eBook - ePub

Local Food Systems in Old Industrial Regions

Concepts, Spatial Context, and Local Practices

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Local Food Systems in Old Industrial Regions

Concepts, Spatial Context, and Local Practices

About this book

In recent years there has been an explosion of interest in local food systems-among policy makers, planners, and public health professionals, as well as environmentalists, community developers, academics, farmers, and ordinary citizens. While most local food systems share common characteristics, the chapters in this book explore the unique challenges and opportunities of local food systems located within mature and/or declining industrial regions. Local food systems have the potential to provide residents with a supply of safe and nutritious food; such systems also have the potential to create much-needed employment opportunities. However, challenges are numerous and include developing local markets of a sufficient scale, adequately matching supply and demand, and meeting the environmental challenges of finding safe growing locations. Interrogating the scale, scope, and economic context of local food systems in aging industrialized cities, this book provides a foundation for the development of new sub-fields in economic, urban, and agricultural geographies that focus on local food systems. The book represents a first attempt to provide a systematic picture of the opportunities and challenges facing the development of local food systems in old industrial regions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Local Food Systems in Old Industrial Regions by Jay D. Gatrell,Paula S. Ross, Neil Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Local Food Systems and Old Industrial Regions

Local food systems and old industrial regions

Economic change, evolving consumer preferences, and the emergence of all things “sustainable” have transformed the lens through which economic geographers and others view industrial regions and the traditional field of agricultural geography. This collection combines traditional industrial geography with agricultural themes informed by sustainability, as well as social justice, to help us understand the emerging local food movement in major urban centers. The book offers two interrelated but arguably distinct sub-fields, “food geography” and “geography of local food systems.” Food geography examines the “food” values, sustainability, and the socio-politics of local food; the geography of local food systems seeks to chart the geography of local supply chains, production, distribution, and associated infrastructures. Most importantly though, both food geography and the geography of local food systems demand increased attention insofar as they have explicit implications for public policy, everyday life, and the socio-spatial politics of inequality (see McEntee and Agyeman 2010). In contrast to traditional geographies of agriculture, these new areas investigate an entirely new collection of inter-related socio-spatial dynamics such as accessibility, consumer decision making, production, race, poverty, community development, sustainability, public health, and economic development policies that shape and define the contemporary foodscape. Consequently, understanding the everyday geography of local food movements, as well as the social context within which local food systems have evolved will inform not only agricultural policy, but social programs and economic development practices, as well as potentially contribute to the transformation of declining industrial regions.

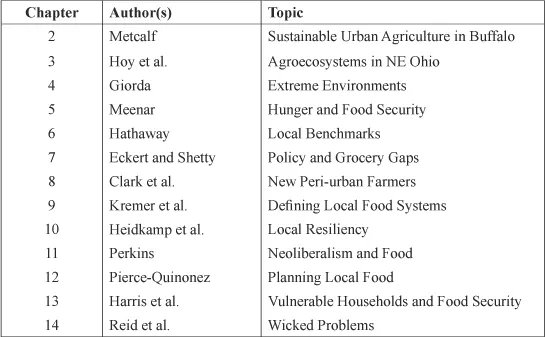

In an effort to chart the nascent geography of local food systems, the International Geographical Union’s Commission on the Dynamics of Economic Spaces organized a residential conference in Toledo, Ohio entitled “Local Food Systems in Old Industrial Regions: Challenges and Opportunities.” As the 2010 international meeting implies, the local food “movement” is one component of a much larger global process that includes discussions of urban agriculture (Zurayk 2010), production capacity (Colasanti and Hamm 2010), market potential (McRae et al. 2010), and even social justice. While the 2010 conference focused on industrial regions, the papers and discussions served as the springboard for this collection—as well as a special issue of Applied Geography—that is much broader than simply a geography of a local food industry. As this collection and the chapters illustrate (see Table 1.1), the socio-spatial dynamics of local food and the conceptual development of the literature continue to evolve and shape the literature on food geography, as well as the geography of local food systems.

This collection contains examples of both food geography and the geography of local food systems. Indeed, the chapters have been selected in large part on the intellectual and conceptual claim each makes relative to food geography or the geography of local food systems, the degrees to which each informs the other, and their collective ability to chart new and interesting research trajectories. For example, in Chapter 2, Metcalf uses a systems approach to understand the conceptual and practical implications of sustainable urban agriculture in Buffalo, New York as an alternative to neighborhood blight, a strategy for improving access to healthy foods, and a mechanism to address poverty. By focusing on “planting the seeds for social change,” Metcalf’s contribution is an example of what we refer to as food geography.

Table 1.1 Chapter topics

Food Geography themes are also the dominant themes in Chapters 4, 8, 11, and 12. Giorda (Chapter 4) presents a novel framework for understanding urban farming as a response to the technological hazards of an industrial economy in the extreme environment of Detroit. For Giorda, Detroit’s urban farms are an intriguing (but arguably inevitable) response to blight, decline, and deindustrialization, and thus are necessarily informed by changing modes of social production, race, and class. Building on the notion of changing modes of production, Clark, Inwood, and Sharp (Chapter 8) investigate how the emergence of new farmers in peri-urban environment has gone “regional” to compete in a new global agricultural space economy. The growth and expansion of local (or regional) food systems have created a new space for startup farmers to successfully compete in urban markets. Yet, as the authors note, the ultimate success of these new farmers (as well as their ideologies) may be at the expense of the traditional family farm. In Chapter 11, Perkins argues that neoliberalism has produced a new local narrative on hunger relief services that shifts the responsibility of hunger relief from society to that of the individual as food producer. That is to say, Perkins argues (echoing themes in Giorda) that urban farming, community gardens, and similar programs enlist hungry urban poor residents within a new local production system that positions hunger relief within a neoliberal hegemonic discourse that makes individuals responsible for their own food security. Pierce-Quinonez (Chapter 12) interrogates local food plans to understand how each promotes (or arguably privileges) distinct and unique definitions of sustainability as either economic, environmental, or social. Using examples from planning, Pierce-Quinonez demonstrates how the development of specific local food systems is inherently linked to the intellectual values that inform them (economic, social, or environmental).

In contrast to food geography, the geography of local food systems charts or assesses the spatial dynamics of economic transactions, local social networks, and other empirically observed connections within and between consumers, producers, and markets. While much of the literature echoes the themes of food geography (specifically class, race, poverty, hunger, and social justice), the focus is on connectivity, production, and consumption. For example, Chapter 3 (Hoy et al.) examines the production potential and overall sustainability of complex (and arguably sustainable) agricultural systems that support urban and suburban populations. Specifically, the authors investigate the bio-geographical potential of northeast Ohio’s agricultural ecosystems to estimate and account for local economic development opportunities, as well as estimate productivity. Meenar (Chapter 5) uses GIS to investigate poverty and hunger in low income neighborhoods—a.k.a. markets. While Meenar uses a planning lens to understand poverty and hunger, his geography of local food systems focuses on the distribution of services associated with hunger relief programs and thus seeks to understand the spatial dynamics and observed patterns of local food distribution networks. In Chapter 6, Hathaway presents a novel framework for assessing the scale and scope of local food systems and the density of local food system “networks” across several declining urban areas. Eckert and Shetty (Chapter 7) consider the policy implications associated with urban food deserts and specifically focus on assessing empirically observed access to food retailers within urban centers, such as Toledo. Charting a so-called “grocery gap,” Eckert and Shetty illustrate the unique challenges facing poor neighborhoods within the context of existing local food systems and identify possible strategies to enhance access within the existing food system.

In addition to chapters that might be defined primarily as either food geography or the geography of local food systems, several chapters interestingly combine both literatures to create a unique contribution that unlocks the inherent contradictions and spatial dynamics of local food systems as a mode of production and response to economic change. In Chapter 9, Kremer et al. use a high tech approach to assess the potential production capacity for community based agriculture across metropolitan Philadelphia. Using GIS and remote sensing, the authors struggle with conceptual definitions of “local food systems” and the inherent responsibility of public institutions to respond to hunger at the individual and household scales. Like Perkins’s Chapter 11, Chapter 9 recognizes that the process of estimating production capacity positions the individual householder as responsible for food security. Similarly, Heidkamp et al. (Chapter 10) examine urban food production as a form of community resiliency in a declining industrial city. In doing so, they recognize that urban farming alone cannot be an effective policy response to hunger or poverty—or the exogenous economic and environmental forces that mandate a community response that ensures food security across the city. Additionally, Harris et al. (Chapter 13) investigate food security in Lewiston, Maine and the unique challenges facing single parent households to access and economically afford nutritional food. In doing so, the chapter demonstrates how the built environment, local markets, and the financial limits of social programs frustrate the food security of the most vulnerable populations.

In addition to the question of urban food systems, all of the chapters in this collection examine key social processes, ideologies, and dynamics that, as Hinrichs (2000) notes, embed local agriculture markets in place. In doing so, the chapters interrogate both local and global narratives on local food, as well as the various ideologies that frame community, institutional, and market responses. As the final chapter demonstrates though, local food systems are only one component of a significantly more complex collection of “wicked problems” situated at the nexus of local and global processes, contested ideologies, and shifting economic conditions. As a result, this collection represents an initial attempt to reconcile observed conditions with the promises and prospects attributed to a larger local food movement. In doing so, this work demonstrates that the emerging geographies of local food (food geography and the geography of local food) are dynamic, multi-faceted, local, and global.

References

Feenstra, G. 1997. Local food systems and sustainable communities. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 12: 28–36.

Hinrichs, C. 2000. Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural markets. Journal of Rural Studies, 16: 295–303.

McEntee, J. and Agyeman, J. 2010. Towards the development of a GIS method for identifying rural food deserts: geographic access in Vermont, USA. Applied Geography, 30: 165–76.

MacRae, R., Gallant, E., Patel, S. et al. 2010. Could Toronto provide 10% of its fresh vegetable requirements from within its own boundaries? Matching consumption requirements with growing spaces. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2010.012.008.

Zurayk, R. 2010. From incidental to essential: urban agriculture in the Middle East. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 1:2. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2010.012.012.

Chapter 2

A Systems Modeling Framework for the Role of Agriculture in a Sustainable Urban Ecosystem

Amidst economic crises, oil shocks, and emerging public awareness of global climate change in an already resource constrained, conflict ridden world, food security has become one of the world’s most pressing problems. This chapter employs a systems modeling framework to explore how sustainable agriculture can alleviate the extreme conditions of poverty and environmental stress experienced in Buffalo, New York and other Rust Belt cities that have an abundance of abandoned property and vacant lots in core urban areas. In the context of a civic engagement with Buffalo’s Massachusetts Avenue Project, a systems modeling framework is developed to integrate sustainable agriculture and local food security. Toward the goals of social and environmental justice, this study is part of a broader effort to match opportunities for urban farms with areas of greatest human need. Identification of feedback relationships from urban farming and food choices informs policy to promote sustainable land use and local food systems.

A common stock

The earth is given as a common stock for man to labor and live on. If for the encouragement of industry we allow it to be appropriated, we must take care that employment be provided to those excluded from the appropriation. If we do not, the fundamental right to labor the earth returns to the unemployed.

(Thomas Jefferson, emphasis added)1

Recognizing the necessity of land for human livelihood, Thomas Jefferson argued in the quoted letter to James Madison that limits should be placed upon appropriation of land that excludes people who depend upon it. As with citizenship, our implicit human right to labor the earth, when recognized, becomes a civic responsibility. Jefferson’s logic of returning the land to its inhabitants has been borne out by the emergence of voluntary “guerrilla gardening” of neglected spaces as a way to overcome property bounds. Guerrilla gardeners seek to wage “war against scarcity and to reconsider land ownership in the quest to “reclaim land from perceived neglect or misuse and assign a new purpose to it.”2

Jefferson’s conception of land as a common stock proves helpful in determining whether or not a system is sustainable, such that stocks of natural resources are not depleted faster than they can be replenished. Because urban land in Rust Belt cities like Buffalo is often neglected and misused, as a shared resource it has been depleted. The challenge is therefore to reclaim and replenish land, finding ways to generate arable land through layers of compost in city spaces. Shared ownership of urban agricultural resources enables more efficient utilization for the common good. This study, based upon a recent civic engagement with Buffalo’s Massachusetts Avenue Project3 [MAP] as well as ongoing interactions with urban agriculture, enables a shift in emphasis from planning per se to planting seeds for change. In this study, a systems perspective is invoked to frame two issues involving human rights and responsibilities in shaping a sustainable urban ecosystem: a) how to equitably satisfy the human right to healthy, local, fresh, and culturally appropriate food; and b) how to exercise the human right to labor the earth in such a way as to restore its ecosystem function.

Massachusetts Avenue Project

The oldest urban farm in Buffalo is operated by the Massachusetts Avenue Project, a neighborhood organization founded in 1992 in response to violent crime on the Lower West Side of Buffalo. MAP began with a focus on food entrepreneurship to expose young people in a distressed neighborhood to opportunities for both economic development and community engagement. MAP’s increasing emphasis on sustainable urban agriculture was outlined in its award-winning “Food for Growth” report, produced collaboratively w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- 1 Local Food Systems and Old Industrial Regions

- 2 A Systems Modeling Framework for the Role of Agriculture in a Sustainable Urban Ecosystem

- 3 Social Networks, Ecological Frameworks, and Local Economies

- 4 Extreme Environments: Urban Farming, Technological Disasters, and a Framework for Rethinking Urban Gardening

- 5 Feeding the Hungry: Analysis of Food Insecurity in Lower Income Urban Communities

- 6 Benchmarking Local Food Systems in Older Industrial Regions

- 7 Urban Food Deserts: Policy Issues, Access, and Planning for a Community Food System

- 8 Local Food Systems: The Birth of New Farmers and the Demise of the Family Farm?

- 9 Defining Local Food Systems

- 10 Urban Food Production Limits and the Viability of Community Gardens: The Case of Hartford, Connecticut

- 11 Neoliberalism and Local Food Systems: Understanding the Narrative of Hunger in the United States

- 12 Planning for Sustainable Food Systems: An Analysis of Food System Assessments from the United States and Canada

- 13 Characterization of the Built Food Environment for Single Parent Households in an Older Industrial City, Lewiston, Maine

- 14 Toward a Relational Geography of Local Food Systems: Or Wicked Food Problems Without Quick Spatial Fixes

- Index