- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Travel, Space, Architecture

About this book

Travel, Space, Architecture defines a new theoretical territory in architectural and urban scholarship that frames the processes of spatial production through the notion of travel. By aligning architectural thinking with current critical theory debates, this book explores whether dissociating culture from place and identity, and detaching the idea of architecture from both, can reframe our understanding of spatial and architectural practices. The book presents seventeen key case studies from a diverse range of perspectives including historical, theoretical, and praxis-based, and range from interrogations of architectural travel and notions of belonging and nationhood to challenging established geopolitical hierarchies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 NEW VISION AND A NEW WORLD ORDER

Great Travel Machines of Sight

Andreas Luescher

O Coração Verde (A Green Heart): Travel, Urban Gardens, and Design of Late Colonial Cities in the Southern Hemisphere

Diane Brand

Nomads and Migrants: Nomads and Migrants: A Comparative Reading of Le Corbusier’s and Sedad Eldem’s Travel Diaries

Esra Akcan

Travel-Writing the Design Industry in Modern Japan, 1910–1925

Sarah Teasley

Learning from Rome

Smilja Milovanović-Bertram

Great Travel Machines of Sight

This chapter offers one mapping of the relationship between travel, space, and architecture using the specific example of the panorama, immense painted landscapes and cityscapes installed in purpose-built rotundas which provided an immersive, 360-degree viewing experience of distant lands and remote occurrences. Particular attention is paid to the role the panorama played in reflecting and shaping perceptions of space during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The panorama’s detailed description of remote places and events fulfilled a fundamental desire for a more comprehensive grasp of the complexities individuals experienced towards the end of the eighteen century, and it successfully satisfied an increasing appetite for visual information spawned by an expansion of travel and the growth of cities. It was the intent of the panorama’s creator, Robert Barker (1739–1806), to offer an illusion of a vast horizon that made objects and actors, near and far, comprehensible as à coup d’oeil.1 Panoramic depictions and their embrace made it necessary to move not only one’s eyes and head in order to grasp the whole, but also one’s body in order to assimilate its vast, continuous canvas.2 As an image that provided sights uncommon or unobtainable in everyday life, the panorama has critical and significant relationships to travel and architecture. Its inherent structural contradictions are what makes the panorama useful as an interpretive tool for rethinking the production of spatial imaginations vis-à-vis travel and architecture. Travel involves both physical and imaginative displacements, experienced through an accumulation of singular and transitory moments which require a contemplative stillness to absorb and reflect upon. Eighteenth-century Western architecture, on the other hand, involved clear physical and imaginative boundaries, and had epitomized stasis. In contrast to it, and analogous to physical mobility and traveling, the panorama successfully simulated the human experience of architecture and urban space that relies on physical and temporal passages through hundreds of successive impressions.

The panorama’s relationship with travel will also be considered through a brief comparison with vedute, a genre of small-scale topographical prospects collected by aristocratic travelers as take-home mementos of their grand tour experiences. Unlike such private, individualized experiences of travel, the panorama popularized a vast number of remote places and historic events to mass audiences and thus had a significant impact on the production of cultural and national imaginations.

Formal and structural implications of panorama’s spatial logic on the production of architecture will be discussed through the work of Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728–99) and Le Corbusier (1887–1965), considering in particular Boullée’s Cenotaph to Isaac Newton, completed in 1784 three years before Barker’s first panorama, and Le Corbusier’s fenêtre en longeur and the Parisian apartment he designed for Charles de Beistegui as celebrations of the non finito.3

BARKER’S PANORAMA

Although the idea of deploying spaces of representation in lived spaces had been expressed in various forms since antiquity, it was not until the mid-1780s in Edinburgh that the mechanics of inscribing an entire 360-degree prospect were settled, and an exhibition of painting on an unprecedented architectural scale was accomplished (WILCOX 1976: 19).4 The late-eighteenth-century cultural milieu of Edinburgh was an extraordinary forcing ground for talent and ingenuity of every type. Largely liberated from the restraining effects of Tory rule, Edinburgh societies fostered the emergence of numerous technical, social and philosophical innovations (STERNBERGER 1977: 39). It was Robert Barker, an Irish portrait painter and teacher of perspective in Scotland during the 1770s and 80s, who fulfilled a generalized ambition to create an image that was not formed within a rectangular boundary but which, just as human vision itself, was unbounded.5 Barker created a high vantage-point painting of the city of Edinburgh on a canvas that literally encircled the viewer. He derived the name of his invention from the Greek word pan meaning ‘all’, and hourama meaning ‘what is seen’. The previous decade had seen numerous antecedents to this scheme. In 1774, English topographical draughtsman Thomas Hearne (1744–1817) produced a sketch of the Lake and Vale of Keswick from Crow Park for the connoisseur and collector Sir George Beaumont (1753–1827), who intended to have the scene painted on the walls of a circular banqueting room. In 1781, the Irish landscapist George Barret (1732–84) painted the walls of a room at William Locke’s Norbury Park in Surrey with a continuous view of the Cumberland Hills (CROFT-MURRAY 1962: 60–66). In the same year, the topographical painter Charles Tomkins (1757–1823) exhibited Circular View of Mount Edgcumbe at the Royal Academy in London. It was also in 1781 that Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740–1812) from Strasbourg first presented his Eidophusikon, in which the principles and techniques of the design of theatrical scenography were applied to a purely scenic entertainment (ALTICK 1978:, 59).6

Barker was not the first to stretch the traditional prospect in order to encompass a full 360 degrees: his originality lay in giving such a view an illusionist presentation on an immense scale.7 The process of gathering and transcribing a 360-degree view onto paper, then rescaling it on a gigantic canvas presented three problems to Barker’s ingenuity: first, recording the scene in situ; second, scaling up and transferring sketches to the full-scale canvas; and third, compensating for surface distortion caused by the extreme weight of the hung canvas in the final painting. The problem of surface distortion was resolved by utilizing optical, not geometric, perspective in an approach was consonant with the reigning romantic preference for the organic over the mechanical (ALTICK 1978: 129). Contemplating the visual field as a whole through analytical and empirical observation was an approach to representation first articulated by Baron Friedrich Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, German naturalist and writer (1769–1859). Humboldt believed that beyond scientific knowledge a harmonious view of nature was accessible only through an emotional experience of its grandeur and sublimity. Disappointed with the state of landscape representation, Humboldt contended that only large-scale scene-painting such is the panorama could succeed in ‘bringing the phenomena of nature generally before the contemplation of the eye and of the mind’ (HUMBOLDT 1850–59: 97). In particular he admired the ‘illusionistic effect of the panorama’ whereby ‘the spectator, enclosed as in a magic circle and withdrawn from all disturbing realities, may the more readily imagine himself surrounded on all sides by nature in another clime’ (1850–59: 98).

After the 1788 public staging of his first panorama in a temporary exhibition structure, Barker built the world’s first panorama building in 1794 at London’s Leicester Square, where it would stand for nearly 70 years as a thriving exhibition hall (HYDE 1988: 17). Barker’s original plan for the building served as the basis for the construction of all other such buildings throughout the nineteenth century. Refinements and elaborations were introduced, but the basic idea of a circular building with enclosures that prevented observers from getting too close to the paintings remained the same. The first panorama rotunda had two exhibition spaces: one large space below that opened with the immense panorama, and a smaller space above.8 Eventually exhibition rotundas appeared as far east as St Petersburg and Moscow, and as far west as North America, where they were known in the nineteenth century as ‘cycloramas’. Already seen panoramic canvases regularly traveled across national and cultural boundaries in exchanged for new ones (HYDE 1988:, 27), fostering spatial imaginations of mass audiences across the world and inciting real travel interest. After its first major exhibition in London in 1788, panoramas enjoyed widespread popularity in Britain and its Empire, Europe and North America through the mid-1800s, and again towards the end of the nineteenth century.

By virtue of their excess, panoramas were liberated from the confusions that beset the more conventional categories of painting in the academia and from the pressures that accompanied avant-garde movements in art. For receptive artists, the unselective nature of a 360-degree painted view may have encouraged greater compositional freedom. Wilcox suggests that Barker may well have sought to match his newly liberated art with an equally liberating approach to subject matter. As Wilcox notes, ‘this was more than a novel amusement; it was a radical transformation of the nature of the painted image’ (1990: 10).9

MOVING PANORAMA

From the time of its introduction in the 1780s, the static nature of the 360-degree stationary panorama had been perceived as a limitation to its success as an illusion. Although the panorama was designed to overcome one of the limitations of traditional painting – that of the static eye – it suffered from the stasis of a painted atmosphere. Of alternative forms of scenic entertainment that arose to compete with the Panorama, the most popular were the moving panorama (peristrephic panorama) which first appeared in London around 1810, and the diorama which first appeared in Paris in 1822 (DUBBINI 1986: 110).

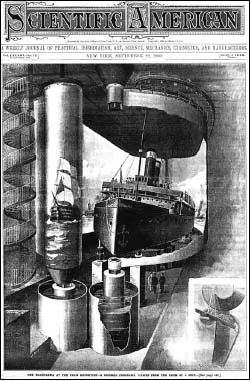

The moving panorama was the invention of another Edinburgh artist, Peter Marshall (1762–1826). The mechanism of the moving panorama was simple: continuously rendered topography painted on long strips of linen or cotton that ran to hundreds or even thousands of feet, stored on large cylinders concealed behind a proscenium-like frame (ALTICK 1978: 199–210). The illusion sought to provide landscape scenery as though perceived from a moving vehicle (such as a boat or a train), or occasionally stage props (such as the wheel of a steamboat attached to the proscenium) to enhance the illusion that it was the viewer and not the painting that was moving (AVERY 1990: 52–8). It was this special conceit that the viewer was riding in a boat, carriage, or train that distinguished moving panorama from the original, and that rendered moving panorama extraordinarily popular in the 1840s and 1850s. The passing scenery implied the passage of time: changes in time of day and weather were normally represented on the canvas and were sometimes enhanced with changes in the intensity and color of light illuminating the picture. The most elaborate panoramas of this genre were those shown at the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris where 21 of the 23 major attractions involved a dynamic illusion of voyage. However, it was the Maréorama which might have been the ultimate peristrephic panorama. Described in a 1900 edition of Scientific American, the Maréorama was a colossal panoramic image which spectators – fully engaged by smoke fumes, steam whistles, and simulated weather – viewed while standing on a hydraulically animated ‘deck’ sandwiched between two simultaneously rolling moving panoramas, each 2,460-feet long and 42.5-feet high (FIGURE 1.1).10 Ultimately however, while these simulations provided the illusion of temporal flow, they could not compete with the environmental simulation of the panorama’s all-encompassing view.

1.1 The Maréorama at the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris. Scientific American, September 1900.

‘TANGIBLE BY THE EYE’

Central to the appreciation of the panorama’s influence on spatial and cultural imagination of mass audiences was the conceptual reframing of the relationship between public imagination with the seemingly boundless world of traveling, and with the dramatic growth of cities. Aristocratic travel since the sixteenth century had been associated with the grand tour, which laid the basis for an enthusiasm for Italian painting and spawned a flourishing international market of guidebooks. An important mid-eighteenth-century development in the language of spatial representation, closely associated with the grand tour, was the Italian veduta, also known as a ‘souvenir views’.11 Like the panorama, the veduta was a painted genre featuring popular views of major cities across Europe, with characteristic buildings and monuments. Unlike the panorama, vedute could be held in the hand like a postcard. The pictorial roots of the vedute were in the topographical tradition of the ‘prospect’, half map and half aerial survey, a motif which thrived in the Netherlands and Italy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and was widespread in Britain during the first half of the eighteenth century (WILCOX 1990: 9). Vedute were uniquely engaging because their steep lines of perspectival recession in an extremely wide oblong format produced the impression that a viewer was immersed in an urban milieu.

By the early nineteenth century, the finite city that had come into being in Europe over the previous 500 years was being transformed by unprecedented migration of populations and the extension of the traditionally walled city into its already burgeoning suburbs (FRAMPTON 1980: 20–21). A consolidating movement characterized by agrarian enclosure policies, rapid urbanization and increasingly aggressive remaining imperial policies produced new and expansive worldviews as well as new cities that could no longer be surveyed by the existing techniques. By the mid-nineteenth century, almost 50 percent of the population of United Kingdom was urban-based, and by the end of the nineteenth century the overall figure was above seventy percent (BUTLIN 1993: 215.) The increasingly complex nineteenth-century urban experience in the world transformed by industry, massive population growth and growing migrations inspired a general desire for the panorama. At the same time, a revolution in the means of traveling was making the world seem smaller: trains and steamers, railroad networks, tunnels, bridges and viaducts did not just alter the face of the landscape (STERNBERGER 1977: 39) but opened the world, the lands, and the seas elaborating thus a new world of unbounded experience. As Jonathan Crary (1990: 39) argued, when optical science shifted the emphasis from geometry to physiology and began studying the mediated relationship between human eye and mind, a distance of one hundred miles no longer implied over a day’s travel for the active traveler-observer who watched space rush past the train window and saw thousands of m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- I Preface

- II For a Theory of Travel in Architectural Studies3

- III Introduction to Travel, Space, Architecture

- 1 New Vision and a New World Order

- 2 Questioning Origins, Searching for Alternatives

- 3 Global Mobilities

- About the Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Travel, Space, Architecture by Miodrag Mitrasinovic, Jilly Traganou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Öffentliche Raumordnung auf lokaler & regionaler Ebene. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.