- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The museum today faces complex questions of definition, representation, ethics, aspiration and economic survival. Alongside this we see burgeoning use of an array of new media including increasingly dynamic web portals and content, digital archives, social networks, blogs and online games. At the heart of this are changes to the idea of 'visitor' and 'audience' and their participation and representation in the new cultural sphere. This insightful book unpacks a number of contradictions that help to frame and articulate digital media work in the museum and questions what constitutes authentic participation. Based on original empirical research and a range of case studies the author explores questions about the museum as media from a number of different disciplines and shows that across museums and the study of them, the cultural logic is changing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Museums in the New Mediascape by Jenny Kidd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Museum Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Transmedia Museum

An artistic movement, albeit an organic and as-yet-unstated one is forming. What are its key components? A deliberate unartiness: ‘raw’ material, seemingly unprocessed, unfiltered, uncensored, and unprofessional. (What, in the last half century, has been more influential than Abraham Zapruder’s 8-mm film of the Kennedy assassination?) Randomness, openness to accident and serendipity, spontaneity; artistic risk, emotional urgency and intensity, reader/viewer participation … plasticity of form, pointillism, criticism as autobiography; self-reflexivity, self-ethnography, anthropological autobiography, a blurring (to the point of invisibility) of any distinction between fiction and nonfiction: The lure and blur of the real. (Shields 2010: 5)

The book begins with a provocation on the future of museum narratives in a world where media are becoming pervasive, ubiquitous and storified. As David Shields asserts, this is a landscape where reality and engagement with form and content are being redefined and re-imagined. It is landscape where increasingly the museum cannot be contained within walls or within dedicated websites; where visitors ‘read’ and interpret the museum at the same time as the museum ‘reads’ and interprets the visitor (for example through their ‘data’ and demographics); where the notion of a comprehensive, complete and ‘satisfying’ museum encounter begins to lose its appeal in favour of museum experiences that challenge, fragment and spill over into the everyday; and where the museum as a storyteller and maker is itself foregrounded and problematised. This chapter uses the notion of transmedia to try to understand these changes.

Transmedia storytelling broadly relates to the extension of narrative across multiple platforms, and the implication of a ‘user’ in calling that narrative forth from a multitude of entry points – in diverse spaces and in varying states of ‘completion’. It is proposed in this chapter that the museum, and historical narratives more broadly, might be easily understood as (already often) transmediated. The stories museums tell – through exhibitions and their associated interactions, performances, workshops, online web portals and micro-sites; social networks, digital archives and games – create webs of engagements and interactions which are variously and incompletely accessed in the decoding, or indeed creation, of meaning by users.

This chapter seeks to explore what the implications of understanding the museum as a transmedia text might be. It is not my intention to suggest that this is a dramatic new way of presenting the museum ‘text’. Rather, I seek to render transmediation a visible, and consequently more active, articulation and manifestation of practice.

The chapter offers a definition and discussion of transmedia, and an overview of its potential use-value in museum contexts, before going on to present four characteristics that may be of use here. I wish not to present a distinct taxonomy, seeing such a thing as incongruous with the realities of transmedial practices. Rather, the characteristics present a means of exploring what is currently happening in the realm of museum media, and offering a language for extending into more radical conceptions of such modes of interaction in the future. They are both preliminary and extensible.

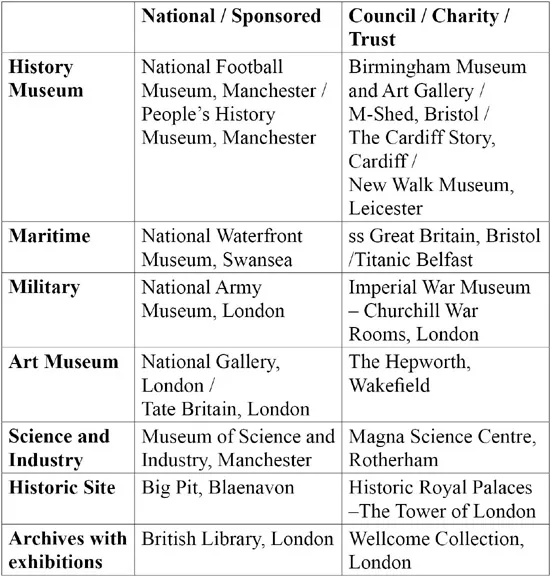

Table 1.1 Sites in the sample

These characteristics have emerged from a detailed study of the various outputs (online and offline) of 20 museums in the UK. This focus on the United Kingdom has been necessary in order to allow for site visits and repeat visits. The sample for analysis has been chosen to exemplify (not represent) a number of broad distinctions in museum typology, and with a view to representing both national museums and smaller regional and commercial ventures (see Table 1.1).

Observations from site visits and associated media (including interactives, audio-visual presentations, performances and audio guides) were gathered, alongside a detailed audit and content analysis of various online outputs. These included the institutions’ current website offerings (general information, digital archives, interactives, education pages, policy documentation), apps, social media content (more in Chapter 2), memes and contributions to larger initiatives such as Google Art project1 and Europeana.2 In sum, a detailed and robust representation of each site and its mediation was analysed.

The initial intention was to explore the relationship between online and on-site content, with a working hypothesis that these distinctions were beginning to collapse, ceasing to be meaningful as the boundaries of both become more porous (Dicks 2003, Farman 2012). This may well be true, but in the analysis the online–offline framework proved reductionist in the extreme. A more elaborate picture emerged, one that required a holistic and more thorough appraisal of each of the cases, and the adoption of a new theoretical model to account for their subtleties and peculiarities. It is my contention that ‘transmedia’ allows for this as a far more nuanced framework than the online–offline distinction.

Defining Transmedia

The noted communications scholar Henry Jenkins is credited with recognising and categorising what were then emergent modes of cross-platform storytelling as ‘transmedia’, proposing that some narratives are ‘so large’ they ‘cannot be covered in a single medium’ (Jenkins 2006: 95).3 Similarly, to Pratten, telling stories across multiple media works ‘because no single media satisfies our curiosity or our lifestyle’ (Pratten 2011: 3).4

Using multiple media platforms simultaneously, transmedia storytelling thus allows for differing entry points for audiences; varying and contrasting perspectives on the action to be offered; and, crucially, opens up opportunities for play. In this conception, narratives can be fruitfully and engagingly told through continuation, experience and participation, relaxing the boundaries between online and offline, audience and producer, even truth and fiction. Such narratives, although to a point constructed, implicate the audience in their telling – challenging them, acknowledging and problematising their agency and making them work in order to piece together meaning. To Jenkins, ‘dispersal’, ‘agency’ and cross-fertilisation are at the heart of transmedia activity (2010). What we are left with is ‘a diversity of media complicating and complimenting one another’ (Clarke 2013: 209).

These are ‘emergent forms of storytelling which tap into the flow of content across media and the networking of fan response’ (Jenkins 2011). In its utilisation in the traditional media landscape, transmedia has most often been used as a way of offering or filling in a film or television series’ backstory: mapping complex narrative universes (through for example multiple fictional websites); offering additional character’s perspectives on the story (through, say, their blogs or Twitter feeds); and deepening audience engagement through various means (Jenkins 2011). Transmedia has also been seen as a way of building communities around content: communities interested in ‘cognitive investment’, experimentation and play (Ryan 2013).5

This is a notion of storytelling that has gained ground in recent years in talk about distributed narratives (Walker 2004), deep media (Rose 2011), networked narrative (Zapp 2004) and transmedia practice (Dena 2009).6 Jenkins has taken some issue with the ways in which his idea of transmedia storytelling has been applied (perhaps most problematically as branding and marketing activity), but has in recent years sought to apply it in differing contexts himself: to politics, in overviewing the Obama campaign (Jenkins 2009); and perhaps most notably for us in his discussion of transmedia education (2010). In this context:

students need to actively seek out content through a hunting and gathering process which leads them across multiple media platforms. Students have to decide whether what they find belongs to the same story and world as other elements. They have to weigh the reliability of information that emerges in different contexts. No two people will find the same content and so they end up needing to compare notes and pool knowledge with others. (Jenkins 2010)

I want to suggest that this mode of enquiry, sociality and play might be increasingly characterising engagement in the mediated museum, and that notions of transmedia could help us understand how best museum narratives are being constructed, accessed and experienced in the twenty-first century museum. I wish not to suggest that this is a purely digital phenomenon; indeed, there have been museum exhibitions that we might conceive of as transmedial in previous manifestations of the museum. Rather, this chapter explores the ways in which that trend is magnified in the ‘connected’ museum and how, increasingly, visitors come with expectations of the museum as embedded and implicated in historical and institutional narratives that implicate, and go beyond, the institutions that they knowingly visit either virtually or physically. I suggest that ‘radical intertextuality and multimodality for the purposes of additive comprehension’ (Jenkins 2011), so important in transmedia storytelling, are fast becoming the norm in the museum where ‘the story we construct depends on which media extensions we draw upon’ (Jenkins 2011; see also Voigts and Nicklas 2013: 141).

Jenkins’ concept of transmedia utilises seven core concepts that inform the analysis and discussion in this chapter: Spreadability/Drillability, or the boundless capacity for building content across a landscape, and people’s ability to drill ever deeper and deeper into that content; Continuity/Multiplicity, or the use of and adherence to a canon versus the capacity of media to tell multiple versions of stories from differing perspectives; Immersion/Extractability, or the ability of audiences to immerse themselves in narratives, but then to extract elements of it that inspire and ‘deploy’ them in the everyday spaces of their lives; Worldbuilding, the capacity of multiple media to extend narratives into whole worlds of enquiry; Seriality, the ‘meaningful chunking and dispersal’ of narrative into multiple, perhaps infinite, discrete chunks; Subjectivity, seeing through new eyes and ‘breaking out of historical biases’ and then being implicated in the telling; and, lastly, creating a part for themselves in the narrative through Performance. Here, the audience becomes ‘visibly present and identifiable in the universe of the tale’ (Giovagnoli 2011: 18) at the same time as the author/creator loses their visibility ‘in order to consider – from the beginning – the WHAT and HOW of the tale as a function of the audience, more than the creator’ (Giovagnoli 2011: 19). According to Jenkins, the public act as ‘hunters and gatherers, chasing down bits of the story across media channels’ (Jenkins 2006: 21). This, I contend, is something the museum visitor already does, and heritage ‘makers’ could more creatively and readily acknowledge.

As has been noted in the Introduction, it is recognised that the museum visit is increasingly a mediated one: ‘connected’, ‘networked’ and ‘participatory’. Consequently, the boundaries of the museum visit become unclear. When does a museum visit start? When, indeed, does it stop? (Samis 2008: 3). How do visitors distinguish between the different forms of information that they ‘consume’ on a visit (whether online or offline), the different voices that they find therein, or the different modes of address: the official and authoritative, the playful, or the voices of the other visitors? How do visitors conceive of themselves as implicated in the museum narrative: when posting their photos during a visit or when pinning a piece of content for later? How do search engines, museum websites, performances on site, interactive exhibits or artworks, QR codes, apps, the exhibition catalogue, the site map or the museum shop and its wares help to construct or complicate the narrative of a visit? Jason Farman notes that ‘locating one’s self simultaneously in digital space and in material space has become an everyday action for many people (Farman 2012: 17). So are visitors even conscious of those distinctions?

This is an area of museum enquiry that has gathered pace in recent years, but we still have very little understanding of how the museum experience, and museum-facilitated learning, operates within and across the different constituencies of the museum. As Lynda Kelly asks, ‘How are museums relating the physical objects on display with deep, rich information available across a range of online platforms, including mobile?’ (Kelly 2013: 62–3). Indeed, this nod to the physicality of the museum and its collections reminds us also to look at the visit as a bodily practice, as Helen Rees Leahy notes:

the eye of the practised museum spectator is always embodied within a repertoire of actions that reflect and respond to the space of display, the conditions of viewing and the presence of other spectators. (Rees Leahy 2012: 3–4)

We might ask, how can the online visit similarly be understood as embodied?78

It is in consideration of such questions that the notion of transmedia, with its understanding of the visitor as hunter-gatherer, becomes so seductive, not least because it accords with recent conceptions of museum learning as constructivist, inquiry-led, lifelong, contextual and often informal. In 2008, John Falk and Lynn Dierking, eminent scholars in the fields of visitor studies and museum learning, appraised their findings about visitor expectations as follows: firstly, that ‘the best museum is the one that presents a variety of interesting material and experiences that appeal to different age groups, educational levels, personal interests, and technical levels’; secondly, they noted that ‘visitors expect to be mentally, and perhaps physically, engaged in some way by what they see and do … they expect to be able to personally connect in some way with the objects, ideas, and experiences provided’; thirdly, that visitors ‘expect to enjoy a shared experience, as the members of the group with their varying interests and backgrounds collaborate and converse together’ (Falk and Dierking 2008). In this assessment, ‘the best’ on-site museum experiences emerge as embodied, immersive, social, inquisitive, collaborative, challenging and experiential. They utilise a variety of media, at different levels, with varying entry points. In short, Falk and Dierking go some way towards envisaging the transmedia museum.

What Is a Museum Narrative?

In the 2008 Center for the Future of Museums report, which projects into the 2030s to imagine the museum of the future, the authors assert that ‘For most adults over the age of 30, “narrative” is a passive experience … For Americans under 30, there’s an emerging structural shift in which consumers increasingly drive narrative’ (CFM 2008: 17). They go on to predict that ‘Over time, museum audiences are likely to expect to be part of the narrative experience at museums’ (CFM 2008: 18). I don’t disagree with these bold and far-reaching statements, but they do demand closer scrutiny.

The previous discussion of transmedia made use of literature that has been produced almost exclusively to elucidate emerging practice in the realm of the fictive arts, including but not limited to television series, computer games and big-budget films. Yet I maintain they are a useful way of thinking about the ‘narratives’ produced across museum sites: the stories they tell about pasts, communities, nation, place, individuals, identity and our potential futures, but also about the more mundane and technical aspects of our lives. I wish not to contend that museums are in the business of presenting grand narratives of truth about the world, Message’s ‘monumentalizing narrative’ (2006: 28), believing we have moved far beyond such a conception of the museum. Rather, I hold that museum narratives are multiple, incongruous and overlapping, far from ready-made, complete or perfect, and that they are accessed variously and partially in a number of locations.

This is not so contentious if one looks at the literature emerging, increasingly in recent years, which indicates a creeping recognition of a narrative turn in the museum (Kelly 2010b, Rowe et al. 2002, Chan 2012, Henning 2006, Ross 2013). Ross Parry notes that ‘museums have tended to resist a fictive tradition that has been a strong part of their (pre-web) history’ (2013a: 18). He goes on to assert that:

This is a fictive tradition of using artifice (alongside the original), the illusory (amidst the evidenced), and make-believe (betwixt the authenticated). These are the well-established curatorial techniques of imitation (showing and using copies), illustration (conveying ideas without objects), immersion (framing concepts in theatrical and performative ways), and irony (speaking...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: On Museum Media

- 1 The Transmedia Museum

- 2 Museum Communications in Social Networks

- 3 User-Created Content

- 4 Democratising Narratives: Or, The Accumulation of the Digital Memory Archive

- 5 ‘Interactives’ in the Social Museum

- 6 Museum Online Games as Empathetic Encounters

- 7 Mashup the Museum

- Bibliography

- Index