclear if the 195-page typescript of Carter's translation at the British Library is the version she indeed submitted to Calder and Boyars, or whether it is an earlier draft. It contains several typos and some omissions, and, in places, even mistranslations.4 Nevertheless, in my analysis I throughout refer to Carter's typescript of ‘Surrealism and Sexuality’, rather than quoting from the original, in order to convey how Carter wrote herself into Gauthier's text.5

Taking Carter's engagement with Surréalisme et sexualité as its starting point, this study will trace the full extent to which Carter's writing from the very beginning of her career was influenced by the aesthetic and political concerns of surrealism. Hitherto, scholars have considered surrealism a marginal influence on Carter's writing, the impact of which was confined to her preoccupation with the fantastic and the bizarre in her mid- to late career. By contrast, this study will show that major strands of surrealist thought structure her writing of the 1960s and 1970s. The presence of surrealism can be traced in her work, albeit in an attenuated form, right up to her death in 1992. Drawing on Carter's fiction and non-fiction, as well as her newly available private journals and manuscripts, I will illuminate the ways in which Carter appropriated, experimented with and developed surrealist aesthetics and politics throughout her work. Moreover, whereas Carter herself often mentioned the surrealists as a source of inspiration for her writing, she de-emphasised the crucial significance scholarship on surrealism played in her understanding of the movement – a significance that has also eluded earlier scholars of her work. The present study aims to show that Carter's literary project developed not only in relation to her own, in many ways haphazardly constructed genealogy of surrealism, but also in relation to her research into scholarship on the movement.6

Carter's translation of Surréalisme et sexualité, I argue, coincides with a significant shift in her relationship to surrealism in the early 1970s, when her increasing interest in feminism and the politics of desire lead her to interrogate surrealist visual and literary representations of women in a more sustained manner. This intensified critique of surrealist representations of women begins with the publication of The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972), and was consolidated and further developed by her encounter with Gauthier's polemic. Carter's early fiction of the 1960s had been influenced by surrealist poetry (in particular that of André Breton) and by the iconoclastic cinema of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, and was characterised by experimentation with estrangement and dream logic. Even though these earlier works employ surrealist techniques largely in order to display patriarchal oppression, my analysis shows that they do so without critiquing the masculine bias of surrealism itself. By contrast, Carter's writings of the 1970s, particularly after her translation of Surréalisme et sexualité, confront surrealist art and literature with a clearly stated feminist critique. This critique is advanced by an exuberant and parodic literary mode usually associated with surrealism itself, showing Carter's indebtedness to the movement even as she challenges it.

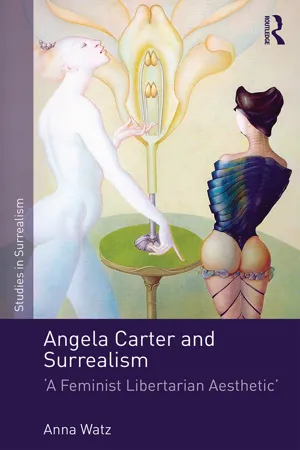

This study will show that Surréalisme et sexualité not only had a major impact on Carter's re-evaluation of surrealism, but also shaped the development of her entire feminist project. Gauthier's polemic, as I will show, is a key intertext in Carter's writing of the second half of the 1970s and strongly influenced her most distinguishing feminist strategy – her method of ‘demythologising’, which characterises Carter's writing from the mid-1970s onwards, most notably in The Sadeian Woman: An Exercise in Cultural History (1979) and The Passion of New Eve (1977), the latter of which she calls her ‘one anti-myth novel’ ([1983] 1998, 38). Moreover, for Carter, Surréalisme et sexualité provided a powerful illustration of what, in a letter to Boyars, she called a ‘feminist libertarian aesthetic’ (pers. comm. [Letter to Marion Boyars, dated 31 August 1973]). This aesthetic, I argue, for a period in the mid- to late 1970s provided a model for her own writings. Carter, like Gauthier, ambivalently embraces the surrealist goal of liberating the erotic imagination through finding a new language with which to represent gender and sexuality. Simultaneously, both writers charge the surrealists with having failed to imagine desire outside a patriarchal logic. In Carter's fiction, however, there is an increasing sense that it might not be possible to speak from such a space, outside the power structures of language and culture.

Carter's feminist-surrealist aesthetic can arguably be seen as contributing to a revisionist history of the avant-garde, one that considers certain strands of 1970s experimental feminist writing as a continuation and an elaboration of what we have come to think of as the historical avant-garde. This revisionist project characterises Susan Rubin Suleiman's influential Subversive Intent: Gender, Politics, and the Avant-Garde (1990), in which she promotes the thesis that ‘a genuine theory of the avant-garde must include a poetics of gender’, which is ‘indissociable from a feminist poetics’ (1990, 84). Her definition of the avant-garde, then, strategically encompasses feminist postmodern writers and theorists as well as what we have come to consider ‘the historical avant-garde’. More recently, Griselda Pollock has made a similar call for a reconsideration of received notions of the avant-garde project, in order to counter the ‘linear temporality associated with the avant-garde’ that has produced a ‘monogendered, selective narrative of modern art’ (2010, 796, 795). Instead Pollock suggests that:

there were diverse and discontinuous avant-garde moments at which the defining collision of social and aesthetic radicalisms occurred. While women generally participated in canonical avant-garde moments, there were also some more specific moments particularly attentive to gender and sexual difference. One of these arose in the encounter between feminism and art circa 1970.

(796; emphasis in the original)

If we consider Carter's feminist literary project as part of such a reconfiguration of the avant-garde in general, and surrealism in particular, we must open its definition to comprise works that, like Carter's, contain elements of both theory and aesthetic practice. We might include French feminist writers such as Hélène Cixous and even Gauthier herself in this hybrid category of scholarship and creative avant-garde writing.

Feminisms in Flux

Walter Benjamin once referred to surrealism as ‘The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’ ([1929] 1979, 225). Perhaps with a nod to both Benjamin and surrealism, Carter wrote in 1988 that ‘[t]he sixties were the first, and may well turn out to be the only, time when we had an authentic intelligentsia in this country just like the ones in Europe and America’ (1988, 209–10). The echo of Benjamin is not incidental, but underscores an important link between surrealism, Marxism and the 1960s new avant-gardes. In France, new radical movements such as Tel Quel and the Situationist International had developed in close proximity to surrealism and Marxism (see Plant 1992, 1). The end of the decade saw a quickly growing revolutionary movement, culminating in the student protests in Paris in May 1968. One of the most important theorists of this ‘counterculture’, Herbert Marcuse, was a firm advocate of surrealist ideas. His own libertarian philosophy had its origins, like surrealism itself, in a blend of the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Whereas surrealism itself ‘never travelled across the Channel, not even in the 1930s’ (Carter [1978] 1998, 512), the revolutionary spirit that had fuelled the student upheavals in Paris took hold in the UK, and paved the way for what Carter identifies as ‘a brief period of public philosophical awareness that occurs only very occasionally in human history; when, truly, it felt like Year One, that all that was holy was in the process of being profaned and we were attempting to grapple with the real relations between human beings’ ([1983] 1998, 37).7 What Benjamin had described as surrealism's potential to bring about ‘profane illumination’ – a ‘loosening of the self by intoxication’ powerful enough to spark both personal and social revolution – seems also to characterise Carter's experience of the 1960s (Benjamin [1929] 1979, 227). More than this, Carter acknowledges, towards the end of the decade,

there was a yeastiness in the air that was due to a great deal of unrestrained and irreverent frivolity. … Sexual pleasure was suddenly divorced from not only reproduction but also status, security, all the foul traps men lay for women in order to trap them into permanent relationships. Sex as a medium of pleasure. Perhaps pleasure is the wrong word. More like sex as an expression of is-ness.

(1988, 212, 214)

However, while the 1960s discourses of liberation succeeded in challenging issues of both class and sexual repression, it became increasingly apparent towards the end of the decade that the issue of sexism had been left largely unaddressed. As Toril Moi notes, in many politically progressive movements in both America and Europe, ‘women were experiencing [a] discrepancy between male activists’ egalitarian commitment and their crudely sexist behaviour toward female comrades’ ([1985] 1995, 22) They had ‘fought alongside men on the barricades only to find that they were still expected to furnish their male comrades with sexual, secretarial and culinary services as well’ (95). Carter attests to the same experience, confessing that ‘all the time I thought things were going so wel...