- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding the Tea Party Movement

About this book

Hailing themselves as heirs to the American Revolution, the Tea Party movement staged tax day protests in over 750 US cities in April 2009, quickly establishing a large and volatile social movement. Tea Partiers protested at town hall meetings about health care across the country in August, leading to a large national demonstration in Washington on September 12, 2009. The movement spurred the formation (or redefinition) of several national organizations and many more local groups, and emerged as a strong force within the Republican Party. Self-described Tea Party candidates won victories in the November 2010 elections. Even as activists demonstrated their strength and entered government, the future of the movement's influence, and even its ultimate goals, are very much in doubt. In 2012, Barack Obama, the movement's prime target, decisively won re-election, Congressional Republicans were unable to govern, and the Republican Party publicly wrestled with how to manage the insurgency within. Although there is a long history of conservative movements in America, the library of social movement studies leans heavily to the left. The Tea Party movement, its sudden emergence and its uncertain fate, provides a challenge to mainstream American politics. It also challenges scholars of social movements to reconcile this new movement with existing knowledge about social movements in America. Understanding the Tea Party Movement addresses these challenges by explaining why and how the movement emerged when it did, how it relates to earlier eruptions of conservative populism, and by raising critical questions about the movement's ultimate fate.

Information

Explaining the Timing and Pace of the Mobilization: Politics and Resources

Chapter 1

What’s New about the Tea Party Movement?

Beginning in the 1960s, a wave of social movement activism contributed to fundamental change in the United States. African Americans organized to dismantle Jim Crow segregation in the South and to secure voting rights and basic civil rights throughout the nation. Latinos and American Indians, inspired by the example set by the civil rights movement, also took to the streets. Feminists and gay rights activists organized to advocate progressive legislation, but also to change deeply rooted cultural norms that devalue women, gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgendered individuals. Young Americans led a movement against war in Vietnam, and others organized to reverse environmental degradation. While elected officials gave disproportionate representation to the wealthy and powerful, ordinary Americans acted outside institutionalized politics to pressure those officials to respond to calls for progressive change.

Protest of the 1960s also led to a fundamental change in the way that social scientists understood social movement activism. Previously, political protest was viewed as being more similar to crime and deviant behavior than it was to voting, lobbying, or other forms of political action. To a great extent, the fear of the masses reflected in the French social psychologist Gustave LeBon’s work remained influential. Writing at the end of the nineteenth century, LeBon described protest participants in the following manner:

by the mere fact that he forms part of an organized crowd, a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilization. Isolated, he may be a cultivated individual; in a crowd, he is a barbarian—that is, a creature acting by instinct. He possesses the spontaneity, the violence, the ferocity, and also the enthusiasm and heroism of primitive beings, whom he further tends to resemble by the facility with which he allows himself to be impressed by words and images—which would be entirely without action on each of the isolated individuals composing the crowd—and to be induced to commit acts contrary to his most obvious interests and his best-known habits. An individual in a crowd is a grain of sand amid other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will. (1952: 32–3)

While lacking much of the alarmist tendencies of LeBon, dominant theoretical perspectives of the 1950s and 1960s also treated protest as more of a psychological than a political phenomenon. Mass society theory (Kornhauser 1959) and collective behavior theory (Smelser 1962) proposed that changes in the structure of society generate discontent among subsets of the population, freeing those individuals from constraining social bonds. Protest was viewed as a response to anxiety, frustration, and a general sense of anomie.

These scholarly accounts of social protest were turned upside down in the wake of 1960s activism. Many graduates of social science PhD programs in the 1960s and 1970s were schooled in the streets as well as in the classroom. Their own activism on behalf of progressive causes carried over into their emerging scholarship (see Gamson 2011). Not surprisingly, these activist/scholars quickly revealed the extent to which earlier depictions of social movement participants lacked an empirical foundation. Indeed, subsequent research has consistently shown that movement participants tend to be embedded in dense social networks and they participate not to release psychic tension, but to bring about political and cultural change. Rather than focusing on how structural changes can generate anomie and discontent, social movement scholars instead gave attention to how movement activists strategically capitalize on the availability of organizational resources (McCarthy and Zald 1973, Oberschall 1973, Gamson 1975, Morris 1984), exploit favorable shifts in the political environment (Tilly 1978, McAdam 1982, Tarrow 1994), and construct interpretive frames that entice individuals to participate in collective action (Snow et al. 1986).

Progressive social movements have continued to press demands for a more responsive government, and resource mobilization theory, political opportunity theory, and framing theory continue to be useful for analyzing and explaining these movement dynamics. Yet since 2009, one of the social movements that has received the most public attention and has had, arguably, the most influence on American politics, draws support primarily from white middle-class Americans (Zernike 2010). Its members claim to be acting in the spirit of the nation’s founding fathers, while they seek to limit the government’s role in providing for the welfare of the nation’s citizens. Through top-down as well as bottom-up organizing, and with the benefit of free publicity generated by extensive media coverage, the Tea Party movement can boast of millions of members and adherents. A New York Times/CBS News poll conducted in April 2010 showed that 18 percent of respondents identified themselves as Tea Party supporters (see Zernike 2010). Because Tea Party supporters are primarily drawn from Republican voters, Republicans running for public office have come to understand that their political fortunes depend heavily on how they are viewed by Tea Party supporters.

How did the Tea Party gain so many supporters and so much influence? Although a wave of research on the movement is currently underway, as of this writing very little social scientific research has been published on the topic. Much in the same way that research on social movements of the 1960s led to fundamental change in social movement theory, research on the Tea Party could open up new lines of inquiry and generate new insight into social movement dynamics. The emergence of conservative movements such as the Tea Party, as I discuss below, cannot be explained with theories that were developed with progressive movements in mind. The Tea Party, therefore, will require us to develop new tools designed to account for the emergence of conservative collective action. In this chapter, I offer some guidance on how we can most effectively theorize and study Tea Party activism. I begin by discussing the limitations of extant theory. Following that, I compare the Tea Party to another middle-class mass movement in American history—the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s—and I discuss how the power devaluation model, a theory that I previously developed to account for the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, could be used to study both the emergence and the trajectory of the Tea Party movement.

Grievances Do Matter (for Conservative Movements)

While terms such as “progressive” and “conservative” can be defined in many different ways, here I offer operational definitions that draw attention to a fundamental difference between the two types of movements, with these differences being particularly relevant for explaining their emergence and growth. I see progressive movements as those that are primarily oriented toward winning new rights and privileges for constituents—rights and privileges that are available to other groups in society but have been denied to the movement’s constituents. Conservative movements, on the other hand, are oriented primarily toward preserving, restoring, or expanding constituents’ pre-existing privileges. This process typically involves protecting traditional economic and social arrangements that offer advantages to constituents—advantages that come at the expense of other groups in society. Conservative collective action is typically instigated by beneficiaries of inequality who are resisting efforts to redistribute wealth and resources or who are resisting other changes that might undermine benefits they receive due to preferential treatment that is given to their own social group.

This fundamental distinction between progressive and conservative movements is critical when it comes to explaining movement origins. As resource mobilization theorists pointed out long ago, many disadvantaged and relatively powerless groups are oppressed and downtrodden for decades, and even centuries, before collective action emerges (McCarthy and Zald 1973, Oberschall 1973, Jenkins and Perrow 1977). Or, in many cases, collective action fails to emerge at all. The presence of grievances and the intensification of grievances are poor predictors of the emergence of collective action among the oppressed (McAdam 1982). Failure to act, in such cases, typically has more to do with the lack of an organizational infrastructure or a political climate that is so oppressive that group members perceive that organizing to bring about change would be futile (Tilly 1978, McAdam 1982, Tarrow 1994). In these cases, social movement researchers have rightly focused on time-variant factors such as the availability of organizational resources and openings in the political opportunity structure that make it possible to act to address longstanding grievances.

This logic, while perfectly sound when applied to progressive movements, does not apply when the goal is to explain the emergence of conservative collective action. Constituents of the Tea Party, for example, are not oppressed and downtrodden. Supporters have ready access to organizational resources, they need not fear political repression when they stage a protest event, and they need not look far to locate influential political allies. Any attempt to explain the emergence of the Tea Party in terms of resources and political opportunities, therefore, begs the question why the movement emerged in 2009 rather than at some other historical moment when resources and political opportunities were just as abundant and accessible. Resources and political opportunities may still be essential for mobilization, but they do not explain the timing of movement emergence. Explanatory power, when studying movements that act on behalf of relatively privileged actors, comes from identifying what has changed over time that provided the impetus to draw upon pre-existing organizational resources and to exploit pre-existing openings in the structure of political opportunity. What new grievances provided the incentive to act?

What about “Threat”?

The Tea Party is just one of many conservative movements that have been active throughout US history, but the vast majority of scholarly attention has been directed toward progressive movements. Conservative movements, however, have not been completely ignored in the academic literature. In some studies, researchers fall back on assumptions about protest participants that were broadly held prior to the 1960s, proposing that conservative movements have more to do with psychological states such as status anxiety and frustration than with political action designed to protect collective privileges (Lipset and Raab 1970, Wood and Hughes 1984, Burris 2001). Yet much recent research suggests that conservative activists, like progressive activists, tend to be embedded in dense social networks (Blee 1991, 2002, MacLean 1994, McVeigh and Sikkink 2001). Little evidence, also, has been provided that indicates that conservative activists are any less rational than progressive activists.

Avoiding irrationalist assumptions about the characteristics of protest participants, some researchers have shown that collective action can result from suddenly imposed grievances (Walsh 1981) or from a disruption in the quotidian (Snow et al. 1998). While reactions to suddenly imposed grievances need not be conservative in nature, these arguments can be applied to conservative movements because members of a particular social group may act in response to sudden changes that are detrimental to their interests. Along these same lines, researchers are increasingly giving attention to how collective action can emerge as a reaction to some form of threat. According to this line of thinking, individuals may act collectively against a real or perceived threat when they conclude that the costs of inaction—or the losses that would result from letting the threat go unanswered—exceed the costs of taking action (Tilly 1978, Goldstone and Tilly 2001, Van Dyke and Soule 2002, Almeida 2003). This general approach is very similar to one that has been applied in studies of racial and ethnic conflict for several decades. In this research, ethnic conflict is shown to be most likely to occur when previously subordinated groups become increasingly capable of competing with majority group members for scarce and valued resources (Blalock 1967, Bonacich 1972, Nielsen 1985, Olzak 1992). Under these circumstances, members of the majority group may initiate collective violence in an effort to drive away or intimidate potential competitors.

Threat is a useful concept in social movement research because it appropriately focuses attention on time-variant grievances that can provide incentives to act collectively for segments of the population that are not held back by a lack of organizational resources or by a closed political opportunity structure. Yet we might think of threat as more of a starting point, rather than a final answer, when it comes to understanding conservative social movements. While conservative action may be understood as a reaction to a threat to collective interests of relatively privileged actors, there remains much to learn about the nature of the threat. We should take care not to neglect the causal complexity of movement emergence, and we should avoid post hoc evaluations that stretch the definition of the “threat” concept so far that it loses explanatory power. Close attention, also, should be given to the context in which collective action emerges. Conditions that pose a threat to constituents of one conservative movement may be irrelevant to other conservative movements. We must also recognize that a threat to collective interests does not always lead to collective action. The link between threat and action, therefore, must be theorized and researched empirically. The power devaluation model, which I describe in the next section, offers precise guidance on where we should look when seeking to explain conservative collective action, but it is also a model that can be easily adapted to different historical and cultural contexts.

The Power Devaluation Model

The power devaluation model is built upon an assumption that individuals are most likely to act in defense of their interests through social movement activism when their power to defend their interests through institutionalized channels is in decline. Individuals may face threats to their interests on a regular basis, but as long as they maintain the capacity to control outcomes and deflect challenges, there will be little incentive to participate in social movement activism. Therefore, a focus on power seems to give us the most purchase when studying conservative movements. Under ordinary circumstances, members of relatively privileged groups seek to protect their interests through institutionalized arrangements that systematically protect their advantaged position, while simultaneously making their advantages appear to be fair, legitimate, and natural (Gaventa 1982, Jackman 1994). Incentives to engage in activism arise when institutionalized power is increasingly ineffective.

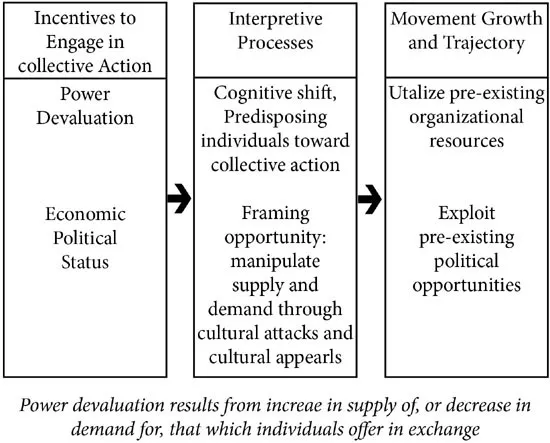

As depicted in the simple model in Figure 1.1, the power devaluation model focuses on three key aspects of conservative mobilization: 1) incentives to act, 2) interpretive processes, and 3) movement growth and trajectory. I consider three sources of power devaluation that can potentially generate incentives to engage in conservative activism. These include power rooted in economic exchange, political exchange, and status-based exchange. Conceiving of power as being rooted in exchange (e.g., Simmel 1950, Emerson 1962, Blau 1964) has some distinct advantages when studying conservative movements. As Tilly (1998) notes, durable inequality is reproduced through both “opportunity hoarding” and “exploitation.” In some cases, relatively privileged actors secure their advantages by restricting competition (opportunity hoarding). Yet in other instances, privileged actors secure advantages by extracting valued resources from members of other groups (exploitation). It is necessary, then, to consider that for some, conservative collective action may be a response to competitive pressure, but in other instances it may be in response to factors that interfere with processes of exploitation. Tolnay and Beck (1995), for example, call attention to how elite and non-elite white southerners had different motivations for lynching African Americans in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Some white elites saw lynching as useful for maintaining control over labor, while non-elite whites were motivated by a desire to eliminate or drive away competitors. The nature of the threat to white interests, in this case, was very different depending on white southerners’ positions within exchange relationships.

Figure 1.1 Power devaluation dynamics

I offer a precise way of conceptualizing “power devaluation” so as to avoid post hoc explanations of outcomes of interest that stretch the concept too broadly. We can think of one’s “purchasing power” within an exchange market as being determined by supply and demand. Power devaluation results from either increase in supply of those offering the same commodity in exchange or or from a decrease in demand for that which is offered in exchange. Common mediums of exchange within an economic market include labor, wages, goods, services, and money. In a political market, they include votes, money, representation, and patronage. In a status-based market, certain traits and behaviors are exchanged for esteem (Emerson 1962, Blau 1964). We should expect to find that core constituents of a conservative movement are experiencing power devaluation in at least one exchange market (economic, political, or status). Incentives to act would be especially strong if individuals are experiencing devaluation in more than one market. For example, if someone experiences economic devaluation but retains power within political exchange, she might use political power in an effort to restore economic power. Similarly, economic power can be used to restore power devaluation in political or status-based exchange. Simultaneous devaluation in multiple markets, however, provides an incentive to act outside of traditional institutions through social movement activism because institutional action is increasingly ineffective.

Power Devaluation and Interpretive Processes

Decades of research on social movement framing processes has taught us that we should not expect a direct and immediate link between power devaluation and participation in collective action (McAdam 1982, Snow et al. 1986). Individuals act based upon their perceptions of reality, rather than in response to objective conditions. The power devaluation model stipulates that objective power devaluation (as described above) can produce a shift in the way in which those affected understand their own circumstances and also...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Table

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Explaining the Timing and Pace of the Mobilization: Politics and Resources

- Part II Who Mobilized and Why? Ideology, Identity, and Emotions in the Tea Party

- Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding the Tea Party Movement by Nella Van Dyke, David S. Meyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Ideologies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.