eBook - ePub

Geographies of Race and Food

Fields, Bodies, Markets

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geographies of Race and Food

Fields, Bodies, Markets

About this book

While interest in the relations of power and identity in food explodes, a hesitancy remains about calling these racial. What difference does race make in the fields where food is grown, the places it is sold and the manner in which it is eaten? How do we understand farming and provisioning, tasting and picking, eating and being eaten, hunger and gardening better by paying attention to race? This collection argues there is an unacknowledged racial dimension to the production and consumption of food under globalization. Building on case studies from across the world, it advances the conceptualization of race by emphasizing embodiment, circulation and materiality, while adding to food advocacy an antiracist perspective it often lacks. Within the three socio-physical spatialities of food - fields, bodies and markets - the collection reveals how race and food are intricately linked. An international and multidisciplinary team of scholars complements each other to shed light on how human groups become entrenched in myriad hierarchies through food, at scales from the dining room and market stall to the slave trade and empire. Following foodways as they constitute racial formations in often surprising ways, the chapters achieve a novel approach to the process of race as one that cannot be reduced to biology, culture or capitalism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geographies of Race and Food by Rachel Slocum, Arun Saldanha, Rachel Slocum,Arun Saldanha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Fields – Ecology, Labor, Inequality

Chapter 3

Fields of Survival, Foods of Memory

Judith Carney

Introduction

Among the celebrated foodways of the Americas are many which evolved in former plantation societies. Hoppin’ John, jambalaya, and gumbo are as emblematic of the US South as the pepper pot stews and bitter greens are of the Caribbean, salt fish and ackee of Jamaica, and the palm-oil flavored dishes and bean fritters of Bahia. However, each is representative of a broader cooking tradition, renowned for inventive combinations of foods, both native and introduced. These fusion cuisines are the product of the meeting in the Americas of the foods of three continents, but there is relatively little attention to the fact that African ingredients give these foodways their distinctive culinary signatures. The accent on rice and bean dishes, okra, collards, sorrel, palm oil, black-eyed and pigeon peas, ackee and other African foods compels serious consideration of the ways these food staples arrived and gained legitimacy in plantation societies. The concern of this chapter is to identify the crucial sites that enabled the diaspora of African foods to plantation tables and the foodways that are part of our common heritage today.

The transatlantic slave trade forced settlement of more than 10 million Africans in the Americas. The trade in turn accelerated a demand for food at a scale unprecedented in global commerce. Slave ships required provisions for lengthy Atlantic crossings. Survival of the enslaved workforce that undergirded the new plantation and mining economies also demanded basic sustenance. A new focus on subsistence draws attention to the slave ship as the conveyor of African foods to the Americas, the food fields of slaves as the nurseries from which these crops propagated, and the role of enslaved Africans in shaping the distinctive foodways of plantation societies.

Slave Food Introductions

A striking feature of the early plantation period is the range of European observers who credit slaves with the introduction of specific foods that we now know are of African origin. Willem Piso, a naturalist who worked in Dutch Brazil in the 1640s, made drawings of the African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum) he found there. Known at that time in English as guinea squash, Piso claimed it was introduced by Angolan slaves. He made similar arguments for okra and sesame (Piso 1957 [1645], 441, 443). His scientific collaborator Georg Marcgraf wrote that the lablab bean ‘was brought from Africa to Brasil’ (Marcgrave 1942, 33). Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum who was in Jamaica from 1687 to 1689, wrote of another legume ‘brought from Africa’ (1707 I: 176) that he described as ‘almost round white Pease something resembling a kidney with a black Eye not so big as the smallest Field pea’ (Carrier 1923, 247). This novel plant, so clearly strange and new to him, is the first certain description of the African cowpea in English America, which became known in the colonies as the black-eyed pea, after its distinctive appearance. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many botanists credited slaves with bringing food to the Americas. English naturalist Mark Catesby attributed enslaved Africans with the introduction of sorghum and millet to the colony (quoted in Carrier 1923, 246).1 French botanist François Richard de Tussac wrote that slaves brought the cytisus (pigeon) pea to the French Antilles. British historian John Oldmixon, referring to an early sixteenth-century account of Hispaniola, contended that yams ‘were brought thither [to Barbados] by the Negroes’ (Oldmixon 1969 [1741] II: 116). Italian botanist Luigi Castiglioni wrote of a plant that ‘was brought by the negroes from the coasts of Africa and is called okra by them’ (Pace 1983, 171–172). Thomas Jefferson claimed that sesame ‘was brought to S. Carolina from Africa by the negroes’ (Betts 1944, 368).

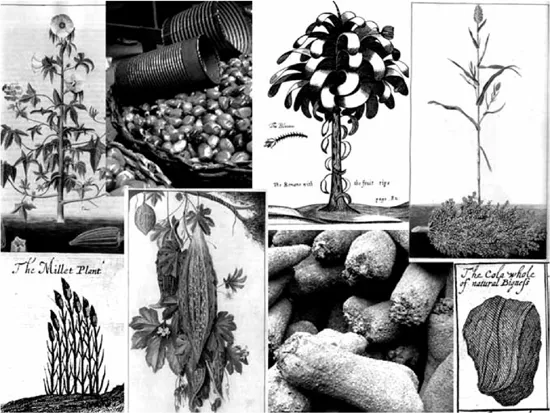

The African foods found in the documents of the plantation period and in the pictorial and archaeological records include: pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), rice (Oryza spp), yams (Dioscorea cayenensis, D. rotundata), black-eyed pea (Vigna unguiculata), pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan), lablab bean (Lablab purpureus), Voandzeia or the Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea), the kola nut (Cola nitida), oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), hibiscus or sorrel (Hibiscus sabdariffa), okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), ackee (Blighia sapida), jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius), cerasee or bitter gourd (Momordica charantia), and guinea squash (Solanum aethiopicum) in addition to some plants of Asian origin that had been grown in Africa for millennia: the banana and plantain (Musa spp.), taro (Colocasia esculenta), and sesame (Sesamum radiatum) (Figure 3.1).

Slaves were also credited with the introduction of the New World peanut, a crop of South American origin that had not reached Mexico in pre-Colombian times (Sauer 1993, 288). Introduced by the Portuguese to Africa before the seventeenth century, the peanut was quickly adopted into existing African food systems. Protected by its shell, it could survive extended sea voyages with minimal spoilage. As the peanut could be eaten either cooked or raw, it quickly became a versatile staple of the Middle Passage. Hans Sloane mentioned its importance as provision on seventeenth-century slave ships to Jamaica: ‘The Fruit, which are call’d by Seamen Earth-Nuts, are brought from Guinea in the Negroes Ships, to feed the Negroes withal in their Voyage from Guinea to Jamaica’ (Sloane 1707 I: 184). The peanut was a novelty to Sloane’s correspondent, naturalist Henry Barham, who used African names (pindalls and gub-a-gubs) to describe the plant he encountered in Jamaica near the end of the seventeenth century:

Figure 3.1 African food and medicinal plants

Note: Clockwise from upper left to lower left: ‘Okra’, by Rev. John Lindsay, 1763, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives; ‘Oil palm nuts’, photograph courtesy of Sybil Azur; ‘Banana’ in Richard Ligon, 1970 [1647] A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes. London: Frank Cass, 82; ‘Sorghum/guinea corn’, by Rev. John Lindsay, 1763, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives; ‘Kola nut’, by Jean Barbot, in Awnsham Churchill, A Collection of Voyages and Travels … London: Printed by assignment from Messieurs Churchill, for T. Osborne, 1752, Vol. V: Plate V, facing p. 107; ‘Yams’, photograph courtesy of Sybil Azur; ‘Cerasse/bitter melon’, by Rev. John Lindsay, 1763, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives; ‘Millet’, by Jean Barbot, in Awnsham Churchill, op. cit., V: Plate 16, p. 200.

The first I ever saw of these [pindalls] growing was in a negro’s plantation, who affirmed, that they grew in great plenty in their country; and they now grow very well in Jamaica. Some call them gub-a-gubs; and others ground-nuts, because the nut of them, or the fruit that is to be eaten, grows in the ground … They may be eaten raw, roasted, or boiled. The oil drawn from them by expression is as good as oil of almonds. (Barham 1794, 145–146)

The cooking and eating practices of the peanut were already diverse in African societies at the time the English discovered them in slave food plots of mainland North America. Prior familiarity with the peanut’s food properties – its multiple uses as nut, oil, confectionary – and the ease of its cultivation contributed to the various African names for it and accelerated its diffusion into English plantation societies.

These commentaries offer insight into what Europeans likely meant when they attributed specific plant introductions to slaves. The Atlantic slave trade demanded reliable supplies of food in order to sustain captives across the Middle Passage, a voyage that typically lasted three to six weeks, sometimes more. The transatlantic slave trade depended vitally on food grown in Africa. Surpluses sold to slavers included indigenous African food staples, Asian tubers that millennia earlier were incorporated into the continent’s food systems, and Amerindian crops (notably maize and the peanut). Indigenous African food staples remained a crucial component of provisions because slave-ship captains commonly believed mortality rates declined if captives were fed foods to which they were accustomed (Falconbridge 1788, 21–22, Conneau 1976, 82, Klein 2004, 220, Searing 1993, 140–141, Davies 1970, 228). New World plantation owners, on the other hand, became acquainted with the African introductions in the food plots of their slaves. It was in these food gardens that botanists discovered their exotic origins.

Slave Ships and the Arrival of African Foods to Plantation Societies

The forced migration of Africans to the Americas involved an almost inconceivable number of transatlantic journeys. While many were never recorded, there is now supporting documentation for more than 35,000 slave voyages from Africa to the Americas (Eltis et al. 2010).2 This number well underscores the enormity of the demand for slave-ship provisions that undoubtedly existed along the West African littoral. A slave ship departing Europe for the African coast brought some food stores, such as salted meat and fish, cheese, biscuits, wheat flour, beer, wine, and horse (fava) beans – intended for the most part for the officers and crew, but also sometimes (in the case of horse beans) for slaves. But the journal entries of ship captains demonstrate the reliance of the transatlantic slave trade on food grown and purchased in Africa (Carney 2001, Carney and Rosomoff 2009). For every ship that boarded African slaves, success ultimately rested on the ability to keep alive a boatload of human beings – often several hundred – for the duration of the Atlantic crossing. This depended on stores of foodstuffs assembled and rationed according to commonly held calculations of daily requirements.

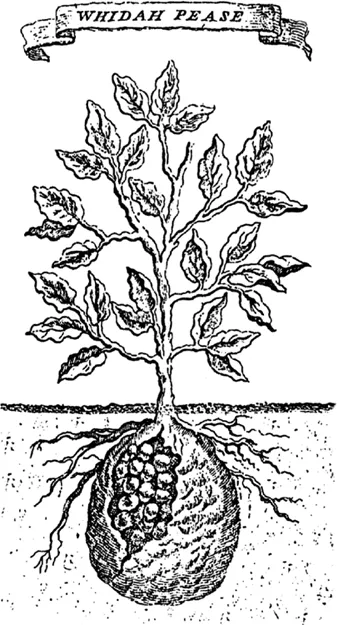

Along the Slave Coast (Nigeria and Benin), James Barbot reported in the seventeenth century that ‘a ship that takes in five hundred slaves, must provide above a hundred thousand yams’. In the same century, slave-ship captains in Angola calculated a ration of about two liters of manioc flour per captive per day plus one-fifth of a liter of African beans, ‘corn’, or flour made from the shell of oil palm nuts (Hair, Jones and Law 1992 II: 699–700, de Alencastro 2000, 252). Some manifests of slave voyages reveal the magnitude of food purchases from African societies. Captain Thomas Phillips purchased five tons of rice in Sierra Leone for his 1693–94 Atlantic crossing. In 1750 John Matthews purchased cowpeas and nearly eight tons of rice for the 200 slaves he carried. Of the 3,000 to 3,500 slaves awaiting shipment from Sierra Leone, Matthews estimated that 700 to 1,000 tons of the grain would be necessary to feed them. For the 250 enslaved Africans the Sandown carried to Jamaica in 1793, Samuel Gamble purchased more than eight tons of rice, cleaned as well as in the husk (Dow 1927, 45, 73, Barry 1998, 118, Donnan I: 393–394, 440, II: 192, 247–269, 279–288, 303–304, III: 61, 158, 293, 373–378, IV: 530, Martin and Spurrell 1962, 20, 27–49, 74–79, Mouser 2002, 337–364, esp. 356, fn 42, Mouser 2002, 45, 86, fn 282, 90, fn 295, 99, fn 317). In the Bight of Benin, yams and plantains were frequently sold as the principal foodstuff. The Diligent purchased at Príncipe one thousand plantains as food for its captives. Slavers also stocked sorghum, millet, maize, cowpeas, pigeon peas, and the small-grained native African cereal, fonio (Digitaria exilis) (Harms 2002, 279–281, Newson and Minchin 2007, 81–82, 320, Rediker 2007, 91, 210, Klein 1999, 94). There is less documentation on minor crops purchased although these were at times illustrated, as one drawing from Dahomey circa 1725 shows. The African ‘peas’ that were boarded on slave ships trafficking with the Ouidah kingdom were simply known as Whidah pease (Figure 3.2).3

Although most slave ships arrived at their New World destinations without surplus foodstuffs, some occasionally did. On a visit aboard an American slave ship that stopped in Barbados, Dr George Pinckard described the captives milling rice – undoubtedly the African species of rice, as the husks were of a red color – with a wooden mortar and pestles (Pinckard, quoted in Dow 1927, xxiii–xxiv). Significantly, the description places unhusked rice grains in the New World after a Middle Passage crossing. Any such grains would retain their potential as seed. The cultivation of tubers and legumes could similarly have begun as leftover victuals on slave ships. Sloane suggested as much in his discussion of the peanut’s appearance in Jamaica.

Such details expose a little discussed topic in the larger scholarship on the Columbian Exchange – the plant and animal transfers that accompanied European maritime expansion between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. The literature ignores a crucial component of the intercontinental species migrations. In this instance, Africa was not only a recipient of biota introduced from other continents but an active contributor. The agents of plant establishment were not European, but African, the migrants were not free but enslaved, and the plant transfers involved species suitable to neotropical environments.

Figure 3.2 ‘Whidah Pease’

Note: Thomas Astley, 1968 [1745–47] A New general Collection of Voyages and Travels Consisting of the Most Esteemed Relations, which have been hitherto published in any Language, 4 vols. London: Frank Cass, Plate 11, p. 57a.

The African species of rice, for example, was among the crops introduced to the Americas on slave ships. It arrived inadvertently – most likely as food remaining from a slave voyage – but its establishment by the enslaved was intentional, as commemorated in the oral histories recounted by descendants of maroon groups (runaway slaves) in South America (Carney 2001, 153–54). Although the Columbian Exchange celebrates the role of New World crops in revolutionizing food systems of Africa, the literature gives scant attention to the similar importance of African food staples in the settlement of the New World tropics, and the possible role of the enslaved in instigating their cultivation for subsistence. In this respect, the African food transfers were unlike any other discussed in the Columbian Exchange literature for they occurred as a consequence of the transatlantic slave trade.

In the Americas, European plantation owners encountered many novel plants in ‘Negro plantations’ – the food fields where slaves were put in charge of their own subsistence. African crops found a New World introduction through the seeds and rootstock occasionally remaining from slave voyages. Critically, their discovery by slaveholders and naturalists as the dietary staples of African slaves, underscores the efforts of the enslaved in instigating their cultivation. These unfamiliar crops, initially encountered in slave food gardens, were in effect those that European naturalists and slaveholders claimed slaves introduced to plantation societies.

The role of slaves in pioneering the cultivation of familiar food staples is additionally illuminated through the names by which African foods became known in the Americas. With no existing nomenclature for many of the plant introductions, naturalists and slaveholders borrowed the African language names used by slaves. In this manner the words yam, banana, okra, gumbo, guando (pigeon pea), bissap (hibiscus), benne (sesame), dendê (palm oil), eddo (taro), bissy (cola), pindar and goober (peanut), and callalou (tropical spinach) entered the vocabulary of colonial languages.

Subsistence and Slave Food Fields

In the initial period of plantation formation white colonizers of tropical America knew little about growing food in the tropics. The principal food that concerned them was sugar, a manifestly profitable commodity that necessitated apprenticeship for growers eager to learn its proper cultivation and processing methods. With their attention and energies focused on commodity production, European settlers in the New World tropics for the most part left the crucial matter of producing food to their slaves. There was reason for this. The peoples that the colonizers subjugated – initially Amerindian, then African – were for the most part already expert tropical farmers. Tropical agriculture relies on an entirely different arra...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Geographies of Race and Food: An Introduction

- 2 Race in the Study of Food1

- Part I Fields – Ecology, Labor, Inequality

- Part II Bodies – Diet, Taste, Biopolitics

- Part III Markets – Exchange, Commodification, Empire

- Index