Shortly before taking up office as head of the British Government’s Central Policy Review Staff Victor Rothschild told a friend, ‘Until this week I never realised the country was run by two men whom I’d never heard of.’1 One was Sir Burke Trend, the Cabinet Secretary, of whom Henry Kissinger wrote: ‘he made the Cabinet ministers he served appear more competent than they could possibly be.’2 Trend himself was more prosaic: ‘Your concern is to see that issues are processed up properly and that they finally reach Cabinet – when they’ve got to go to Cabinet – in a sufficiently compact, intelligible, clear form for the Cabinet to know what it is they’ve got to decide; what are the pros and cons.3 This echoes Niccolò Machiavelli, in Sixteenth Century Florence who gave the governors of Florence ‘the information necessary to make appropriate and timely decisions’.4

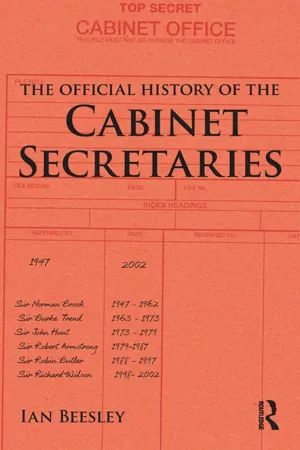

This account examines how six modern Cabinet Secretaries, who held office between 1947 and 2002, lived up to the challenge implied by Kissinger’s acclaim and pulls back a curtain of secrecy surrounding their activities. It is published as the office reaches its centenary. During that time there have been just 11 incumbents. The first, Maurice Hankey, held the position for 22 years, between 1916 and 1938. He was succeeded by Edward Bridges, the son of the Poet Laureate, who carried the position through the Second World War. Neither is discussed in detail in this volume. The former because there are already two significant studies;5 the latter because the requirements under Churchill during total war were exceptional. Nor are the three office holders after 2002 considered in detail, but for different reasons – notably the difficulty of achieving historical perspective at so short a distance.

Cabinet itself pre-dates the office of Cabinet Secretary. When George I came to the throne in 17146 it was a tradition that the Sovereign presided over a small selection of Privy Councillors assembled to give advice orally in his ‘cabinet.’ To protect the secrecy of that advice no unnecessary record of the discussions was made. However, King George did not speak English and ceased to attend the meetings, so that by the second half of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries a record of the discussions was taken and reported confidentially to the Sovereign.7 Yet in May 1839 minute taking fell into disrepair.8 Cabinet became an informal conversation between political allies, with no formal agenda and no record other than a private report from the Prime Minister to the Sovereign, of which there were only two copies. Cabinet Ministers raised issues orally, sometimes without warning, giving their colleagues scant opportunity to consult officials about the implications for departmental work. This had advantages – discussion was political not administrative and members of Cabinet were unlikely to have been captured by Departmental self-interest. On the other hand, Ministers sometimes left Cabinet meetings with differing views of what they believed had been agreed.9

The First World War

The First World War changed all that. It brought the mobilisation of national resources on a scale hitherto unknown and a new tautness in the administration of a five-man War Cabinet. In December 1916 David Lloyd-George,10 the newly chosen Prime Minister, brought in Colonel Maurice Hankey, who was the prewar Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence, to a new office as Secretary to the Cabinet. At 11.30 am on Saturday, 9 December 1916 the 39 year-old Hankey, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Dally Jones, sat down alongside the Prime Minister at the Cabinet table to record the decisions of the new Administration’s first War Cabinet.11 Lloyd George’s intention was that the record of War Cabinet decisions should be clear, so that the Departments knew what was expected of them. It was not his intention to give a verbatim account of the discussions and this has remained the case.12 Members of the Cabinet Office Secretariat record the logic of discussion, mainly without attribution, leading to an unambiguous agreement on action to follow, based on the Prime Minister’s summing up of the sense of the meeting. Formal votes are unusual and sometimes the Cabinet Secretariat (acting under the authority of the Cabinet Secretary) must extrapolate the decision that the Prime Minister would have recorded in a summing up – had there been one. Minute taking of this type is a skill of a high order. As Lord Radcliffe13 put it in a judgement about official secrecy, ‘Government is not to be conducted in the interests of history.’14

After the end of wartime conditions and the fall of Lloyd George in 1922 the arrangement barely survived an attempt by Bonar Law15 and Warren Fisher16 to incorporate the secretarial duties into the Treasury.17 The separate Cabinet Office Vote ceased; from 1923/4 provision for the ‘Offices of the Cabinet’ was carried on the Treasury Vote and by March 1923 staff numbers had been reduced from 123 a year earlier to 39. But Bonar Law fell ill and resigned on 20 May 1923 and that was as far as retrenchment went. His successor, Stanley Baldwin,18 did not have a secure political position and may well have been glad of the support of the Cabinet Office rump; and Ramsay MacDonald’s19 Administration of January 1924 had only four members with previous experience of office, so that they were more dependent on officials for the conduct of business than their predecessors. By the middle of the 1920s criticisms of the Cabinet Office had largely died away and procedures had been established that lasted up to the outbreak of the Second World War.

The Second World War

On 31 July 1938 Hankey retired, to be replaced by Edward Bridges from the Treasury who served until 1947 when he transferred back as Treasury Permanent Secretary20 – then the more senior of the two posts. His successor, Norman Brook, summarised Bridges’ contribution as, ‘Most people nowadays take the Cabinet Secretariat for granted – or, if they think about it at all, assume that it just sprang fully armed from the head of Hankey. In fact what Hankey created was the machinery – and very good machinery too, which has stood the test of time – but it was Bridges who breathed life into it and gave it flexibility and capacity for growth.’21

On the fall of Chamberlain on 10 May 1940 Churchill formed a War Cabinet of five members (later to become eight). He was both Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, with undefined powers that allowed him a personal, direct, ubiquitous and continuous control.22 This War Cabinet initially met every day at 11.30 am and sometimes also later during the day and evening – in all meeting 1226 times during the war in Europe.23 The process was far from smooth, however, with Ministers sometimes being kept waiting outside the Cabinet room for long periods or, if discussion took an unexpected turn, not being in attendance when issues of direct relevance to them were decided. So much time was spent in Cabinet that Churchill decreed that no ministerial boxes of papers requiring attention were to be sent to Ministers when they were in Cabinet except when unavoidable.24

On the home front the Lord President’s Committee, created in June 1940 under Sir John Anderson,25 progressively emerged as the principal organ dealing with social and economic matters. Thus, Bridges separated domestic policy from military issues, leaving the main task of liaison with the Chiefs of Staff to Hastings ‘Pug’ Ismay,26 (though Bridges was present at almost all meetings of the War Cabinet), and making good use on the civil side of things of his deputy Rupert Howorth,27 and later Norman Brook.28 SS Wilson’s history of the Cabinet Office records that ‘. . . in effect [Bridges] became Churchill’s chief civilian staff officer.’29

With Bridges’ support Churchill endeavoured to avoid large attendance at Cabinet Committees (when many of those present would not be directly involved) and by insisting that papers and the minutes of meetings should not be over elaborate.30 The minutes ceased to be circulated in draft – under wartime conditions, there was no time for the Prime Minister to review them and in any case he gave them scant importance, commenting to Bridges that, ‘I cannot allow Cabinet minutes to be sent out of the country, or made any use of. They are nothing more than your jottings down of lengthy conversations. No one who is really busily engaged in the war has time to read them, still less to correct them. I have repeatedly told you that your records are far too lengthy. In their present condition they are a most imperfect and misleading record.’31

Nevertheless, government largely remained a written culture until towards the end of the twentieth century and in this Churchill was no different. He complained that, ‘To do our work, we all have to read a mass of papers. Nearly all of them are far too long. This wastes time, while energy has to be spent in looking for the essential points.’32 Yet on 19 July 1940 he also sent Bridges and Ismay an instruction: ‘Let it be very clearly understood that all directives emanating from me are made in writing, or should be immediately afterwards confirmed in writing, and that I do not accept any responsibility for matters relating to national defence on which I am alleged to have given decisions unless they are recorded in writing.’33

We Won the War, How Do We Win the Peace?

At the end of 1944 Bridges described the functions of the Cabinet Secretariat prosaically as:

(a) Normal Secretarial duties – including follow-up action to make sure that decisions are carried out.

(b) The preparation of material affecting several Departments.

(c) Official correspondence with overseas authorities that is not the responsibility of any single Minister.

(d) Other – (1) urgent issues where the primary responsibility is not clear; (2) the organisation of Cabinet Committees; (3) as a temporary home for organisations not easily attached to some other Department; (4) certain international conferences and security issues – best treated as a personal arrangement for the Prime Minister.

Later, in evidence to the 1966 Fulton Committee inquiry into the civil service, he acknowledged that ‘my concern was not with policy, but to see that the general business of the War Cabinet ran smoothly.’34 His valedictory advice to Brook was: (1) That the Office continued to retain civil and military officers working alongside one another; (2) that administrative staff should be kept small in number; (3) that the Cabinet Secretariat should mainly be staffed by secondments of 2–4 years from Departments (to provide expertise and to emphasise that the Cabinet Office operated on behalf of the whole of government); (4) that the main duties of the Cabinet Office were seen as normal secretarial duties.35

Bridges and Brook faced the daunting task ...