- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The twelve papers written for this volume reflect the wide scope of Annemarie Weyl Carr's interests and the equally wide impact of her work. The concepts linking the essays include the examination of form and meaning, the relationship between original and copy, and reception and cultural identity in medieval art and architecture. Carr's work focuses on the object but considers the audience, looks at the copy for retention or rejection of the original form and meaning, and always seeks to understand the relationship between intent and perception. She examines the elusive nature of 'center' and 'periphery', expanding and enriching the discourse of manuscript production, icons and their copies, and the dissemination of style and meaning. Her body of work is impressive in its chronological scope and geographical extent, as is her ability to tie together aspects of patronage, production and influence across the medieval Mediterranean. The volume opens with an overview of Carr's career at Southern Methodist University, by Bonnie Wheeler. Kathleen Maxwell, Justine Andrews and Pamela Patton contribute chapters in which they examine workshops, subgroups and influences in manuscript production and reception. Diliana Angelova, Lynn Jones and Ida Sinkevic offer explorations of intent and reception, focusing on imperial patronage, relics and reliquaries. Cypriot studies are represented by Michele Bacci and Maria Vassilaki, who examine aspects of form and style in architecture and icons. The final chapters, by Jaroslav Folda, Anthony Cutler, Rossitza Schroeder and Ann Driscoll, are linked by their focus on the nature of copies, and tease out the ways in which meaning is retained or altered, and the role that is played by intent and reception.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Byzantine Images and their Afterlives by Lynn Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of ArtPart I

Manuscripts: Workshops, Subgroups, and Influences

1

The Afterlife of Texts: Decorative Style Manuscripts and New Testament Textual Criticism

Kathleen Maxwell

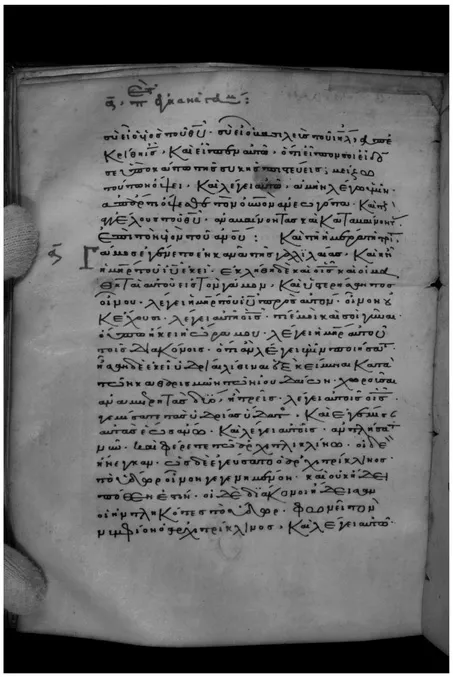

Byzantine manuscripts of the decorative style feature illuminations with large, powerfully silhouetted figures with pastel color schemes and flat architecture (Figure 1.1 = Plate 1). Their texts are characterized by a distinctive “low epsilon script” written in dark black ink with magenta titles (Figure 1.2).1 Decorative style manuscripts date from approximately 1150 to 1250 and comprise the single largest group of manuscripts in Byzantine art. While many are of mediocre quality, some decorative style manuscripts are truly extraordinary. In fact, they represent the only deluxe Greek manuscripts from the first half of the thirteenth century, as well as almost all that is known of Byzantine illuminated manuscripts of the late twelfth century.

Annemarie Weyl Carr published 109 manuscripts of the decorative style group in 1987, and it was she who proposed the title by which they are currently known.2 Carr organized the decorative style manuscripts into eight subgroups based on artistic, paleographical, and codicological similarities. She defined three initial, three central, and two late subgroups and was able to assign nearly 80 percent of the decorative style manuscripts to one of the subgroups based on these qualifications.

![Fig. 1.1 [Plate 1] Münster, Bibelmuseum der Universität Münster, cod. gr. 10, fol. 154v. Evangelist John the Theologian.](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1634970/images/fig00003-plgo-compressed.webp)

Fig. 1.1 [Plate 1] Münster, Bibelmuseum der Universität Münster, cod. gr. 10, fol. 154v. Evangelist John the Theologian.

Carr argues that most decorative style manuscripts probably originated in Cyprus and/or Palestine; but their origin has proven difficult to pinpoint, and some scholars believe that Nicaea or even Constantinople might be more plausible.3 The chronology of the decorative style manuscript group has also been challenged by the recent discovery of a new member of the group in Sofia, Bulgaria, that is dated to 1285.4

Fig. 1.2 Münster, Bibelmuseum der Universität Münster, cod. gr. 10, fol. 157v. Text page.

This study attempts to shed light on the origins of decorative style manuscripts by examining their Gospel texts in the context of the scholarship of New Testament textual criticism. I focus especially on the data published since 1998 by the Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung of Münster, Germany—henceforth, referred to as the Münster Institute.5 The data generated by the Münster Institute reveal surprising connections between the Gospel texts of various members of the decorative style subgroups, as well as between these manuscripts and others which are not associated with the decorative style. The New Testament text critics’ data underscore the remarkably complex relationships that must have existed between scribes and illuminators, and the books they copied and decorated.6

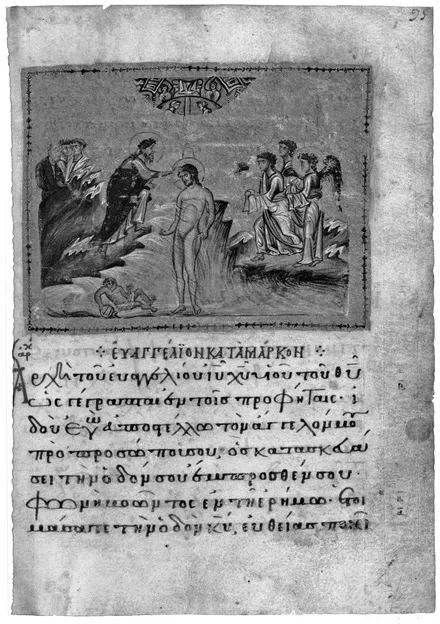

Fig. 1.3 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), cod. gr. 75, fol. 95r. Beginning of the Gospel of Mark.

In the following, I will concentrate on the textual data that support the following preliminary conclusions.7 First, for the manuscripts of the decorative style assigned by Carr to the initial subgroups, close artistic, paleographical, and codicological ties between manuscripts do not serve as an accurate gauge of textual relationships.8 My analysis of the Münster Institute’s data suggests that while members of a particular subgroup of the decorative style are usually textually related to at least one other member of their subgroup, they may be more closely related, in their texts, to members of other subgroups of the decorative style or even to unaffiliated Greek manuscripts of various dates.9 Second, at least ten decorative style manuscripts demonstrate compelling textual affinities with deluxe Constantinopolitan products such as Oxford, Bodleian Library, E.D. Clarke 10; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), cod. gr. 75 (Figure 1.3); and Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, Ms. 710/5.10 The latter two manuscripts are associated with one of the most famous Constantinopolitan illuminators of the twelfth century, the Kokkinobaphos Master.11 Third, while the figural style and ornament of decorative style manuscripts lost favor by the end of the thirteenth century, the data generated by the Münster Institute suggest that the Gospel texts of decorative style manuscripts continued to serve as exemplars for Byzantine scribes for at least two centuries after the demise of the decorative style itself.

A Note on Methodology

New Testament text critics study approximately 2,000 continuous text Greek manuscripts of the Gospels that survive from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries.12 These manuscripts’ texts are compared in order to recognize variant readings and, on the basis of these variants, to classify the manuscripts by subgroup. Textual variants are typically the result of changes that are introduced in the copying process, including differences in word order, substitutions made by scribes, and mistakes that result when a scribe skips from a similar phrase up or down to the next similar phrase on a page.13 Text critics distinguish between accepted variants (those that allow a manuscript to be categorized within a specific subgroup) and those that are more likely to be errors introduced by the current scribe responsible for copying the manuscript.14 Significant textual variants permit a manuscript to be classified within a specific subgroup.15 Complete collations of all witnesses of the Gospels are not feasible at the present time, so text scholars selectively examine (that is, collate) a Gospel’s text at specific predetermined points which they deem important.

In the following discussion, I will be referring to several different lists of data provided by the Münster Institute in their volumes on the four Gospels.16 The Group List displays those manuscripts that differ by more than 10 percent from the Majority Text.17 That is, it lists those Greek manuscripts that are closer to each other than they are to the Majority Text.18 In addition, the Group List includes those manuscripts that are closest to those that differ by more than 10 percent from the Majority Text. Thus, this list provides information about distinctive groupings among Greek Gospel manuscripts.19 The Majority Text is not a text per se, but rather is “a statistical construct that does not correspond exactly to any known manuscript. It is arrived at by comparing all known manuscripts with one another and deriving from them the readings that are more numerous than any others.”20

Decorative Style Manuscripts: The Subgroups

We return to the subgroups that Carr identified for the manuscripts of the decorative style21 (see Table 1.1). To her list of eight subgroups, I have added one more called “Unassigned Gospel Books.” This subgroup includes those Gospel books for which Carr did not have enough evidence to assign to one of her eight subgroups. Usually, these books are missing their illustrations and/or were only available to her in microfilm format. Thirteen Gospel books fall into this category.

The numbers in parentheses in Table 1.1 indicate the total number of manuscripts assigned to each subgroup by Carr, while the right-hand column ind...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Editor

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction: The Collegial Life of Annemarie Weyl Carr

- Part I Manuscripts: Workshops, Subgroups, And Influences

- Part II Intent and Reception

- Part III Cypriot Influences

- Part IV The Nature of Copies

- Publications of Annemarie Weyl Carr

- Index