- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England

About this book

Funeral monuments are fascinating and diverse cultural relics that continue to captivate visitors to English churches, yet we still know relatively little about the messages they attempt to convey across the centuries. This book is a study of the material culture of memory in sixteenth and seventeenth-century England. By interpreting the images and inscriptions on monuments to the dead, it explores how early modern people wanted to be remembered - their social vision, cultural ideals, religious beliefs and political values. Arguing that early modern English monuments were not simply formulaic statements about death and memory, Dr Sherlock instead reveals them to be deliberately crafted messages to future generations. Through careful reading of monuments he shows that much can be learned about how men and women conceived of the world around them and shifting concepts of gender, social order and the place of humans within the universe. In post-Reformation England, the dead became superior to the living, as monuments trumpeted their fame and their confidence in the resurrection. This study aims to stimulate historians to attempt to reconstruct and engage with the world view of past generations through the unique and under-utilised medium of funeral monuments. In so doing it is hoped that more light may be shed on how memory was created, controlled and contested in pre-modern society, and encourage the on-going debate about the ways in which understandings of the past shape the present and future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England by Peter Sherlock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Family Fictions

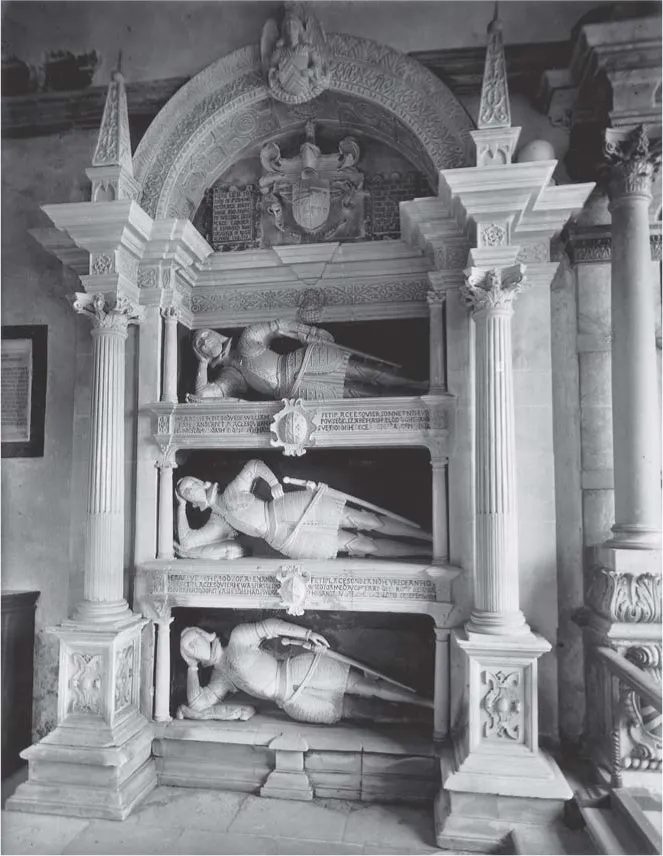

One of the most loved and well-known tombs from the early modern period is the quirky monument representing three generations of the Fettiplace family at Swinbrook, a parish in rural Oxfordshire. The memorial, on the north wall of the chancel, is composed of three tiers surrounded by elegant columns and crowned by a generous arch. Three effigies represent Sir Edmund Fettiplace (d. 1613), below him his father William (d. 1562) and at the base his grandfather Alexander (d. 1504). The visual impact of this striking tomb is memorable. Pevsner described the style as ‘primitive classicism’ with each figure ‘painfully reclining on an elbow’ and displayed ‘like merchandise in a shop’.1 The whole effect is heightened by a second monument to the east of the first, which displays a further three generations of rather more portly Fettiplace men and brings the pedigree through to the 1680s.

The monument’s inscriptions and its mannequin-like effigies do not tell us much about the Fettiplace family or its individual members. The form and location communicate the family’s pride in the longevity of their line, their power in Swinbrook and surrounds and the triumph of memory over death. The heraldic shields grow in size as the tiers ascend, culminating in a large achievement under the arch, thereby suggestive of the family’s increasing significance and deepening connections over time. On either side of the uppermost coat, an epitaph reminds the viewer of the family’s bright future: Sir Edmund’s wife insured his posterity by producing no less than 12 sons and seven daughters.

The tomb was commissioned in detail by Sir Edmund in his will. After making provision for his 13 surviving children, he bequeathed 20 pounds towards ‘a tombe to be made in the Church at Swinbrooke for my Graundfather my Father and my selfe wth three degrees, and severall inscripcons and wth three severall pendaunts and Coate: armors’.2 His widow Anne and eldest son John completed the tomb in their capacity as his executors. They also erected a verse epitaph on the wall beside the tomb to demonstrate their dutiful adherence to the terms of the will and to indicate their love and sense of loss. Amongst other qualities Sir Edmund was:

1.1 Monument of Edward Fettiplace (d. 1613), Swinbrook, Oxfordshire. Reproduced by permission of English Heritage. NMR.

Blessed in soule, in bodie, goods, and name,

In plentieous plants by a most vertuous dame,

Who with his heire as to his worth still debter,

Built him this toomb, but in her heart a better.

The Fettiplace tombs at Swinbrook may be read superficially as signs of a family intent upon commemorating the passing of six generations of men over a period of two centuries. Yet they are self-evidently the result of two commissions undertaken some 70 years apart. The commitment of individuals such as Sir Edmund and his widow to commemorating themselves and their ancestors underscores the dominance of lineage as a theme in the motivation behind early modern monuments. As a matter of course, tombs identified their subjects’ parents, partners and progeny, and sometimes more remote family members. Purpose-built chapels, former chantries, manorial aisles, chancels and even sanctuaries might be filled with series of monuments depicting several generations of the one family, conveying the continuity of lineage and land tenure in spite of the destruction wrought by death and time on mortal flesh.3 Some monuments even took the form of family trees, such as the brass to seven generations of the Beale family erected at Maidstone, Kent in the 1590s, or the St John triptych at Lydiard Tregoze, Wiltshire. Such messages were convenient if necessary political fictions that paraded continuity and antiquity where it did not always exist.4 In so doing, they naturalised and legitimised the exercise of power by a male patriarch over his household and manor, and by one family over its neighbours.

This chapter investigates how lineage was represented in tombs, including posterity as well as ancestry. It challenges the idea that monuments were commonplace objects automatically erected by the gentry and nobility to convey formulaic messages. The representation and construction of lineage is studied in two ways: first, by the examination of a single space dedicated to a family’s monuments and second, by investigating the memorials commissioned by a single person in a range of places. Both examples come from the English nobility. While broadly similar instances can be found amongst the gentry, the nobility were not hostage to primogeniture in quite the same way, since a title might survive the failure of a male line. Antiquity and continuity were bestowed upon nobles by the proper noun appended to their peerages and not by blood or land alone. Lineage was nevertheless still a fiction, for most family chapels were the work of one or two committed descendants who erected several tombs, rather than the result of each generation commemorating its immediate predecessor over a long period of time. Moreover, by memorialising their kin, these individuals attempted to control, rewrite and even fabricate their family histories, to give their posterity as much advantage as possible in a society that remained preoccupied with ancestry throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.5

The visual impact of objects like the Fettiplace monuments have led art historians such as Eric Mercer to assert that ‘by about 1600 it was almost de rigueur for a landed family to have a series of magnificent tombs in the local church’.6 Despite the existence of thousands of early modern tombs in English churches today, the quantitative reality of commemoration does not support this view. In fact, the burial places of a majority of England’s elite were not marked by stone, brass, glass or wood. To take the most extreme example, no contemporary monument was erected to an English monarch from the completion of Queen Elizabeth’s tomb in 1606 until Victoria built her mausoleum in the wake of Prince Albert’s death two and a half centuries later. (The exception is a tablet in France for the unfortunate James II.) Prior to Elizabeth we encounter monuments to Henry VII and Edward VI (the latter destroyed in the 1640s), but none were finished for Mary, Henry VIII or Edward IV. Llewellyn accounts for this remarkable absence of royal sepulchres by the ‘negative tension’ caused by the increasing size and quality of monuments generally: royal tombs had to be the most magnificent of all but the artistic and financial resources available to the crown after 1600 were limited.7 Nevertheless, if monuments were intended to preserve continuity in the face of death and assert the unbroken succession of titles and estates, then this absence of royal tombs is problematic to say the least.8

The tendency of the majority of sovereigns to lie uncommemorated was reflected in the burial practices of the English nobility. The 13 volumes of the Complete Peerage record just over 2,000 English peers and their consorts who died between 1400 and 1700. The editors of this work were remarkably comprehensive in identifying not only the existence of monuments that have survived to the present but also those that survive only in the pages of early modern county histories and antiquarian manuscripts. Over these three centuries, some 2,075 nobles or their spouses died, of which 1,004 had no known grave marker. A further 626 probably had no monument, while 445 definitely did. In short, at worst one-fifth and at best half of the nobility were commemorated in material form; the actual figure is probably about one-third. When these data are broken down into shorter periods, the most intensive commemorative activity is revealed to have taken place between 1580 and 1640. Even in these decades, however, only 124 of the 382 peers and consorts who died definitely had monuments, while 192 did not, with the fate of the remaining 66 uncertain. It is thus safe to say that a majority of the early modern nobility were buried without the provision of permanent grave markers.9

Once this is acknowledged, the question becomes why some nobility did erect tombs, rather than why others did not. Far from being formulaic objects built by most wealthy people, tombs had specific purposes and were constructed with particular outcomes in mind. It is more useful to investigate the motivations behind those monuments that were built rather than attempting to explain why, for example, some Tudor and Stuart monarchs and a majority of the nobility were laid to rest without them. For the absence of tombs cannot be attributed simply to neglect or post-Reformation iconophobia. Monuments, after all, were relatively cheap objects in comparison to elaborate houses, or the expensive but more ephemeral clothing embraced by the aristocracy.10 For example, although James VI and I spent some £3,500 on tombs for his mother, predecessor and daughters in Westminster Abbey, placing them in the very top bracket of expenditure on monuments, his annual clothing budget was in the tens of thousands of pounds.11

Those nobles who did build monuments made much of their lineage, extended kin and the succession of titles across time. One of the reasons why the early modern nobility appears to be extensively memorialised is the existence of several family chapels packed with monuments to successive generations of lords and ladies, such as those of the Spencers at Great Brington or the Earls of Arundel in Sussex. These mostly took shape from the mid-sixteenth century as the dissolutions of monasteries and chantries forced families to relocate ancestral monuments to safer environs, make use of remaining spaces in parish churches for commemorative purposes, or look further afield for burial grounds.12 The continuation of a family line and the maintenance of its power were subject to war, illness and genetics. The representation of continuity between an ancient lineage and the hopes for posterity was frequently an attempt to create a reality, rather than reflect it.13 The desire is clearly seen in the ten matching tombs commemorating 200 years of Pointz ancestors at North Ockenden, Essex, erected in about 1606 and using progressively antiquated costumes to achieve the effect of antiquity.14

The most comprehensive and impressive series of noble tombs in England is that of the Earls and Dukes of Bedford in the chapel attached to the parish church of Chenies, Buckinghamshire. Indeed, Pevsner described the Bedford chapel as ‘the richest single storehouse of funeral monuments in any parish church of England’.15 The Russell family tombs reveal a complex pattern of commemoration. Patronage occurred sporadically across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the results exhibit a much broader sense of lineage than the simple succession of father and son to lands and titles. An inscription at the chapel tells us that it was founded in 1556 by Anne Sapcote (d. 1559) to commemorate herself and her third husband, John Russell (d. 1555), the first Earl of Bedford. Anne had inherited the manor of the Cheyne family, to whom it had belonged for three centuries. The manor passed from the childless Agnes, Lady Cheyne, to her niece Anne Phelip, who was mother of Anne Sapcote. Monumental brasses seeking intercessions for the souls of Agnes, Anne and their various husbands already existed at Chenies. The new chapel may have been strategically designed to consolidate the Russells’ rather tenuous control of the manor. Four years after its construction, the family secured its hold on Chenies by obtaining a formal conveyance of rights to the manor from their distant relation John Cheyne, the heir male under lady Cheyne’s will.16

1.2 The Bedford Chapel, Chenies, Buckinghamshire. © His Grace the Duke of Bedford and the Trustees of the Bedford Estates.

The monument to the first Earl and Countess was placed towards the east end of the chapel in the centre of the pavement, the principal position in traditionalist geography. The tomb’s components were more ambiguous in religious expression, reflecting the pragmatism of a man who employed Miles Coverdale as a chaplain in Edward’s reign and was a friend of Abbot Feckenham in Mary’s. The tombchest was decorated in a Renaissance idiom, perhaps prompted by the Earl’s e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Family Fictions

- 2 Monumental Bodies

- 3 Life and Death

- 4 Reformation

- 5 Renaissance

- 6 Law and Order

- 7 Word and Image

- 8 Memory

- Bibliography

- Index