eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Employee Empowerment

Concepts, Critical Themes and a Framework for Implementation

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Employee Empowerment

Concepts, Critical Themes and a Framework for Implementation

About this book

The complexities of employee empowerment have been largely underestimated and it is clear that organisations struggle with putting the concept into practice. Rozana Ahmad Huq recognises that effective utilisation of human resources is a strategic issue for organisations. Hierarchical organisations struggle to survive. The growing trend for downsizing and merging of organisations means that they can no longer maintain the 'command and control' approach and employees are given more responsibility and expected to take decisions. However, simply burdening employees with extra responsibility without empowering them does not deliver results. Drawing on her own research in organisations, Dr Huq investigates the concept of empowerment in a new way that combines themes from the disciplines of management and social work, the latter being a domain where empowerment is an important construct. This helps to bridge the gaps in knowledge in the management domain and draws attention to the positive and negative psychological implications for employees of the practice of empowerment that are often ignored by leaders and managers. Ultimately, the author offers a 'practice model' to help people in management and non-management understand the new roles and behaviours that they need to adopt if empowerment is to become a reality. This book is a resource for any business or other organisation genuinely interested in employee empowerment and for those with a responsibility for teaching about it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Employee Empowerment by Rozana Ahmad Huq in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

What is Employee Empowerment About?

Chapter 1

Concept of Employee Empowerment in the Management Literature

Introduction

Within the context of intense competition, organisations are constantly seeking new sources of competitive advantage. What is required is a model whereby employees ‘at the front lines’ are allocated considerable autonomy and responsibility for decision-making and problem-solving and management exists ‘not to direct and control or to supervise, but rather to facilitate and enable’ (Hammer in Gibson, 1997: 97).

In line with such arguments, organisations responded to the competitive market by attempting to empower their employees; but, there are a number of problems. The first problem is the ‘what’ and the second problem, ‘how?’. In other words, organisations do not grasp the real meaning of ‘what’ employee empowerment means and, second, ‘how’ to implement it?

Another problem is that employee empowerment is often confused with other management initiatives, such as ‘employee involvement’ and ‘employee participation’, and this also contributes to the complexity of implementation. Clearly, these kind of misconceptions can make it difficult for organisations to identify suitable methods and means to implement and sustain the practice of employee empowerment, with the result that ‘its application in organisational settings is fraught with misunderstanding and tension’ (Denham Lincoln et al., 2002: 271) leading to a ‘frustration’ amongst managers (Ford and Fottler, 1995: 22).

My research findings reveal that a number of ‘themes’ of employee empowerment exist, which are fragmented in the management literature. These ‘themes’ are not found in any one place. This lack of information leads to further confusion when organisations try to implement employee empowerment.

This chapter begins by setting employee empowerment in a historical context; ironing out some of the ambiguity and confusion that surrounds the concept and bringing together the themes, under the umbrella of Themes of Employee Empowerment Emanating from the Management Literature, Huq’s Model A (Figure 1.1) that is fundamental to the understanding of it.

Historical Context

A shortcoming of employee empowerment in the management literature is that although there is a plethora of articles and books available on this subject, very few attempt to set it within the historical context (Huq, 2010). Historically, there is neither one single definition of employee empowerment, nor one theoretical construction in the management literature.

There is no single nor simple definition of empowerment. Equally, its prescriptive dimensions cannot be directly traced to any dominant theoretical construction. (Cunningham and Hyman, 1999: 193)

Several authors report that employee empowerment in the 1980s came to prominence as a management response to rapid economic and technological change, and an increasingly complex and competitive external environment (Block, 1987; Peters, 1987; Belasco, 1989; Gandz, 1990; Hammer and Champy, 1993; Hoepfl, 1994; Clutterbuck and Kernaghan, 1995; Lawler et al., 1995; Collins, 1996b; Kondo, 1997; Wilkinson, 1998; Potterfield, 1999; Sigler and Pearson, 2000; Huczynski and Buchanan, 2001; Morrell and Wilkinson; 2002; Psoinos and Smithson, 2002; Greasley et al., 2005).

Authors such as Morrell and Wilkinson (2002: 120) note that employee empowerment is associated with ‘the “excellence” movement, where the customer is “king”. In this sense, empowerment should enable organisations to be more immediately responsive to their customers, as decision-making is devolved’.

‘Productivity through people’, ‘autonomy and entrepreneurship’ summed up the new philosophy which when combined with ‘the customer is king’ provided the context for current empowerment ideas. (Wilkinson, 1998: 42)

Certainly, the quality movement played an important part, underpinning the philosophy of employee empowerment. A number of authors agree that the term employee empowerment came about as organisations were trying to implement initiatives, such as Total Quality Management (TQM) (Lawler et al., 1995; Wilkinson, 1998; Sigler and Pearson, 2000; Morrell and Wilkinson, 2002; Psoinos and Smithson, 2002) and Business Process Re-Engineering (BPR) (Hammer and Champy, 1993; Psoinos and Smithson, 2002; Greasley et al., 2005).

The quality movement was also influential during this period. While its principles had been developed by Japanese companies in the late 1950s and 1960s, interest in the West peaked in the 1980s, and there appeared to be a strong message of empowerment (Wilkinson et al., 1992). Under TQM, continuous improvement is undertaken by those involved in a process and this introduces bottom-up issue identification and problem-solving. As a result TQM may empower employees by delegating functions that were previously the preserve of more senior organisational members. (Wilkinson, 1998: 43)

Empowerment is seen ‘in many respects as a rejection of the traditional classical model of management associated with Taylor and Ford where standardised products were made through economies of scale and the division of labour, and workers carried out fragmented and repetitive jobs’ (Wilkinson, 1998: 44).

A major spur to the popularity of employee empowerment has been the quality movement and, in particular, TQM; both advocate an open style of management, with devolution of responsibility down the line. A key feature of TQM is empowering employees (Crosby, 1979; Deming, 1986; Juran, 1988; Oakland, 1989; Farnham et al., 2005). TQM stipulates that continuous improvement should be undertaken by those involved in a process, thereby introducing elements of bottom-up identification of issues and problems (Wilkinson, 1998; Farnham et al., 2005).

It is also important to note the negative force that has driven the employee empowerment initiative historically, such as rationalisation and downsizing during the 1980s and 1990s. This has created the conception that employee empowerment is for the benefit of organisations only to combat cost-effectiveness and does not relay any benefits to its employees.

In the 1980s and 1990s rationalisation and downsizing were very much the order of the day. In this context empowerment became a business necessity, as the destaffed and delayered organisation could no longer function as before. In this set of circumstances, empowerment was inevitable, as tasks had to be allocated to the survivors in the new organisation. (Wilkinson, 1998: 43–4)

From the human resource management point of view, employee empowerment in the 1990s was underpinned by the notion that competitive advantage can only be achieved by unleashing the power of the workforce (Pfeffer, 1994).

Hence, in general, organisations accept the notion of employee empowerment as a good thing, but in practice struggle with its implementation.

Ambiguity and Confusion

Significant problems regarding employee empowerment range from the vagueness of what it means, to the practicalities of implementing it. ‘Guidelines on making it happen are typically vague and over-generalized’ (Wilson, 2004: 167). Furthermore, this confusion is exacerbated by the ‘interchangeable’ use of the word employee empowerment with ‘employee involvement’ and ‘employee participation’. This gives rise to ambiguity and confusion surrounding it. Hence, ‘a critical analysis of the literature on empowerment does communicate an array of meanings’ (Lashley, 2001: ix).

It is hardly surprising then, that as Ghoshal and Bartlett (1997: 312) point out, in practice, employee empowerment encompasses anything from employee suggestion schemes to the restructuring of the organisation around self-managed teams. It is also argued that different meanings of employee empowerment held by organisations can be problematic, as noted by Clutterbuck and Kernaghan (1995: 7):

it is almost impossible to gain any kind of rational consensus as to exactly what it (empowerment) is. In visiting companies around the world, I have encountered organisations that perceive empowerment to be a total dismantling of the managerial structure in favour of a semi-egalitarian ideal; companies that consider empowerment to be little more than delegation; and others that see it simply as an element of some other change programme, such as total quality management.

It is interesting to note that: ‘Many companies (if not the majority), and the managers and human resource people, within them, do not truly understand what empowerment is or exactly what it entails’ (Pastor, 1996: 7). Hence, in practice, there are problems in implementing employee empowerment, as organisations struggle with the meaning of it. This is illustrated by Lashley (2001: 6):

In the hospitality industry, for example, employee empowerment is a term that had been used to describe quality circles (Accor group), suggestion schemes (McDonald’s Restaurants), customer care programmes (Scott’s Hotels), employee involvement in devising departmental standards (Hilton Hotels), autonomous work groups (Harvester Restaurants) and delayering the organisation (Bass Taverns).

Obviously, if management do not have clarity in their understanding of what employee empowerment means, it can be difficult for them to communicate to employees what they are trying to implement. In the absence of a clear message, the danger is that employees can then formulate their own definitions that, in turn, will influence their expectations (Cunningham et al., 1996; Denham et al., 1997; Morrell and Wilkinson, 2002), which may be different from those of management.

Hence, there is concern not only about the ambiguity regarding the meaning of employee empowerment, but also how employees perceive it, ‘when we talk about empowerment do we all mean the same thing?’ (Burdett, 1991: 23). Another danger is that some managers believe empowering means letting people ‘loose’ on a project as if they are now empowered to do whatever they want (Pastor, 1996: 5). Hales (2000: 503) draws a cautionary note for those who extol employee empowerment’s virtue and highlights the lack of clarity with regards to who is to be empowered and to what extent:

Certainly, the burgeoning prescriptive or celebratory literature on empowerment is replete with equivocation, tautology and contradiction in equal measure about what ‘empowerment’ is, for whom, to what extent, where and why empowerment should occur and what else accompanies it.

Obviously, one of the problems is that organisations are trying to implement employee empowerment without having a great deal of knowledge about this subject.

Unravelling the Mystery

Several authors agree that the concept of employee empowerment in the management literature is diverse and loose (Wilkinson, 1998; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). For example, in Gandz’s (1990: 75) view: ‘Empowerment means that management vests decision-making or approval authority in employees where, traditionally, such authority was a managerial prerogative.’ Authors such as, Huczynski and Buchanan (2001: 262) view autonomy and decision-making to be fundamental elements in employee empowerment, as illustrated: ‘Empowerment is the term given to organisational arrangements that allow employees more autonomy, discretion and unsupervised decision-making responsibility.’ Similarly, Martin (2005: 241) describes empowering employees where ‘Employees are given the freedom (within defined boundaries) to take action without the need to seek approval.’

Interestingly, some authors view employee empowerment simply as a concept or philosophy such as, Ripley and Ripley (1992: 21), who define empowerment as ‘a concept, philosophy, set of organisational behavioural practices, and an organisational programme’. According to other authors, distribution of power is fundamental in employee empowerment (Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Bolin, 1989; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990).

Expanding on Conger and Kanungo’s (1988) study, Thomas and Velthouse (1990: 677) identify employee empowerment from the psychological point of view and describe it as: ‘an emerging, non-traditional paradigm of management’ and further go on to stress: ‘We have argued that the motivational content of this paradigm involves the fostering of intrinsic task motivation among workers.’ Thus, employee empowerment is also viewed as a psychological concept leading to intrinsic motivation (Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990; Siegall and Gardner, 2000) and self-efficacy (Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990; Spreitzer, 1995, 1996; Hartline and Ferrell, 1996; Heslin, 1999; Siegall and Gardner, 2000).

These different meanings of employee empowerment held by organisations can be problematic, as noted by Clutterbuck and Kernaghan (1995: 7):

it is almost impossible to gain any kind of rational consensus as to exactly what it is. In visiting companies around the world, I have encountered organisations that perceive empowerment to be a total dismantling of the managerial structure in favour of a semi-egalitarian ideal; companies that consider empowerment to be little more than delegation; and others that see it simply as an element of some other change programme, such as total quality management.

Clearly, such confusion and ambiguity have implications for organisations seeking to implement employee empowerment. The term employee empowerment does have a number of themes attached to it and therefore it produces a number of meanings.

As already mentioned, employee empowerment is blamed for communicating an array of meanings. At the outset, employee empowerment does seem mysterious with so many different interpretations accompanying it. In reality, there is no mystery regarding employee empowerment; simply, a multi-dimensional approach is necessary with regards to understanding the notion of employee empowerment. It is not possible to capture the essence of empowerment in a single concept (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990).

Honold (1997: 210) rightfully states: ‘it seems that employee empowerment is multi-dimensional. No single set of contingencies can describe it.’ In a similar tone, authors such as Greasley et al. (2005) are also in agreement and they too assert the need for a multi-dimensional approach, particularly in order to sustain the employee empowerment strategy in organisations. This is what is largely missing with regards to employee empowerment in the management literature; the fact that it has more than one dimension or themes and that all of these themes need to be considered.

In this book, I have attempted to pull the themes of employee empowerment from the management literature discussed next.

Themes of Employee Empowerment Emanating from Management Literature: Huq’s Model A

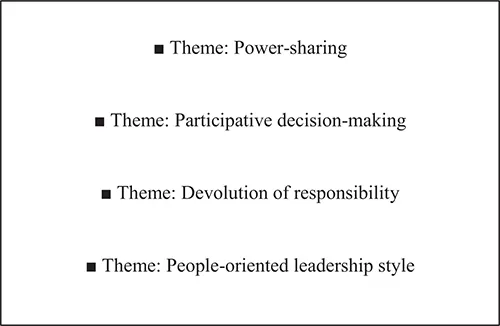

It is agreed that a number of themes surround employee empowerment. A review of the management literature highlights power-sharing; participative decision-making; devolution of responsibility and people-oriented leadership style – Huq’s Model A (see Figure 1.1). These are some of the key themes of employee empowerment emanating from the management literature.

Figure 1.1 Huq’s Model A: themes of employee empowerment emanating from management literature

It is evident that employee empowerment is not viewed as a one-dimensional management practice, there are several themes associated with it. The importance and significance of these aforementioned themes are explained next.

Power-Sharing

The Concise Oxford Dictionary’s (p. 339) definition of ‘empower’ is to ‘give power’, thus to ‘empower’ is to:

Authorise, license, (person to do);

Give power to, make able, (person to do).

Give power to, make able, (person to do).

In the literal sense, empowerment is about giving power. This needs to be highlighted, and several authors do this. For example, Lashley (2001) emphasises that the power dimension is fundamental to understanding the concept of empowerment. Dupuy (2004: 217) recognises that to empower is to acquire ‘more power’, which is the literal translation of the word ‘empowerment’. Other authors, such as Wilson (2004: 167), stress that in order to empower employees, power needs to be shared: ‘it concerns an individual’s power and control relative to others, as well as the sharing of power and control, and the transmitting of power from one individual to another with less’. In a similar vein, Neumann (1992/3: 25) defines empowerment as ‘passing on previously withheld power and authority to employees further down the hierarchy’.

There is agreement in the literature that the distribution of power is more important than the hoarding of power (Kanter, 1984; Goski and Belfry, 1991; Daft, 1999; Greenberg and Baron, 2000). It makes sense to give employees power, especially ‘to make certain decisions and resolve certain issues themselves’ (Lashley, 2001: 7). But, the question is does this really happen in organisations? The problem is that management hide their heads in the sand when it comes to power-sharing, despite the fact that it is widely agreed that power-sharing is an essential part of employee empowerment (Kanter, 1984; Block, 1987; Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Bowen and Lawler, 1992; Martin and Vogt, 1992; Neumann, 1992/3; Ashness and Lashley, 1995; Hardy and Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1998; Wilkinson, 1998; Daft, 1999; Quinn and Davies, 1999; Greenberg and Baron, 2000; Lashley, 2001; Denham Lincoln et al., 2002; Dupuy, 2004; Wilson, 2004).

But, there are tensions and often conflict surrounding the sharing and distribution of power. Undoubtedly, in empowered organisations, power structures will be challenged. Lashley (2001: 160) notes: ‘empowerment essentially implies that organisational power structures are being altered so as to allow individuals (operatives or managers) more power.’ The removal of hierarchies and the implementation of flat structures in empowered organisations give rise to some questions, such as, what happens to power held by people and how is it shared, if at all? These are challenging questions for empowered organisations where employees expect managers to be flexible in their sharing of power. But, the literature does not provide clear information on how management should share power and management feel they are caught in a dilemma because they are not sure how they can do this, without diminishing their own power (Tjosvold et al., 1998).

The ambiguity concerning the meaning of employee empowerment is seen by some authors, such as Edmonstone and Havergal (1993), to be perhaps an unfortunate source of ambivalence among managers. They may see employee empowerment as a structural form of control as far as workers are concerned. Fincham and Rhodes (2005: 430) conclude that traditional organisational hierarchies are ‘structures of deeply entrenched power, and this has also proved to be a major constraint on work humanization’. Often, people with power at the top, such as leaders or chief executives, are uncomfortable with changes, and feel so threatened by the fear of losing their control, that proje...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- Part I What is Employee Empowerment About?

- Part II What Does Social Work Have to Do With It?

- Part III What Does Psychology Have to Do With It?

- Part IV From Boardroom to Factory Floor ‘Let the Data Speak!'

- Part V Does it Deliver?

- Part VI Changing Role of Leaders

- Part VII Huq's Model of Employee Empowerment

- Bibliography

- Index