![]()

Part I

The impact of Cohesion Policy

![]()

1 The long-term effectiveness of EU Cohesion Policy

Assessing the achievements of the ERDF, 1989–2012

John Bachtler, Iain Begg, David Charles and Laura Polverari

Introduction

One of the major challenges for EU Cohesion Policy is that, after 25 years of implementing the policy, the evidence for its effectiveness is so inconclusive. Academic research and evaluation studies have reached widely differing conclusions on the results of interventions through Structural and Cohesion Funds (Bachtler and Gorzelak, 2007; Polverari and Bachtler, 2014). At the same time, political and public debate on the performance of the policy has increased, most evident in the discussions on the reforms of Cohesion Policy for the 2007–13 and 2014–20 periods and the pressure on EU and national policymakers to improve performance. This give rise to several questions: is it correct that substantial Cohesion Policy resources have been spent without adequate strategic justification? If so, why has this been the case? And will the new reforms make a difference?

The following chapter seeks to answer these questions based on an evaluation of the main achievements of Cohesion Policy programmes and projects over the longer term. Drawing on research undertaken in 15 selected regions of the EU15, it is the first longitudinal and comparative analysis of the implementation of the Funds from 1989 to 2012, covering almost four full programme periods. Specifically, it involved analysis of the relevance, effectiveness and utility of each of the Cohesion Policy programmes implemented in each of the regions. In assessing the achievements of the programmes, the study adopted a ‘theory-based evaluation’ approach, going beyond the formally stated objectives of programmes to uncover the mechanisms or theories of change underlying the design of programmes, as well as identifying the ways in which objectives were actually operationalised in practice (Bachtler et al., 2013b).1

The chapter begins by outlining the context for the research and the methodology. It then discusses the nature of the strategies implemented over the 1989–2012 period, their relevance to the regional development situation of the 15 regions and the expenditure committed over time and to different themes. The chapter then focuses on the assessment of the achievements of the programmes, and their effectiveness and utility, before drawing together the main conclusions to emerge from the study.

Context

Cohesion Policy has been subject to more extensive evaluation at EU, national and sub-national levels than any other area of EU policy. Successive reforms of the Funds since 1988 have progressively increased the obligations on the European Commission (EC) and member state authorities to undertake systematic evaluations of interventions ex ante, during programme implementation and ex post. The EU budgetary debates since the late 1990s have also been conducted against a background of net payer efforts to limit the growth of the EU budget and redirect spending away from Cohesion Policy and the CAP to so-called ‘competitiveness policies’ such as R&D, pressures that were intensified by the Lisbon Strategy and Europe 2020 (Bachtler et al., 2013a). This has forced the EC to justify the resources and effectiveness of Cohesion Policy to a greater degree, reflected in greater attention being given to the evaluation of the policy and its performance in preparing the reforms for the 2014–20 period and ultimately the new regulatory framework.

A range of methodological approaches have been used to analyse the effectiveness, impact and added value of Cohesion Policy funding – principally macroeconomic models, regression analysis, micro-economic studies and qualitative case studies. While each has strengths and weaknesses, all of the methods involve difficulties associated with the poor availability of regional data on socio-economic indicators and spending, and the problem of comparing outcomes with a counterfactual, and there is little consistency in the findings (Davies, 2014). Overall, therefore, it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions from the studies on the scale of impacts, or on the factors that condition the effectiveness of Cohesion Policy funding across member states and regions.

Methodology

Against this background, the distinctive methodological approach adopted for this study was an experimental ‘theory-based evaluation’. Its essence is to assess whether the programmes implemented by the regions achieved what they were designed to do and whether what they achieved dealt with the needs of the region (as identified at the start of the process) (Hart, 2007; Leeuw, 2012). This methodology does not try to establish a direct causal link between the Cohesion Policy interventions and changes in standard macroeconomic variables at the regional level, such as GDP per capita or the unemployment rate. The focus of theory-based evaluation (as interpreted for this study) is on understanding what it was that policymakers sought to change, and how what was done was expected to influence regional development. It addresses the logic behind the policy interventions, whether such logic was appropriate for the specific regional circumstances, and how policy evolved as initial needs were met and new ones had to be confronted.

The objectives of the study were twofold. First, it sought to examine the achievements of all regional programmes and regionally implemented national programmes co-financed by the ERDF and, where applicable, the Cohesion Fund, that have been implemented in the 15 selected regions from 1989 to 2012. Second, it aimed to assess the relevance of programmes and the effectiveness and utility of programme achievements.

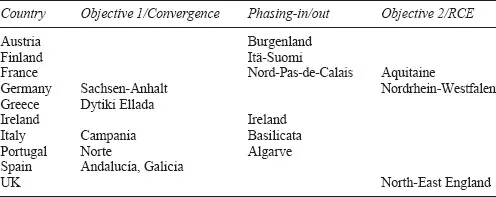

The core of the research involved 15 regional case studies conducted in three types of region (see Table 1.1):

1 six regions eligible for Objective 1/Convergence support from 1989–93 to the present;

2 six regions eligible for Objective 1 or 6 support at one time, but with Phasing-in/-out or Regional Competitiveness & Employment (RCE) status in 2007–13;

3 three regions partially or wholly eligible for Objective 2/RCE status from 1989–93 to 2012.

Research was carried out in each of the regions, using a mix of desk research, online and fieldwork interview surveys with a wide range of respondents and consultative workshops. A central thread of the analysis was the use of eight ‘thematic axes’ (or themes) as a framework for analysing the programmes’ achievements:

1 innovation

2 enterprise

3 structural adjustment

4 infrastructure

5 environment

6 labour market

7 social cohesion

8 territorial cohesion.

Table 1.1 Case study regions.

Regional needs and the relevance of strategies

At the end of the 1980s, each of the 15 case study regions faced particular challenges, reflecting their geographical situation and historical background. The three main types of needs were categorised as:

1 major underdevelopment and indicators of disadvantage ranging from a lack of basic infrastructure and services, to skills deficits, often compounded by peripherality or significant internal disparities (Dytiki Ellada, Campania, Norte, Andalucía, Basilicata, Algarve and Ireland);

2 restructuring in regions facing either transition from a centrally planned economy (Sachsen-Anhalt) or from an economy dominated by large, declining traditional industries (Nordrhein-Westfalen, Nord-Pas-de-Calais and North-East England);

3 agricultural modernisation and economic diversification in predominantly rural or peripheral regions (mainly Aquitaine, Burgenland, Itä-Suomi and Galicia).

All of the case study regions were at a relative disadvantage at the start of the period, having significantly lower levels of development relative to either national or EU averages, but with significant differences within the group. Up to 2008, most regions performed worse than the EU average in GVA growth over the period. Only Ireland demonstrated a clear virtuous cycle of above-average performance for both output productivity and employment. Others saw some growth based on increased employment or improved productivity, but most struggled to outperform the EU average. Since 2008, many of the regions have seen poorer performance as a result of the recession.

The early ERDF programmes of the case study regions had relatively basic, generic strategies, often with limited assessment of needs; they tried to encompass diverse stakeholder interests with objectives and priorities that were open to interpretation. Initially, there was little pressure to change, and many strategies were remarkably stable during the 1990s. However, programming for 2000–6 saw substantial strategic reassessments in several regions and even more so for 2007–13, driven by the Community Strategic Guidelines or changes in eligibility status.

The conceptual basis for programmes was often weak. Throughout the period since 1989, strategies were not underpinned explicitly by theory or development models, but rather by prevailing assumptions of economic development. Nevertheless, the research found that all of the programmes were at least partially relevant to regional needs (in certain periods or for parts of the programmes), and almost half of the programmes were relevant across the whole period from 1989 to 2012. The main thematic trends over time are a greater emphasis on R&D and innovation, more support for entrepreneurship and more sophisticated SME interventions, the mainstreaming of urban regeneration and a specific focus on community development.

In the early periods (1989–93 and 1994–9), programme objectives were generally neither specific nor measurable due to a lack of quantified targets and non-existent or inadequate monitoring systems. The attainability of objectives was also questionable; strategies were mostly overambitious and did not recognise the limited potential contribution of the ERDF programmes in the wider economic and policy contexts. Even if quantified, programme targets often required adjustments during the programme period. However, the vagueness of objectives allowed managing authorities to report ‘success’ or interpret effectiveness in different ways. Programme objectives were usually not timely, in the sense that the achievement of objectives was likely to take much longer than the programme period – a factor that was not always acknowledged. The ‘SMART’ character of programme objectives improved over time, but by 2012 they were still some way from being fully achieved, either because of deficiencies in programme design or delays and difficulties with the operationalisation of monitoring systems.

How much was spent? Programme expenditure, 1989–2012

Analysing trends in the expenditure of Structural and Cohesion Funds over time and across regions has traditionally been problematic. Multiple sources, inconsistent reporting and delays in closing programmes and finalising expenditure have presented major challenges for comparative research. It was only in the 2007–13 period that the EC was able to introduce a structured, systematic approach to member states’ reporting on the financial progress of programmes. This study, therefore, had to undertake primary research based on a bottom-up classification and aggregation of measure-level expenditure information, undertaken for each of the 15 regions.

Over the period from 1989 to 2012, more than €146 billion of Structural and Cohesion Funds was estimated to have been spent in the 15 regions (see Figure 1.1). The Objective 1/Convergence regions had the largest share, of 68.3 per cent (c.€99.6 billion), with Phasing-in/-out and Objective 2/RCE regions representing a more modest 21.6 per cent (c.€31.5 billion) and 10.1 per cent (c.€14.7 billion) respectively. Across the entire period, allocations exceeded expenditure by c.€14 billion (c.9 per cent of the initial allocation). This figure should however be interpreted with great caution given that, especially for early periods, it was not always possible to reconstruct the non-earmarked regional allocations of the National Operational Programmes (N...