eBook - ePub

Knowledge-in-Practice in the Caring Professions

Multidisciplinary Perspectives

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Knowledge-in-Practice in the Caring Professions

Multidisciplinary Perspectives

About this book

Knowledge-in-Practice in the Caring Professions explores the nature and role of knowledge in the practical work of the caring professions. It focuses on knowledge of the practical over the theoretical, looking at the application of theory and the implementation of skill, judgment and discretion. Containing contributions from experts in a variety of fields, the research within this book offers a unique perspective on professional practice as multi-disciplinary, illustrating shared and overlapping understandings in knowledge-in-practice between the different professions as well as understandings that are distinctive to each discipline. It underlines that in order to effectively address the range of social, psychological and health problems facing contemporary societies, professionals need to engage in cooperative models of practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Ideas of knowledge in practice

The specialized practice of caring professionals comprises several cognitive dimensions. The most obvious of the dimensions consists in theories, understandings, experiences, facts, advisory rules, stipulations and other such items as have been expressed as formulated knowledge, this knowledge serving as a resource from which agents draw in guiding their practice. The concept of formulated knowledge points to a broad distinction between theory and practice, which has been drawn from the time of ancient Greek philosophy (Lobkowicz 1967). Textbooks are the obvious bearers of formulated knowledge in the training of the professional. Some of the formulated knowledge that she acquired in her professional training may eventually disappear from the practitioner’s view, perhaps on account of its having become obsolete, second nature, or having fallen into disuse. Articles in journals and papers at conferences are sources of formulated knowledge with which the professional can supplement her textbook knowledge, inform her practice and keep herself up to date. Theorists have lavished attention over many years on the topic of formulated knowledge and its involvement in professional practice. Relatively little will be said about knowledge of this type in this chapter, one theory being noted to illustrate how such knowledge may come to be produced and used.

The philosopher Karl Popper (1902–1994) advanced a metaphysical theory of three worlds: the physical and the psychological (subjective) – worlds one and two, respectively – and the world of objective products, including language, and knowledge which is formulated in language as affirmations (or denials) of facts and theories and prescriptions of rules and values (Popper 1972: 118).

Complementing his three worlds view, Popper presented a theory the skeleton of which is rendered as PP1→TT→EE→PP2, signifying that the human agent is constantly having to solve problems of one sort or another (for example, technical difficulties, practical issues, explanatory questions) (PP1), by conceiving of theories, framing policies and devising innovative courses of action (designated as TT).1 As explained by Popper, criticizing (EE) a tentative solution (TT) to one problem might expose it as unsatisfactory, which produces a new problem, question or difficulty (PP2) and a further sequence (TT2→EE→P3). Chiefly interested in knowledge that is formulated and objective, Popper envisaged it as an external resource that is produced by scientific researchers, of which the caring professional avails himself in his problem-solving work, seeking, in the words of Schön (1983: 147), to transform ‘the situation from what it is to something he likes better’. The problems that professionals encounter in their practice are of different degrees of difficulty, their solutions calling for more or less inventiveness. New problems may be encountered and preexisting solutions may have to be applied in unusual circumstances.

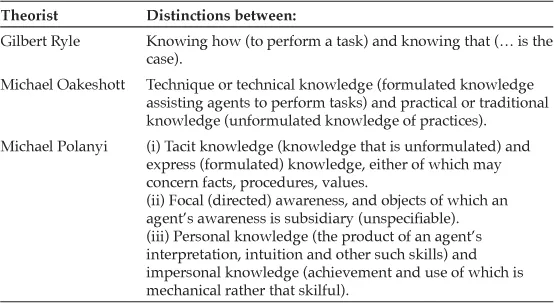

More directly relevant to the theme of this book is the unformulated knowledge that professional practice embodies. To better understand this rather remote subject, it will be helpful to view it from different vantage points, bringing its more important features into clearer focus. Three theories of embodied knowledge receive pride of place in this chapter, theories that, having exerted a lasting and pervasive influence, deserve the honorific adjective, ‘classical’. They are summarized in Table 1.1

Table 1.1 Theories of embodied knowledge

We should note that the term ‘practice’ is ambiguous between, on the one hand, the activity of individual agents and, on the other, inclusive social processes comprising the activities and culture (language, knowledge, traditions, presuppositions) of social groups. The second notion of practice is represented by Michel Foucault (1991) who envisaged practices of medicine, jailing, psychiatry and nursing as disciplining members of modern society: people’s bodily demeanours and dispositions, vocabularies and worldviews, perceptions and understandings. The two concepts of practice complement each other, but this chapter principally studies the practice of individuals as that which is more directly relevant to the subject of this book. (The more inclusive concept of practice – found also in the tradition of Emile Durkheim, and in the writings of Pierre Bourdieu – is well discussed by Schatzki et al. 2001, see also Filmer 1998: 230–33.)

Knowing how

A distinction has been drawn in the philosophical literature between knowing that (indicative knowledge) and knowing how (practical knowledge). The idea of knowing how appeared in Greek philosophy, and the Chinese Taoist philosopher, Chuang Tzu (399–295 BC), expressed it when he quoted a wheelwright who appreciated that his work needed to be done at ‘the right pace, neither slow nor fast’ and this, he observed, ‘cannot get into the hand unless it comes from the heart. It is a thing that cannot be put into words ... there is an art in it that I cannot explain to my son’ (quoted by Oakeshott 1991: 14, n.7). Practical knowledge has been analyzed by American pragmatist philosophers, including William James (1842–1910) and John Dewey (1859–1952), with Smith observing (1988: 15, n.2) that it probably was Dewey who explicitly introduced the opposition between knowing how and knowing that into the modern philosophical literature. Thus in his Human Nature and Conduct (1922: 178) Dewey identifies knowing how with habitual and instinctive knowledge, to be contrasted with knowing that things are thus and so, which ‘involves reflection and conscious appreciation’.

The knowing that/knowing how distinction was most famously explicated in the twentieth century by the Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1900–1976), in his book The Concept of Mind (1949). Ryle’s overriding aim was to show that, when using mental adjectives (for example, ‘efficient’, ‘competent’, ‘skilful’, ‘committed’, ‘ignorant’, ‘erratic’, ‘slipshod’ and ‘unskilled’), we are referring not to what occurs in the consciousness of people, to processes taking place in some special entity or ‘organ’ ‘in the head’, but to public actions (Ryle 1949: 40, 50–51, 61). Explained Ryle (1949: 51, also 50, 54, 58), we are describing, not ‘occult causes’ but dispositions that people have, exercise and manifest by way of their conduct. Bodily performances ‘are not clues to the workings of minds; they are those workings. Boswell described [the workings of] Dr Johnson’s mind when he described how he wrote, talked, ate, fidgeted and fumed’ (Ryle 1949: 58).

Ryle considered that the common view of mental activity gave pride and place to cognition and to problem solving. This type of activity, described by Ryle (1949: 26) as ‘theorizing’ is, in the common view, designed to achieve ‘knowledge of true propositions or facts’, as exemplified by knowledge in mathematics and the natural sciences. ‘Theorizing’ is commonly construed as a ‘private, silent or internal operation’ (Ryle 1949: 27).

Paying disproportionate attention to analyzing the sources, nature, and validation of theoretical knowledge, philosophers have, Ryle suggested (1949: 28, emphasis added), insufficiently explored ‘what it is for someone to know how to perform tasks’, this knowledge consisting in people’s talents, competences, abilities and skills. In Ryle’s interpretation (1949: 28, 41), to state that a person knows how to perform a task of a particular type implies that she performs it ‘correctly or efficiently or successfully’, the agent regulating her performance by observing relevant rules (‘bans’, ‘permissions’) and applying correct standards. There is an ‘intellectualist legend’, rejected by Ryle, according to which intelligent conduct is preceded by a thoughtful consideration of how best to proceed, what rule to follow. Argued Ryle (1949: 32),

‘thinking what I am doing’ does not connote ‘both thinking what to do and doing it’. When I do something intelligently, i.e. thinking what I am doing, I am doing one thing and not two. My performance has a special procedure or manner, not special antecedents.

The performance is skilful, and a skill is ‘not an act’, nor an event, but a disposition (tendency) on the part of a person to conduct herself in a certain way in situations of a given sort (Ryle 1949: 33, 40). A disposition is, for Ryle (1949: 34), an agent’s ‘mind at work’.

Ryle noticed different ways in which a skill can be acquired, including explicit instruction in the rules that govern it. Having mastered the rules of the skill by rote, an agent may be able to express them upon request. But in complying with the rules of the activity, Ryle believed, an agent typically follows the rules without thinking of them (although she does think about what it is that she happens to be doing).

A trainee can also ‘pick up the art’ of how to perform a task by observing conduct that is exemplary of it without ‘hearing or reading the rules at all’, the acquisition of rudiments ‘of grammar and logic’ being a case in point (Ryle 1949: 41). The agent has to practise the repertoire if she is to master the conduct and the rules it incorporates. Ryle wrote (1949, 41), ‘we learn how by practice, schooled ... by criticism and example, but often quite unaided by any lessons’ in a corresponding theory or rules. Graduated tasks are set for the student; each set of tasks being achievable by her but challenging her more than the last. The training may involve repetitive drill, but since the aim is to have her incrementally improve her performance, the trainee will be encouraged to extend her thinking and to sharpen her judgement (Ryle 1949: 42–3). Subjected to criticism (and self-criticism), each task ‘performed is itself a new lesson to him how to perform better’ (Ryle 1949: 43). The test of whether Ryle’s trainee has acquired the knowledge of how to perform some kind of task consists not in her being able to formulate and express the guiding rules but in her conforming to them in competently enacting the task. An agent’s knowing how to perform a task is not to say she can give a detailed verbal description of the performance. In much of her activity the social worker, psychotherapist or other caring professional conforms to rules and uses criteria without being conscious that she does so (Ryle 1949: 48).

Some of the competent practice of caring professionals may become habitual, which is to say blind and repetitive. Usually, however, their practice involves a disposition to exercise an ‘intelligent capacity’, meaning that an agent gives thought to her task. It is a characteristic feature ‘of intelligent practices that one performance is modified by its predecessors’; the agent continues to learn and aims to do better (Ryle 1949: 42, also 48). The caring professional, for example, is called on to handle ‘emergencies’, to carry out ‘tests and experiments’, to interpret new or unusual evidence, and to make new connections between experiences. She has to innovate and adapt. Exercising ‘skill and judgement’, Ryle’s agent (1949: 42) aims to avoid making mistakes, and wishes to learn from any that she does make. In Ryle’s words (1949: 49), ‘A man knowing little or nothing of medical science could not be a good surgeon, but excellence at surgery is not the same thing as knowledge of medical science; nor is it a simple product of it’. Besides having been taught the formulated knowledge of his profession, a surgeon ‘must have learned by practice a great number of aptitudes’. In the practice of the caring professional, rules have to be applied, and ‘putting the prescriptions into practice’ calls for intelligence of a different kind from that which is involved in learning and understanding the formulated prescriptions.

Knowing how is, Ryle noticed, relative (whereas knowing that – say, that Jupiter has 63 moons or that the British settled in Sydney in 1788 – is absolute) in the sense that cases of it occur across a spectrum, ranging from ignorance to complete knowledge. No caring professional acquits herself perfectly (with complete knowledge of both kinds) in any of her professional activities.

Technical and practical knowledge

Inquiring into modern rationalism as a style of political thinking, in a 1947 essay, ‘Rationalism in Politics’, the British political theorist Michael Oakeshott (1901–1990) envisaged knowledge as a part of each and every activity (the sciences, and the arts, among others). Although his essay appeared after Ryle’s first published investigation in 1946 of the distinction between knowing how and knowing that, Oakeshott made no mention of, and may not have seen, Ryle’s discussion. Among the few authors Oakeshott cited in ‘Rationalism in Politics’ was Michael Polanyi, whose ideas we will consider shortly.

Oakeshott (1991: 12) separated out two types of knowledge involved in human activity, while recognizing that in any ‘concrete human activity’ the types occur inseparably intertwined. Oakeshott described one of the types as ‘technical knowledge or knowledge of technique’ or simply as ‘technique’ (1991: 12 emphasis added). He considered that knowledge of this type lends itself to being formulated in propositions (‘rules, principles, directions, maxims’) that agents can study, recall and apply (1991: 14). His examples of formulated technique range from the homely (knowledge expressed in cookery books), to the esoteric (rules of research in science and in history). Oakeshott (1991: 12) designated the second type of knowledge as ‘practical’, otherwise referring to it as ‘traditional knowledge’. This knowledge, Oakeshott argued (1991: 15), is expressed ‘in a customary or traditional way of doing things’ (a ‘practice’), and in discriminations of ‘taste or connoisseurship’ that agents make in their enactment of a practice. In Oakeshott’s account, no skill or practice is acquirable without a dimension of traditional/practical knowledge, and no task can be performed by an agent who has a command of relevant technique and of formulated rules but is without the practical knowledge of the tradition.

Oakeshott (1991: 15) looked on each form of knowledge as transmitted and received in its own way. Technical knowledge is conveyed in textbooks and lectures, being ‘taught and learned’ (1991: 15), whereas practical knowledge exists only in the activities that actualize a practice and it cannot be verbally transmitted. Because it is unformulated, Oakeshott reasoned (1991: 15) that practical knowledge must be ‘imparted and acquired’, each generation of practitioners having to be trained as apprentices to ‘master[s]’, observing and emulating the skill of accredited craftsmen, acquiring practical knowledge and technique together. In regard to the ‘human arts’, which have people ‘as their plastic material’, it is, Oakeshott suggested (1991: 13 emphasis added), a mistake to imagine that technique indicates ‘what’ the midwife, or doctor, psychologist, nurse, or social worker is to do, and to assume that practice guides her on ‘how’ to proceed. ‘Even in the what’ (for example, the diagnosis of a condition, the classification of a behaviour, deciding on the best treatment or the appropriate response), the ‘dualism of technique and practice’ is already present (Oakeshott 1991: 13). There is, according to this view (1991: 14–15), no knowledge that is devoid of ‘know how’. Would a Gilbert Ryle have agreed with this generalization of Oakeshott? Given that Ryle distinguished between ‘knowing that’ and ‘knowing how’, there has to be, in his view, some appreciable difference between them. He might have allowed that the distinction is artificial in as much as each instance of an agent knowing that, in some concrete discipline or practice, incorporates an element of knowing how (if only subordinately). For example, a proficient chemist who knows that Boyle’s gas law is PV=k also knows how to do the calculations that are needed to apply the law. Nonetheless, Ryle would probably have disagreed with Oakeshott, arguing that, in real concrete disciplines and in situations in which professionals act, knowing that differs in its emphasis and purpose from knowing how, including more of indicative (descriptive or explanatory) knowledge and less of practical knowledge (of how to proceed). Conversely, for Ryle, knowing how differs in its emphasis and purpose from knowing that, being primarily practical knowledge (about the way in which an agent needs to proceed in her execution of a particular task), with indicative knowledge in a subordinate role. In this manner, one surmises, Ryle would have considered Oakeshott’s ‘all knowledge is “know how”’ to be a confused and confusing statement.

At around the time of the appearance of these works by Ryle and Oakeshott, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), a professor of philosophy at Cambridge University in the 1940s, was formulating ideas of a similar nature to theirs. In the posthumously published work On Certainty (1974), Wittgenstein argued that, as members of ‘a community which is bound together by science and education’ (1974: § 298), our cultural endowment includes a ‘picture of the world’ (Weltbild) (1974: § 94). The world picture is not an object of thought and examination for members of a community, their thinking being embedded in, and impossible without, this usua...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Ideas of knowledge in practice

- 2 Information, knowledge and wisdom in medical practice

- 3 The practice of the psychiatrist

- 4 Social work knowledge-in-practice

- 5 Disability: a personal approach

- 6 Knowledge in the making: an analytical psychology perspective

- 7 Knowledge to action in the practice of nursing

- 8 The risky business of birth

- 9 Skills for person-centred care: health professionals supporting chronic condition prevention and self-management

- 10 Knowledge and reasoning in practice: an example from physiotherapy and occupational therapy

- 11 Using knowledge in the practice of dealing with addiction: an ideal worth aiming for

- Conclusions: Knowledge-in-practice in the caring professions: reflections on commonalities and differences

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Knowledge-in-Practice in the Caring Professions by Struan Jacobs, Heather D'Cruz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.