![]() PART I

PART I

Listening Alone![]()

Chapter 1

Death Cab for Cutie’s ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ as Exemplar of Conventional Tonal Behaviour in Recent Rock Music

Walter Everett

Nearly all rock music depends upon the tonal system to which listeners constantly, if unconsciously, compare each example in order to maintain their tonal bearings.1 Some songs, artists and styles adhere more closely to the norms of that system than do others; some are compliant, others adventurous. Frequently, affects tied to a song’s poetic text can be meaningfully found in the shapes and dynamics of particular tonal events. This chapter will aim at relating aspects of voice leading and harmony in Death Cab for Cutie’s tonally conventional yet beautiful and inspiring 2005 song, ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’, to tonal norms so as to provide an understanding of the manifold aspects of its musical structure and to suggest how the song’s poetic concerns are thereby supported and enhanced. If it might seem disappointing at first to scrutinise a conventional structure rather than one more elaborate and potentially more ‘interesting’, I hope that this chapter will prove useful in countering the assertion made by many critics of tonal analysis that rock music does not behave in the same ways as did the much earlier styles that explored and developed the same system underlying tonal relations.2 Despite the subject’s relative simplicity, matters of interest and subtlety will hopefully appear here nonetheless, especially in efforts to suggest how this song and others linked to it may take advantage of many facets of the underlying tonal system in the expression of ideas central to their poetic texts.

‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ has been selected for its intriguing subject matter (the singer’s first-person character represents one member of a couple as he looks ahead to their deaths), its sonic clarity (a single vocal line accompanied by acoustic guitar constitutes the entire texture), its popularity (as a single from the Billboard Top-Five album, Plans, as a song featured in many top-rated television programmes and major motion pictures, and as the subject of several cover versions), its critical acclaim (thumbs up from Christgau n.d. and Pitchfork) and the comprehensibility of its relationship to the underlying tonal system.3 The song’s poetic theme, its sparse texture, its generally diatonic setting and many aspects of its voice leading and harmonic scheme recall all of these aspects of Bruce Springsteen’s contemplative prior ‘If I Should Fall Behind’, and this similarity leads me to begin my project with an investigation of the earlier song. But many details of the musical structure of ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ correspond closely with patterns basic to songs produced throughout rock’s history because they are endemic to the tonal system itself. The strength of these basic events will be demonstrated by showing how most of the characteristic tonal ideas in ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ are also heard in other rock songs of many diverse styles appearing in the two decades surrounding the turn of the millennium.

An Antecessor from Springsteen

An examination of the Springsteen ballad will precede the study of the Death Cab song. ‘If I Should Fall Behind’ was introduced in the 1992 album, Lucky Town, but is perhaps better known as the E Street Band’s quiet closer on their 1999–2000 ‘Reunion’ tour through its appearance on the Live In New York City CD and DVD (both 2001). ‘If I Should Fall Behind’ is a tender, touching and haunting ballad given an acoustic accompaniment (featuring in its studio version a strummed guitar, sustained organ and mandolin) of slow-moving chord changes, sung by its author as a solo except for a few brief double-tracked descant lines that bring prominence to selected phrase endings. Making a pledge of eternal devotion, the singer declares that come what may, he will never leave his beloved. Even though the two may occasionally lose their stride, causing one’s hand to ‘slip free’ of the other’s in the ‘twilight’ (verse 1) and ‘the shadows of the evening trees’ (verse 3), these separations will be only momentary, and the listener infers that death would have no more power over the couple’s inseparability than would the most minor terrestrial intrusions.

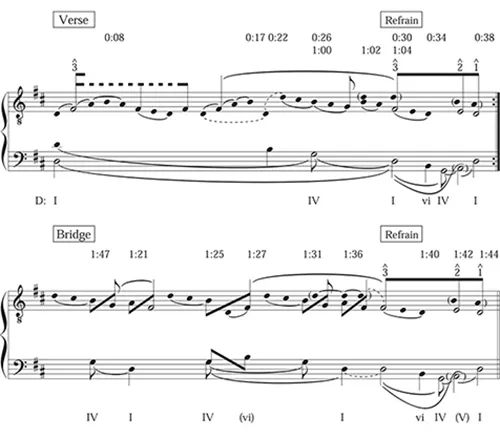

Example 1.1a sketches the voice leading of Springsteen’s vocal parts and the harmonic role of the accompaniment for both the verse and the bridge, the latter of which is performed just once, after the second of three verses (= a classic AABA form). Both sections include the refrain, ‘I’ll wait for you; should I fall behind, wait for me’, allowing for casual variation of the conditional clause as captured in the title. Parenthesised in the treble staff of the graph are the scattered moments of descant harmony; all other pitches shown there belong to the lead vocal. The descant deviations from the lead line suggest both the separation of singer and beloved when their steps fall ‘so differently’ at 1:02–1:04 (the upper voice maintaining the upper first scale degree in oblique motion against the

–

–

fall in the lead vocal) and the unification of the pair with solid fifth doublings (B – A above E – D) of the structural

–

descents in the refrains of the second verse and bridge, replaced by even more unanimous octave doublings on E – D in the coda. At 1:34–1:37 in the bridge’s refrain, the final appearance of a descant part repeats the first scale degree as if a beacon ‘that the other may see’ the couple’s unchanging ultimate goal.

Example 1.1a Voice-leading sketch of Bruce Springsteen, ‘If I Should Fall Behind’ (Lucky Town, 1992)

Example 1.1b

Rhythmic events are not my focus, but I am taken aback by a ‘missing’ measure in the bridge, whose irregular 7 + 8 phrase rhythm is produced by the hypothetical elimination of a single bar of IV, which had begun at 1:25. The expected second bar of this chord is arrestingly elided at 1:27 by an unwelcome minor vi chord at 1:27, portraying the sinister reality of ‘what this world can do’. In the graph a lone unfolding symbol in the tenor range suggests that the B-minor rupture prolongs IV without adding any harmonic value, as if there only for its evocative colour contrast, in recognition of a poetic potential difficulty within the third of the IV chord. Had the parallel unfolded vocal thirds continued throughout the bridge without this disruption below, we might have attained the ideal expressed in the opening line of this section as supported by the IV – I neighbour resolution at 1:17–1:22, by which ‘everyone dreams of a love lasting and true’.

The singer emphasises the fifth scale degree, A, but this is not to be understood as the primary tone for a five-line descent through the G of 0:27 to the F

♯ of 0:30 and beyond. The vocal part instead represents a three-line from primary tone F

♯, made clear by the parallel thirds, A/F

♯ (0:08–0:24) – B/G (0:26–0:29) – A/F

♯ (0:30), that prolong the opening tonic with a neighbouring

, as clarified in

Example 1.1b. The bridge makes this construction even less ambiguous; the same parallel thirds given the unfolding symbols there are interrupted with the stumble of a fourth on the ominous vi chord discussed above. The unfolding of parallel thirds, that is to say the unification of two (mostly) parallel voices in a single vocal part, seems the perfect musical emblem for the lyric’s comforting side-by-side theme.

The verse is based on a descending I – vi – IV arpeggiation (heard twice, as it is repeated in the refrain). This progression introduces the minor vi chord, later to be heard more ominously, as a shadow that first falls over the singer and companion at 0:22 when he acknowledges that the two may ‘lose our way’. The dark root of the vi chord, B, is foreshadowed in the vocal line, in which this sixth scale degree behaves first as a complete neighbour to the fifth of tonic (at 0:08) but then is given autonomy as a non-resolving escape tone from A at the appearance of ‘twilight’ (0:17–0:18). This B at 0:18 truly does exist in twilight: it is a newly emancipated neighbour still consonant above its supporting I chord (and suggestive thus far of nothing darker than the major-pentatonic scale), but in retrospect its value quickly emerges as the germ of the troubling vi to come.

The goal of the descending arpeggiation, IV, does not act as a dominant preparation, but rather as support for the same neighbour resolution to I shown in

Example 1.1b. Tension-bearing dominant harmony makes no appearance in this song; it’s gentle plagal cadences everywhere. In the refrain, however, the strength of the vocal line’s second scale degree at the point of cadence implies where a V might have been expected to appear, and so the graph’s parentheses in the bass line indicate the missing structural element, as the guitar’s IV accompanies what the

singer prefers to render as a ii

chord, altogether realised as IV with added sixth (and elided V).

4‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’: The Song and Its Verse Structure

It is unknown whether members of Death Cab for Cutie knew ‘If I Should Fall Behind’ when Ben Gibbard wrote and recorded ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ as a solo contribution to the group’s 2005 album, Plans, or whether Gibbard has since become aware of any correspondences between the two songs. Regardless of the composer’s intent, there are some relationships that link the songs’ tonal qualities that are of interest given the poetic themes shared by these songs but by no others that come to mind. Death Cab for Cutie (an act named for a song performed by the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band in the Beatles’ 1967 television special, Magical Mystery Tour) is a Bellingham, Washington-born quartet whose first four albums were released on an indie label, Barsuk Records. The last of these, Transatlanticism (2003), was a major hit. The band has had an emo reputation, partly because of their grim name and partly because a melancholy air enfolds some of their thoughtful lyrics; it is also known for its focus on melodic invention. Plans – recorded over the course of a month on a farm outside North Brookfield, Massachusetts – was the group’s first album released after signing with the major label, Atlantic. Debuting at #4 on the Billboard ‘Hot 200’ album chart in August, 2005, and remaining there for 50 weeks, Plans was certified gold by the RIAA in 2006 and platinum two years later. At the time of the album’s recording (following a few changes of drummer), the band was comprised of Ben Gibbard (vocals, guitars), Chris Walla (guitar, keyboards and production), Nick Harmer (bass) and Jason McGerr (drums).

Of Plans, bassist Nick Harmer says, ‘This is a pretty introspective record … There are a lot [more] questions about growing older, responsibility and doubt than there are declarations and answers’ (Hammer, cited in Clark, 2006). Gibbard himself, on the album’s title and theme:

I don’t think there’s necessarily a story, but there’s definitely a theme here. One of my favorite kind of dark jokes is, “How do you make God laugh? You make a plan.” Nobody ever makes a plan that they’re gonna go out and get hit by a car. A plan almost always has a happy ending. Essentially, every plan is a tiny prayer to Father Time. I really like the idea of a plan not being seen as having definite outcomes, but more like little wishes. (Gibbard, cited in Clark, 2006)

Note that this concern over a fateful disruption of planned-for gratification is the same idea phrased at the point of rupture in phrase rhythm and voice leading in Springsteen’s bridge: ‘Now everyone dreams of love lasting and true, oh, but you and I know what this world can do.’ The ‘Death Cab’ in the referential Bonzo song was taking Cutie to her planned destination before she was made to pay the ultimate ‘fare’. The notion of death as fateful interruption that joins the band’s name to the linked demise of both members of a romantic couple in ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ also plays out elsewhere on Plans: the song ‘Soul Meets Body’, in which a bus station is seen as the emblem of a portal to ‘far-off destinations’, includes the line, ‘If the silence takes you, then I hope it takes me too’.

The recording of the understated ‘I Will Follow You Into The Dark’ with a small acoustic six-string was an impromptu affair. Producer Chris Walla recounts the story:

We were going to track the vocal for another song and there was something screwy happening with the headphone mix … We were having problems, so I said, “Ben, this is gonna be a few minutes. Take a break.” Ben’s version of taking a break while we addressed the headphone problem was to pick up this Stella guitar that he loves and start playing this song we were planning on recording some time later during the sessions. He was still coming through the vocal mic as he was playing this, and it was sounding really cool to me, so I went up and said, “Let’s track this real quick”, and we did and that’s what’s on the record. It was a mono recording with no effects. Nothing. I added a little compression and de-es...