![]()

1 The European Union as a dualist political economy

Understanding core–periphery relations

José M. Magone, Brigid Laffan and Christian Schweiger

Conceptualising core–periphery relations in the European Union

The rapid expansion of the EC/EU since 1973 has created a more heterogeneous and diverse supranational organisation in ways that are negatively affecting its multilevel governance capability (Magone, 2008). This is a major worry among policy-makers and high-ranking officials in Brussels (Maystadt, 2011; Piris, 2012).

The main argument of this volume is that the process of enlargement has created a core–periphery cleavage or divide in the European Union that has considerable implications for perceptions of power relations, influence and leverage among member states. The European Union is not a homogenous economy, but rather a dualist one. It consists of a core economic Europe and a peripheral one – or, as argued by Bela Galgóczi in this volume, several peripheries. A conflict among various perceptions of the European Union has led to tensions between core and periphery countries in the Eurozone with repercussions for the European Union as a whole.

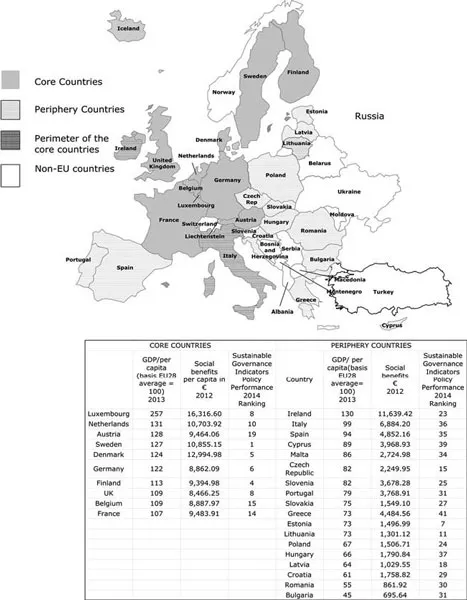

Conceptually, we identify as ‘core’ the highly developed economies of western and northern Europe (Germany, France, the UK, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg) and as ‘periphery’ the less developed economies of the European south (Portugal, Spain, Greece, Malta and Cyprus), centre (Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia and Poland), east (Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia) and the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania). However, there are three cases that fall on the perimeter between the core and the periphery: France due to its stagnating economy, Italy due to the dualism of north and south, and Ireland due to its dynamism and strong investment in research and development (see Figure 1.1).

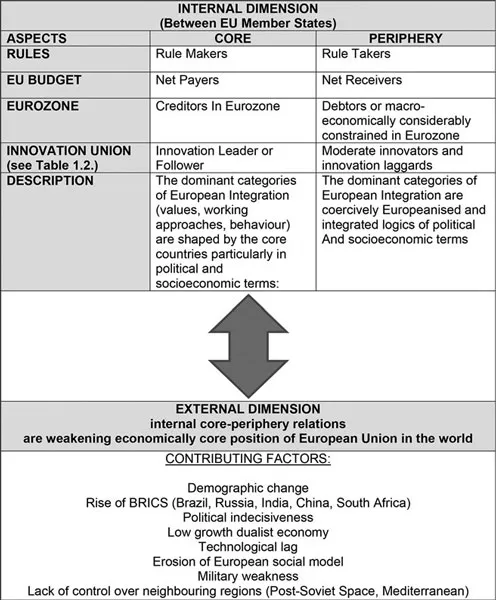

Our focus will be mainly on the internal dimension of the European political economy using theoretical, comparative and case studies. This centrality of the internal dynamics of the European political economy is analysed through the lens of core–periphery relations (see Figure 1.2).

Nevertheless, internal and external dimensions of the present and future prospects of the European political economy are intertwined and influence each other. Without an internally integrated, competitive, ‘even’ economy it will be quite difficult for the European Union to project its European social market economy model onto the world economy. In the context of the declining power of global Europe, our volume is a major original contribution to study of the changing internal politics of the European Union.

Figure 1.1 Map of core–periphery Europe

Note: Ireland and Italy are on perimeter of the core but simplification aligns them at the periphery in the figure.

Source: Eurostat and Bertelsmann Foundation Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI).

Figure 1.2 Conceptualising core–periphery relations in the European Union

This chapter sets out the context for the study of core–periphery relations in the European Union’s dualist economy. Following this introduction, the chapter is divided into five further sections. In the next section we expand our conceptualisation of core–periphery relations. This is followed by a section on the emergence of the Troika as a power instrument of asymmetrical relations between core and periphery countries. The third section briefly discusses the implications of this divide or cleavage for the position of the European Union in world politics and the global economy. The penultimate section reviews the chapters in the volume, and finally some conclusions are drawn.

Recognising the European Union’s dualist economy

The recognition of the socio-economic heterogeneity of the European Union is not a new idea (Höpner, Schäfer, 2008, 2015). In this book, we go beyond the mere recognition of the socio-economic heterogeneity in the European Union by reconceptualising it as a core–periphery cleavage with profound implications for the political and economic relations between member states.

Although studies of core–periphery relations have always been a part of European integration studies (e.g. Leonardi, 1993; Bachtler et al., 2014), the usual perspective has focused on convergence rather than divergence as a cleavage or divide. Moreover, the tendency has been to examine core–periphery relations within member states, not in the European Union as a whole (see Wright, Mény 1985; Jones, Keating, 1995; Le Galés, Lequesne, 1998). Studies applying a more pan-European approach to core–periphery relations have thus far been quite rare (see Cole, Cole, 1997; Hudson, Williams, 1999; Magone, 2006: 192–199).

Most of the gains in GDP convergence have been lost over the past few years due to the financial crisis. Portugal, Spain, Greece, Italy and Ireland all had to deal with decreases in their GDPs, and all have experienced high levels of unemployment. Between 2008 and 2013, GDP in Greece declined by 26.2 per cent, compared to 8.9 per cent in Italy, 7.6 per cent in Ireland, 6.9 per cent in Portugal and 5.8 per cent in Spain (Eurostat, 2014a).

National selfishness was quite prominent during the Eurocrisis, demonstrating that solidarity between member states still cannot be taken for granted (see the chapter by Stefan Auer). This indicates that the European Union is presently in a process of transition from methodological nationalism to methodological Europeanism. The recent re-emergence of methodological nationalism in dealing with the Eurozone’s problems is a clear sign that such a transition is underway. ‘More Europe’ would have been a better and cheaper way to solve the Eurocrisis; instead, intergovernmental solutions like the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) were developed. As Helen Callaghan asserts, the European integration process has been eroding national versions of capitalism, replacing them with a hybridisation in the context of European multilevel governance. This hybridisation signifies a move towards a liberal market economy. Notably, it is becoming more difficult for socially homogenous blocs to control this changing reality (Callaghan, 2010: 578–595).

The social sciences in particular are still predominantly framed in a national perspective, not a European one. According to Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glicker Schiller, the methodological nationalism assumption is ‘the assumption that the nation/state/society is the natural social and political form of the modern world’ (2002: 302). The authors show that the framing of the world since the second half of the nineteenth century has been shaped by social sciences based on the perspective of different nation-states. As Antoine Vauchez argues, methodological Europeanism is part of a reframing process acting through the acquis and equipment of the European Union that can only represent a long-term transition to a new European frame of mind. The move towards methodological Europeanism is thus dependent on what the European Union wants to be in the future (Vauchez, 2015). Either it wants to keep the status quo by muddling through or rather become a superpower shaping the categories of power in the world towards a more social and environmentally friendly capitalism.

Although always existent in the background, core–periphery relations were brought to the fore by the Euro- and sovereign debt crises. The debate over this divide then became a ‘domestic’ European discussion that was predominantly conducted within the Eurozone. Rosenau characterises the growing interdependence of analytically diverse domestic and international fields of action as ‘intermestic’ (Rosenau, 1990, 2000). We can identify a similar process of interdependence between the supranational and national levels in the European Union, which (paraphrasing Rosenau) may be characterised as ‘Euromestic’, a term coined by Janerik Gidlund (2000: 254).

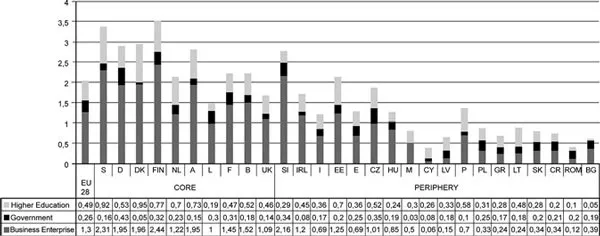

This is not the place to present all of the indicators that map this socio-economic core–periphery divide (see Magone, 2011, 2013). Most of the chapters in this volume will address this aspect in greater detail. Here, it suffices to illustrate the lag in terms of research and development between the core (advanced) and the peripheral (less developed) economies (Eurostat, 2014b). Figure 1.3 clearly shows a considerable gap between core and periphery, although there are some outliers (such as Slovenia and Estonia).

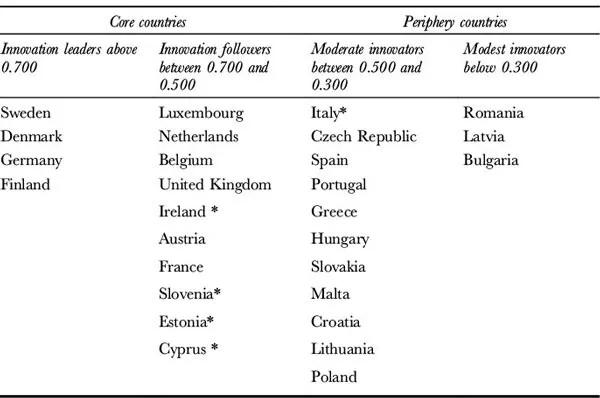

The innovation union recently established in the context of the Europe 2020 strategy merely confirms this divide. The so-called ‘innovation score board’ for 2014 still depicts a variety of research cultures among the member states, reconfirming the socio-economic core–periphery cleavage (European Commission 2010a, b; European Commission, 2014) (see Table 1.1).

Figure 1.3 Research and development expenditure in the European Union, 2012

Source: Eurostat, 2014b.

Table 1.1 EU member states’ innovation performance index, 2014

This selection of indicators makes a case for the dualist nature of the European economy. In socio-economic terms, one can also refer to other indicators (productivity per working hour, quality of the welfare state, nature of flexicurity, job quality, industrial relations, gender and social equality) that further corroborate the core–periphery divide. In many ways, one could characterise the cleavage or divide in terms of core efficient national governance and peripheral less efficient one. In some cases, this lack of efficiency degenerated to ‘bad’ governance like in the case of Greece (see Figure 1.1.)

In sum, the dualist economy of the European Union is an important factor that should be considered when analysing further European integration. This dualism can be observed not only in socio-economic indicators but also in ‘Euromestic’ politics.

The end of the benevolent European Union: the invention of the Troika

Conflicts over the EU budget have erupted regularly over the past fifteen years, especially since the Berlin European Council of 1999. The European Union neglected to provide adequate resources for the mega-enlargement of the EU after 2004. The EU budgets for the periods 2000–2006, 2007–2013 and now 2014–2020 have not included any increase in resources; recently, there has even been a reduction of the budget to about €960 billion for a six-year period. At least seven countries have organised themselves in an attempt to prevent any increase in the budget: the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Finland, Sweden, Austria and the Netherlands, a group that has been labelled the ‘friends of better spending’. At the same time, a group called the ‘friends of cohesion’ (comprising the southern, central and eastern European countries as well as Ireland and Belgium) formed a lobby to keep structural policy funds at the highest level possible (EUInside 2012; Euractiv, 2014a; Euractiv 2014b; Magone 2014: 41–46).

For the southern, central and eastern European peripheries, the European Union is often regarded as a means to achieve more democratic accountability and transparency within their own countries. The perception of the European Union as a vincolo esterno (‘external link’) has been accompanied by idealised benevolent associations (Italian term taken from Dyson, Featherstone, 1996). However, this was the first crisis in which the Eurozone was affected. In this context, the Greek crisis was intrinsically linked to the survival of the euro as a currency. Consequently, the perceived ‘benevolent’ approach towards periphery economies changed overnight to one of strict conditionality, the main strategy employed to convince the markets that the Eurozone would be able to sort out its problems. This change in approach felt sudden for the southern periphery but had already been internalised in most central and eastern European countries, which had experienced a tougher, conditionality-driven European Union during their process of European integration. For these countries, the EU had introduced annual screening and progress reports to assess whether the required reforms – so-called ‘anticipatory Europeanisation’ – were being successfully implemented. In the process, the central and eastern European countries and the Mediterranean islands had to incorporate 80,000 pages of acquis communautaire into their national laws (Magone, 2008; see Auer on solidarity in this volume).

Resolving the unprecedented Greek situation before it led to the contagion of other weak Eurozone economies was a matter of urgency. In this period of uncertainty, the Franco-German alliance between the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the French President Nicolás Sarkozy led to the establishment of new principles based on austerity. This duo became known as ‘Merkozy’ due to the public consensus between the two leaders (Hinz, 2013; Schwarzer, 2013). Previously, President Sarkozy and Chancellor Merkel had had considerable disagreements on the nature and the scale of the EU’s collective response to the crisis. After several meetings, the two leaders were eventually able to achieve a compromise acceptable to their different views on the crisis (Crespy and Schmidt, 2014).

The Troika emerges as the symbol of the conditionality-driven policy of ‘coercive Europeanisation’ employed when everything else fails (term taken from Angelos Sepos in chapter 3 in this volume).

Klaus Armingeon and Lucio Baccaro argue that Ireland and countries in southern Europe are being forced to follow the German model of internal devaluation, which is clearly intended to keep inflation low. Price and wage stability are essential elements of this policy. However, without the economic development level of Germany and without a generous welfare state, such policies are quite costly and dangerous, potentially leading to a cycle of permanent austerity and pauperisation (Armingeon, Baccaro, 2012: 261–269; on the ‘German stability culture’ see Howarth, Rommerskirchen, 2013).

At first against it, Chancellor Angela Merkel and her finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble changed their minds when the Troika was endowed with strong monitoring powers. Schäuble wanted most of all to make sure that conditions for fiscal consolidation in the crisis countries would not be determined by the IMF alone.This point was also supported by the Netherlands (see also Hinz, 2013; Schwarzer, 2013; for a constructive discourse approach, see Crespy, Schmidt, 2014). The IMF was the model to be followed, a...