- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Farmer in England, 1650-1980

About this book

Farmers held a pivotal role in the capitalist agriculture that emerged in England in the eighteenth century, yet they have attracted little attention from rural historians. Farmers made agriculture happen. They brought together the capital and the technical and management skills which allowed food to be produced. It was they - and not landowners - who employed and supervised labour. They accepted the risk inherent in agriculture, paying largely fixed rents out of fluctuating and uncertain incomes. They are the rural equivalent of the small businessman with his own firm, employing people and producing for markets, sometimes distant ones. Our ignorance of the farmer might be justified by the claim that they are ill-documented, but in fact farmers were normally literate and kept records - day books, journals, accounts. This volume goes some way to counter the claim that a history of the farmer cannot be written by showing the range of materials available and the diversity of approaches which can be employed to study the activities and actions of individual farmers from the sixteenth century onwards. Farm records offer invaluable insights into the farming economy which are available nowhere else. In this volume accounts are used in a variety of ways - as the means to access single farms, but also in gross, as a national sample of accounts, to reveal regional variation over time. For the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries the range of sources available increases enormously and farmers - indeed farmer's wives too - emerge as articulate commentators on their own position, using correspondence to outline their difficulties in the First World War. Some even developed second careers as newspaper columnists and journalists. This book focuses attention back on the farmer and, it is hoped, will help to restore farmers to their rightful position in history as rural entrepreneurs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Farmer in England, 1650-1980 by Richard W. Hoyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Recovering the Farmer

As is the case in every occupation in which a large number of persons are engaged, we find amongst farmers great diversity of character, means and attainments. The farming class includes men of every imaginable description and reputation, from the most honourable and upright down to those who would not hesitate to take every kind of advantage of their neighbours when they could find a safe opportunity of doing so. In it we find also men possessed of very considerable wealth – more than equal, in this respect, to meet any demands likely to be made on them in their circumstances; while we find also men of more moderate means, able only to carry on their businesses profitably, and also men who are much straitened in their circumstances as to be in a state of comparative poverty. In it we also find men possessed of strong natural talents, and of high attainments, fully qualified to carry on their business on enlightened principles; while of course, a large proportion are men of moderate capacity and attainments, sufficient to enable them to conduct their business in the usual routine way; and not an inconsiderable proportion are so ill-informed and unskilful as not to be able to conduct their concerns in such a way as to insure either profit or comfort to themselves, or those with whom they have to deal.

This great variety of character is only what is to be expected in a class of men made up of all grades of society; for here we find retired merchants and tradesmen, with professional men of every description, besides those that have been brought up as cultivators of the soil; and hence we find all kinds of management on different subjects held, according to the views entertained by the respective parties, which are, of course, biased according to the particular training each has had in his earlier pursuits and habits in life.2

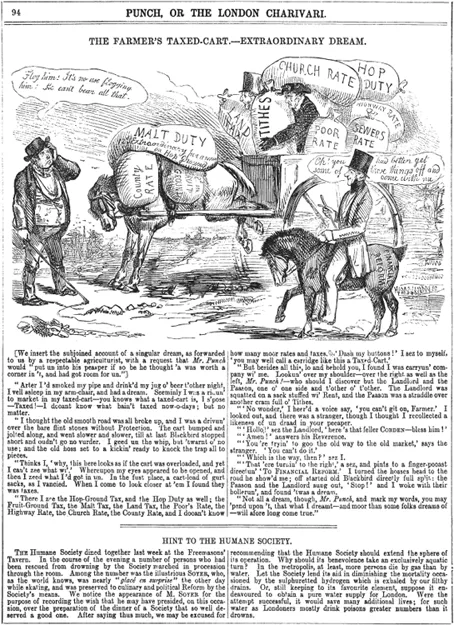

In writings on agricultural history, farmers are so often the bridesmaid and so rarely the bride.3 Their role in the capitalist agriculture that emerged in England in the eighteenth-century (and perhaps earlier) is well understood. Sometimes they owned the land they farmed, but more usually they rented it from a landlord who used the farmer to distance himself from the day-to-day business of cultivation. The farmer paid a rent – normally fixed for a period of years – and brought his capital and skill to exploit the land. He accepted the risk of farming, both in the sense of variable prices and variable yields. His income could therefore fluctuate widely from year to year, but out of this he had to pay rent, a variety of local rates and his workforce (Figure 1.1).4

To a limited degree the tenant farmer could use his landlord as a banker, looking to him for credit in poor years (by deferring rent payments) and perhaps asking him for investment in his farm. But without a farmer, the landlord had no rent, forcing him to either farm the land himself or leave it unexploited. Landlords needed tenants much more than tenants needed landlords: the relationship is, to coin a phrase, asymmetrical. Moreover, with the growing sophistication of farming, the landlord was not simply looking for a tenant with skill, but one with capital on a scale which would allow the farmer to operate the farm at a high level of efficiency to generate a high level of rent, and which would allow him to outride poor years.5 And in this English farmers, it would be agreed, were spectacularly successful. At its best English agriculture was extremely efficient. The size of the unit of production progressively grew through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries whilst the tendency of the farmer to become a tenant became more marked. Farmers themselves could live well, at least until the 1870s. Thereafter, farming profits were low, agriculture was depressed and farmers struggled to turn a penny in profit. This long agricultural recession lasted from the 1870s to the outbreak of the Second World War with only a few years of remission: something like it blanketed British farming between the late 1980s and the early years of this century. For a historically short period, from the beginning of the Second World War to the late 1980s, farming was again profitable, and farmers grew profits on a regime of state-fixed prices and government subsidies. By this time a much larger proportion of farmers were not tenants but owner-occupiers.

This is what the textbooks tell us. And yet we know very little about farmers as either a social group or as individuals, and one of the purposes of this introduction is to ask why. It is true that the seventh volume of the Agrarian History of England and Wales, edited by Ted Collins and covering the years 1850 to 1914, contains a chapter on the farmer by the late Gordon Mingay alongside ones on landlords and farm labour, and a further discussion by Alun Howkins, but none of the other volumes of the Agrarian History covering the last half millennium had one, certainly not the volume for the early twentieth century solely authored by Edith Whetham.6 Indeed, there is still no twentieth-century equivalent to Mingay’s chapter anywhere in the literature.7 Howkins’ recent textbook on the Death of Rural England paid the farmer little attention, lumping landowners and farmers together in one chapter and devoting the next one to farm workers and domestic servants.8 And so whilst books on landowners – collectively and singly – proliferate, farmers have yet to find their Boswell – or their F.M.L. Thompson.9

Figure 1.1 ‘The Farmer’s Taxed-Cart’, from Punch, 9 March 1850, p. 94

The purpose of this book is to focus attention on the farmer. We do not propose a revival of the old approach of eulogising a minority of improving farmers or men of unusual prominence.10 Instead our farmers are selected for the quality of the records they left behind, so whilst their lives and contribution to progress might be more ordinary, the historian is able to draw their economic and even political life in greater detail. But our hope is, that like the progressive farmer, we will be emulated. We hope to show the potential yields that might be secured by exploiting the farmers’ own records and other sources which record their voices.

I

Before proceeding further, we ought to note that the title of this book is, to a degree, an anachronism.11 Whilst today we understand a farmer to be a person who cultivates land for profit rather than subsistence (so ‘farmer’ is the opposite to ‘peasant’), the usage was less well established in the eighteenth and earlier centuries. The word is a coinage from the verb ‘to farm’, whose original meaning was to take an asset at rent. It was therefore usual to talk of the farm of lands but also the farm of taxes or the farm of tithes. Early usages of this sort are noted in the Oxford English Dictionary from Chaucer onwards. We have William Harrison in the 1560s speaking of ‘The yeomen are for the most part farmers to gentlemen’ meaning that they were tenants. It was a small step sideways from the farming of any asset to the more specific meaning of ‘One who rents land for the purpose of cultivation’. The current definition of farmer as one who ‘One who cultivates a farm, whether as tenant or owner; one who “farms” land, or makes agriculture his occupation’ is familiar from the late sixteenth century onwards. On the other hand, the people we call farmers were widely referred to as yeomen or husbandmen, both coinages surviving into the nineteenth century. It may be suggested that yeoman was a status designation where farmer was more of an economic designation, and people who were farmers preferred to be called yeoman (or husbandman) on formal occasions. Yeomen may have been regarded as farmers who owned their own land albeit, in some cases, as a copyholder rather than a freeholder. The Oxford English Dictionary helpfully quotes William Cobbett on this point in 1821: ‘Those only who rent ... are, properly speaking, farmers. Those who till their own land are yeomen; and, when I was a boy, it was the common practice to call the former farmers and the latter yeomen-farmers.’ Of course this may have been a pedantic distinction: someone meeting a cultivator of the land in the road could hardly ask about his tenurial status before deciding whether he was a farmer or a yeoman. Increasingly it was simply assumed – from manners and dress – that he was a farmer. Of course, well-off farmers might well expect to be called gentlemen and, of course, plenty of gentlemen farmed.

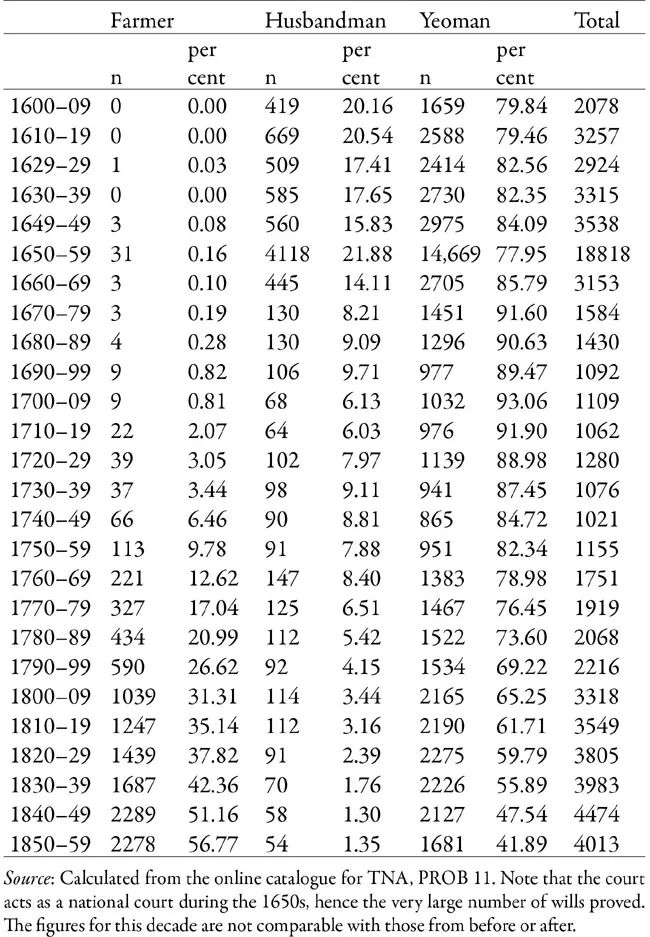

Table 1.1 Farming occupations in wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1600–1858

The way in which the three titles of farmer, husbandman and yeomen continued to be used side by side (and perhaps interchangeably) may be seen from Table 1.1. This gives the relative usage of the terms by persons making wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury between 1600 and the closure of the court in 1858. The numbers are large, but this is an odd sample because those whose executors sought probate here, rather than at a diocesan court, were probably more prosperous individuals drawn mainly from southern England. In the 1650s the nature of the court changed and it was, for a short period, the national probate court, hence the large number of wills proved in that one decade. The word ‘farmer’ as an occupational designation was virtually unknown before the Civil War and really only entered common usage after the beginning of the nineteenth century. Husbandman as a descriptor tailed away after the mid seventeenth century but the title was still being used in the early nineteenth by small numbers of testators whilst – surprising to say – there were nearly as many people coming to the court each year in the early nineteenth century being called yeomen as there were before the Civil War. Contemporary usage therefore differs somewhat from the historians’, for many of the latter would probably regard the title yeoman as obsolete by the beginning of the eighteenth century, and would see its reappearance late in the century as the name for the militia as being a deliberately anachronistic revival, which conveyed a sense of solidity and patriotic virtue.

There would doubtless always have been a high degree of interchangeability. In 1651 Nathaniel Newbury published The Yeoman’s Prerogative or the Honour of Husbandry: A Sermon Preached to Some and Dedicated to all the Yeomen and Farmers of Kent but if he meant to imply any distinction between the two, he referred throughout his sermon to the husbandman. An anonymous writer published a volume entitled The Rational Farmer and Practical Husbandman in 1745. In 1792 the Rev. John Trusler preached on the Importance, Utility and Duty of a Farmer’s Life, but he too freely referred to husbandmen. To gauge from the titles of their books, late eighteenth-century agricultural authors saw their audience as being farmers: so the Farmer’s Kalender by Arthur Young (first edition 1771), Richard Parkinson’s The Experienced Farmer (1798), William Hogg, The New and Complete English Farmer (1798) and so on.

‘Farmer’, then, is best regarded as an occupational category. Correctly, farmers were people who made their living from rented land and might be distinguished from the more status-based title of yeoman who were, in effect, farmers who owned their land and therefore had a range of political rights.12 But in economic terms, husbandmen are taken to be smaller farmers and yeomen larger ones. The more successful farmers and yeomen probably assumed the title of gentleman. This matter of nomenclature could doubtless be followed much further, and its nuances unpicked. For the moment we can be clear that the word we use probably only adopted its present usage in the eighteenth and was far from universally adopted in the nineteenth century.

As an occupational designation, the term ‘farmer’ covers a wide range of individuals. The point is readily made that farmers were not a homogeneous category of people. Robert E. Brown has already been cited on the range and diversi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Contributors

- 1 Introduction: Recovering the Farmer

- 2 A New View of the Fells: Sarah Fell of Swarthmoor and her Cashbook

- 3 Why Was There No Crisis in England in the 1690s?

- 4 The Farming and Domestic Economy of a Lancashire Smallholder: Richard Latham and the Agricultural Revolution, 1724–67

- 5 The Seasonality of English Agricultural Employment: Evidence from Farm Accounts, 1740–1850

- 6 Farmers and Improvement, 1780–1840

- 7 Farmers of the Holkham Estate

- 8 The Landowner as Scientific Farmer: James Mason and the Eynsham Hall Estate, 1866–1903

- 9 The ‘Lady Farmer’: Gender, Widowhood and Farming in Victorian England

- 10 ‘Murmurs of Discontent’: The Upland Response to the Plough Campaign, 1916–1918

- 11 Rex Paterson (1903–1978): Pioneer of Grassland Dairy Farming and Agricultural Innovator

- 12 Compost in Caledonia: The Work of Robert L. Stuart, Organic Pioneer

- Index