- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultures of Glass Architecture

About this book

When designing, architects are responding to and creating a relationship between identity, culture and architectural style. This book discusses whether the extent of the use of glass facades has increased, or indeed enhanced, the creation of meaningful place-making, thereby creating a cultural identity of 'place'. Looking at the development of perceptions of glass facades in different cultures, it shows how modernist 'glass' buildings are perceived as an expression of technical achievement, as symbols of global economic success and as setting a neutral platform for multi-cultural societies - all of which are difficult for urban developers and policy makers to resist in our era of globalization. Drawing on a number of modern and heritage design projects from Europe, the USA, the Middle East and South East Asia, the book reviews efforts of some regional towns and local places to move up the economic ladder by adopting a more 'global' aesthetic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultures of Glass Architecture by Hisham Elkadi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Essays & Monographs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture Essays & MonographsChapter 1

Glassworks: The History of Glass and its Architectural Identity

Introduction

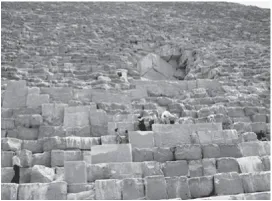

Noever (1991: 8) argued that the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt (2723 BC) could be considered the ultimate expression of architecture because it manifests an idea in a functionally pure form (Figure 1.1). In the pyramid’s case, a sandstone block provides an indication of the qualities of accuracy and geometric precision; it creates a form, serves a function and expresses an idea. The Pyramid of Cheops also has a definite identity with its place and its surroundings. These are the phenomena that give this piece of architecture its greatness. Both its unity with nature and the geometric precision of its cardinal axis help to create its uniqueness. The siting in relation to the Nile, the internal shafts meant to symbolize the passage of the soul to convene with the stars’ eternal life, and the geometric reference to the life-death cycles of the east-west axis of the Nile are just three examples of the Great Pyramid’s strong environmental links. What remains in our memories, however, is the strong visual representation of its façade. Façades, the architectural representations of cultures, are key ingredients in creating a visual identity of a place.

1.1 The Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt (2723 BC)

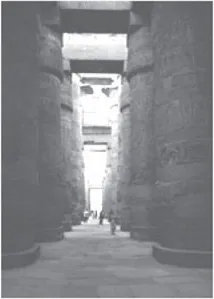

A façade is defined in the Oxford dictionary as ‘the face of a building’. A façade both obscures and protects a building’s core. Openings and windows give a façade its distinctiveness. Windows preceded the development of glass by several centuries; they were part of the architectural aesthetics of buildings during the Fourth Dynasty in Egypt. An example can be seen in the openings in the pyramid of Dahshur (2723 BC). More elaborate windows were found in the temple of Ramses II in Medinet Habu (1198 BC) and in the Hypostyle Hall in Karnak (1198 BC) (Figure 1.2). These windows were used not only to provide lighting and ventilation but also as part of a deliberate playing with light and shadows to accentuate processions within the temples.

1.2 A window in Karnak Temple, Luxor (1198 BC)

The Birth of Glass

From its discovery in the eastern Mediterranean in the middle of the thirteenth century BC, glass has basically been made of silicon dioxide (SiO2 or silica), with soda added as a flux to facilitate the melting of the batch and lime as a stabilizer against the adverse effects of water. Unlike other materials which are formed through the melting of batches, glass retains the ambiguity of the random molecular structure of liquids rather than the crystallized structure of metals. It was not until the seventeenth century that the development of lead glass made a major step forward in the know-how of glassmaking. This invention was to enable the glazing of large windows (de conjungendis et solidandis fenestris), a technology that brought glass into the history of architecture. Examination of ancient pieces revealed that four main manufacturing methods were standard; rod and core forming, casting with open and closed moulds, free blowing, and blowing into moulds and forms. Colouring of glass, through the addition of metallic oxides, had already been perfected by ancient workers, most often using copper, manganese or cobalt.

1.3 Transparent goblets of crystal from Saqqara, Egypt (2000 BC)

The phenomenon of transparency has always captured the imagination of people. Sophisticated transparent goblets of rock crystal were found in Egypt as early as the First Dynasty in the tomb of Hamaka, Saqqara (Figure 1.3). Little is known about glassworking in its earliest period. The legend of the glass palace and Solomon’s throne on reflective surfaces in the story of the Queen of Sheba is well known in the Jewish and Arabic traditions, but no evidence exists of whether the reflection quoted in the story was actually a result of a glass surface or of other crystalline rocks. The legend, however, is a further indication of early fascination with the phenomena of reflections and the transparency of materials, both of which capture human imagination. In the Bronze Age, the glass vessels of the prolific Egyptian industry are early examples that reflect sophistication. Factories located in Tel el Amarnah were productive well before 1450 BC. Some of the vessels found in the area have the cartouche of Thutmos III who ruled during that time. Other glass items were also found in other parts of the eastern Mediterranean including Syria, Cyprus and Southern Greece. While most of these products resemble Egyptian imports, there are many that reflect the uniqueness of their particular locales. It is believed that, because of the westward migration of some glass workers, glass artefacts started to appear in areas such as Yugoslavia and Southern Austria by the seventh century BC. By the fourth century BC, glass was widely manufactured in many parts of the eastern Mediterranean. Glass beads and glass vessels were also found in Iran, where a flourishing Persian glass industry produced cast and cut bowls in colourless or greenish glass. The Hellenistic period also witnessed surges in the glass industry in the major settlements around the eastern Mediterranean coast, including Alexandria, Sidon, and settlements on the Palestine and Syrian coasts, as well as in Greece and Italy. Alexander the Great founded the famous glassworks in Alexandria in 332 BC. Glass in this period represented an indication of the vast trade among different parts of the eastern Mediterranean and a proof of the flourishing common culture in this part of the world. Until this period, there is no evidence to suggest that glass was used in architecture and buildings. The mild climate of the eastern Mediterranean did not necessitate the use of material to protect the interiors either from excessive heat or extreme cold. Writers, however, hinted at the creation of artificial environments, but such environments (such as the gardens of Adonis) were limited to the protection of plants in the fifth century BC (Hix 1996).

At that time, glass was not thought to contribute to this idea of an artificial environment. Even during the first century, when practical measures were taken to create ‘greenhouses’ for plants, transparent stone (lapis specularis or mica) is thought to have been used. The discovery of how to blow glass in the first century BC was a major step forward. Wigginton (1996) considered this discovery to be the first important step in the development of glass in architecture. This major development probably took place in Sidon (Thorpe 1949). The trade was kept within Syrian families, who made use of the advantages of the Roman Empire to export their precious goods. The willingness of such families to migrate enabled the establishment of their industrial enclaves in many cities around the Mediterranean. One of the reasons for the scant documentation and description of glass technology at its early production was the strong protection by the producers and traders of their know-how. Later in Venice, protection was at royal and aristocratic level: the licence to allow a glassmaker to work on some important project abroad was often an item negotiated by a king himself.

Glass Cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean

The harmonious material culture continued in the eastern Mediterranean during the Roman period. The stability and the extent of the Empire encouraged the flourishing of arts and crafts and extended the glass industry’s scale and horizon: Charleston referred to this period as a new age for glass (Charleston 1984: 22). The mould-blowing technique appeared in 25 AD and led to large-scale production of affordable glass vessels, and, by the mid-century, glass became a common material for tableware, beads and other uses. The phenomenon and the novelty of transparency were introduced to the common citizens of the Empire in 40 AD, with the manufacturing of colourless glass. In this period, glass was introduced to architecture. The first windowpanes were mounted in wooden or metal frames during the Augustan Age. They were used, for example, to glaze windows or screens at the Atreum Vestae, the sacred building of the six Vestal Virgins. The development of new building typology such as baths (with their need to retain heat) had also necessitated the use of glass during this time. Wigginton (1999) indicates that glass windows with pieces as large as 1 metre × 700 mm have been found in one of the baths in Pompeii. Other uses of glass were mainly in residential settings, especially in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Coloured glass was also used for decoration in buildings on walls, floors and ceilings, both in private and public buildings. An early example from a Coptic Egypt setting is the upper part of a mosaic wall that has cut pieces of coloured glass with Christian motifs. This technique was mastered and used to embellish architecture during the Byzantine period. Small glass pieces for mosaic (tesserae) continued to be made in Rome and Alexandria to decorate walls, ceilings and floors in Byzantine churches. The second and third centuries AD witnessed a variety of experimentation and the production of different types of glass, including white opaque glass, the ornamentation of vessels and deliberately coloured glass pieces.

The turmoil and difficulties that faced the Romans in the third century AD affected the glass industry in two ways and (surprisingly) contributed positively to the use of glass in architecture. Firstly, the social transformation and the acceptance of Christianity as the imperial religion led to a dramatic shift towards simplification in the decoration of daily-use glass vessels and more focus on religious buildings. Secondly, the relative disintegration of the Empire led to an increase in the disparate regional and local styles of design.

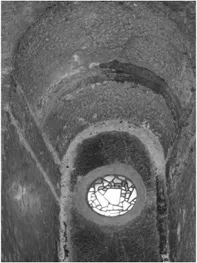

The fall of the Roman Empire led to distinct glass practices in the north and south of Europe. Glassworks in Germany continued under the rule of the Franks. The most famous contribution was the development of the claw decoration technique, which was added to the already-developed cone beakers and drinking horns. While the Christian Church prohibited the use of glass chalices in AD 803, manufacturing of glass continued for day-to-day vessels. Development of techniques was, however, confined to architectural use. During this period, glassmakers were confined to monasteries, the new centres of wealth in northern Europe, and were encouraged to produce stained glass for the windows of their abbeys. Several monasteries’ records from the ninth and tenth century refer to a ‘Fra Vitrearius’, who would be in charge of the monastery’s glass. France was the main centre of production and there was a French connection with the monastic foundations at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria in the north-east of England. Excavations at Jarrow have yielded much information about the use of glass at this period (Figure 1.4). French glassmakers set up glasshouses in Northumbria in AD 676. The abbot of Jarrow continued, however, to ask for help with glassmaking from other sources – one was Archbishop Lullus of Mainz in the Rhineland (AD 758).

1.4 Excavations at Jarrow, Tyne and Wear (AD 676)

Further south, in Spain in the same period, the glass industry flourished in the advanced Moorish-Islamic culture. The technique of lustre painting, using metals dissolved in acid which were painted on cold glass and then fired, was developed in Egypt in the early Islamic period and became widespread in Spain. The most detailed description of glassmaking of this period was documented by Presbyter Theophilus around AD 1000. Theophilus wrote extensively on the making of glass in his time in his comprehensive technological manual entitled Diversarum Artium Schedula, which was first published by Leiste in 1781. According to Bontemps, who translated this treatise around 1843, Theophilus was a diligent German monk who, in his manuals, describes details of a set of state-of-the-art glass technologies or manufacturing processes. Bontemps’ translation has not only provided us with the technical manual but has also given us an insight into the cultural aspects of glassmaking during this period. Theophilus’ book, combined with a careful study of what is left of the great stained-glass windows in the European cathedrals, can help us in describing the state of the art of glass technology between the years 1100 and 1250 AD (Hawthorne and Smith 1979). Describing Theophilus’ work environment, George Bontemps wrote of the monk:

… after the matins and lauds and before going to his glassmaking workshop to produce, for the Glory of the Lord, for the wealth of the Monastery, for his Brothers in Christ and for the Holy Services, [he made] beautiful and delicate chalices with marvellous colours, often obtained by sheer chance, thanks to the alchemy and secret recipes of the ancient masters (Matteoli 1999).

In the fourth century, glass in architecture flourished in religious buildings in Rome. A good example is Constantine’s Church of St Paul, built in AD 337, where coloured glass was used. The combination of strong Mediterranean sun and the coloured glass prompted the creation of a wonderful display of biblical stories within the churches. The experience of moving from the opaque exteriors and sunny Mediterranean streets to dark interiors with such colourful and richly informative windows must have been quite an experience in the fourth century. At this time, fine glassworks were also founded further north in Cologne, Germany. It is believed that migrants from Venice and the eastern Mediterranean had established themselves in Cologne, where they continued their trade during this period. It was there in Germany that the word glesum, meaning ‘transparent’, was first used, from which the word ‘glass’ came. The following 200 years saw a decline in glassmaking north of the Alps, while traditional locations of the industry (such as Palestine and Syria) continued to flourish, producing more highly distinctive and elegant pieces such as the collared flasks and decorated lamps being manufactured in Fayoum, Egypt.

The political unrest in Europe during the tenth century prevented further development of glassmaking. Centres of glassworks in Byzantine Europe continued to exist in Belgorod (near Kiev) and Corinth, established by Greeks emigrating from Egypt. Spain was, however, an exception: glassworks flourished, since imports from the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt provided both style and knowledge of technology after the Muslim invasion in the eighth century. Soon, local glass-blowers established themselves in Andalusia. Although the glass industry was stagnant until the thirteenth century, architectural glass largely improved with the adoption of the industry by the monasteries. The cylinder method of making glass for windows was in operation in the main centres of production in Burgundy, Lorraine and the Rhineland, and exported to other European countries, in particular to England. The cylinder technique enabled the production of relatively large flat glass panes. Church buildings were the first to be glazed. The techniques for making stained-glass windows for cathedrals and churches were also well established in Europe by the twelfth century. Good examples of this period include Augsburg Cathedral in AD 1065 and St. Denis (Paris) in the twelfth century. Stained-glass windows were also used in churches in the Central Balkans: a good example is the window in the dome of the Church of the Blessed Virgin in Serbia (AD 1190). During the twelfth century, glass techniques continued to be developed in Aleppo and Armenaz (Syria), as well as Al Fustat (Egypt) under the Mamluk rule. Despite such flourishing in production and trade, the use of glass in architecture was limited to lamps and other interior items. Glass windows were rarely used. Lamps for mosques were particularly popular in both Syria and Egypt during the twelfth century (Figure 1.5). An early use of glass windows was reported in the Ahmed Bin Toloun mosque (AD 868) and in houses such as the Palace of Bash...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Glassworks: The History of Glass and its Architectural Identity

- 2 Green Glass: Environmental Perspectives on Using Glass in Architecture

- 3 Glazed Spaces: Constructing Place Identity

- 4 Shattered Glass: Structures of Power

- 5 Seeing Through Glass: A Technical Review

- 6 A Glazed Future: Rethinking Identity

- Bibliography

- Index