eBook - ePub

Developing and Leading Emergence Teams

A new approach for identifying and resolving complex business problems

- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developing and Leading Emergence Teams

A new approach for identifying and resolving complex business problems

About this book

Developing and Leading Emergence Teams describes a future business landscape that seems to be complicated, complex and chaotic, in almost equal measures. The variety and diversity of the environments within which large organizations will be seeking to operate, require a similar variety of systems, process and structures if they are to respond successfully to emerging opportunities. The established models of teamworking (matrix, cross-functional or transdisciplinary) can all adapt to this new environment but will only do so if the culture, leadership and management style of the business enables this. The authors describe a model of emergence teams; high-trust teams that exhibit exceptional affinity for knowledge sharing, sense making, and consensus building. They then explore the specifics of leading such a team, how the team leader should: design the team; interact and facilitate the team's development; understand the personal nature of each of the team members and the overall emotional regime that will affect trust, commitment and motivation. Peter Smith and Tom Cockburn draw on research and detailed case examples to provide techniques your organization can adopt in order to build and support the various teams capable of addressing complexity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Developing and Leading Emergence Teams by Peter A.C. Smith,Tom Cockburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introducing the emergence team approach

The global business landscape has changed fundamentally and ‘normal’ is a thing of the past. This is the assertion made by Deloitte (2014) based on their research on global busin ess indices. They affirm that everyone is now working in the world of VUCA – an acronym used to stand for the volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity of general business conditions and situations. However, according to McKinsey & Company (2014) this new environment is ‘rich in possibilities for those who are prepared’. Our book ensures that its readers are indeed well prepared.

More specifically, our book is intended for senior executives and the emergence team sponsor(s) plus interested experienced practitioners, to provide them with an introduction to emergence teams including relevant significant background information, and specific guidance for ongoing emergence team activities. Secondly it is intended to assist the team leader in providing leadership for the emergence team and specific guidance in ongoing emergence team activities. Lastly, but very importantly, it provides practical knowledge and guidance with regard to team activities for the emergence team members.

Chapters 1 through 10 in this book are structured to provide a step-wise flow setting out:

- A general overview of the emergence team approach to significant, often complex, organizational problems; and describing a ‘base’ case study.

- The process of reaching consensus on the issues encountered by the team, including how to reach agreement on the context of the emergence team intervention plus a description of the sponsor’s role in the intervention.

- In what fashion the emergence team should be formed plus how the team leader, team members and interviewees should be chosen.

- Knowledge regarding the intervention that is vital for the team leader to possess and understand.

- Emergence team dynamics including theoretical fundamentals.

- Details of the skills and techniques that emergence team members must master.

- Details on embodying and embedding team intelligence-in-action.

- Digital technology options to facilitate emergence teamwork.

- The impact of future research on emergence teams.

- A revised case study of the case that was first sketched out in Chapter 1; this chapter indicates how that case would have been addressed using an emergence team approach.

Chapter 1 provides a foundation for appreciating why emergence teams hold the key to high performance in VUCA environments, and a framework for recognizing the value of later chapters. This book is a compilation of practical insights for readers to reflect upon and apply as appropriate; these insights are drawn from the authors’ extensive research and experience.

The Cynefin framework

Organizations typically try to apply simplified solutions to even the most urgent problems because they lack ‘situational awareness’. All too often they are trying to solve the wrong problem as they confuse symptoms and causes. This failure to attain expected results in spite of great effort is to a great extent attributable to the emergence of a new, unique class of problems for which conventional approaches and solutions are inadequate.

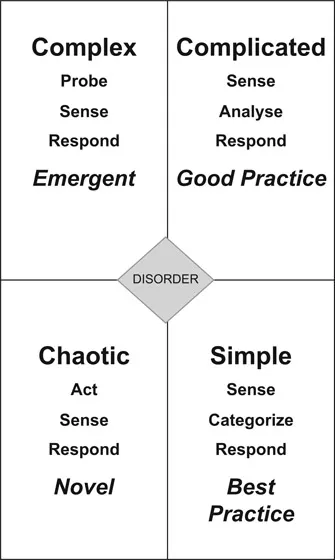

The nature of the issues facing leaders and practitioners as they grapple with the variety of problems they face is exemplified in Figure 1.1. This framework was developed by Dave Snowden (Snowden, 2014) to help define the kinds of actions that practitioners may gainfully apply in different business environments. It assists in determining the degree of business complexity in which practitioners are operating and the appropriate steps to take. As Figure 1.1 shows, each environment requires different actions. Snowden and Boone (2007) detail application of the framework and explain how informed decision makers tailor their approach to fit the environment they face.

Figure 1.1 Cynefin framework

Source: Adapted from Snowden, 2014

It should be no surprise to decision makers when previously successful problem solving approaches fail in new situations. Organizations typically try to apply simplified solutions to even the most urgent problems because they lack ‘situational awareness’. All too often they are trying to solve the wrong problem as they confuse symptoms and causes. The simple reason is that most organizations try to solve problems facing backwards! They confidently assert that what worked in the past will work in the future – try driving your car down a busy street that way. You’ll end up in the same ‘pickle’ as do such organizations – with a catastrophe! As Snowden and Boone (2007) assert: different contexts call for different kinds of responses. Before addressing a situation, leaders need to recognize which context governs it and tailor afresh their actions. To facilitate this, Snowden and Boone have formed a new perspective on decision making – the Cynefin framework – which they have based on complexity science. This framework assists leaders sort issues into five contexts as shown in Figure 1.1. The Cynefin framework may be interpreted and applied as described in the following paragraphs.

As Figure 1.1 indicates, simple contexts are characterized by stable cause-and-effect relationships that will be quickly evident to the majority of practitioners. In these stable contexts, decision makers must first ‘sense’ and affirm this context, then respond to it appropriately. Complicated contexts may contain multiple right answers, and though there is a clear relationship between cause and effect, not everyone can see it. Here, leaders must sense, analyse and respond. Senge (1990, p. 71) called this context ‘detailed complexity’ and likened it to mixing many ingredients in a stew or to a lengthy set of instructions for assembling a machine. The complex context is the realm of VUCA where correct answers cannot be inferred, and indeed, simply “searching for right answers is pointless” according to Snowden and Boone (2007, p. 5) since the results of a single intervention will not be obvious. However these authors claim that by first probing, then sensing, and then responding appropriately (doing no harm), instructive patterns will eventually emerge leading to problem resolution. In the complex context, caution must be exercised in regard to ‘quick fixes’ since problems may seem to be solved in the short term although even more serious problems may have been caused that may occur in the long term. Five approaches for managing in a complex context have been described by Snowden and Boone (2007, p. 6):

- ‘Open up the discussion, more interaction is required than in any other context

- Set barriers to delineate behavior

- Stimulate attractors – probes that resonate with people

- Encourage dissent and diversity

- Focus on creating an environment within which good things may emerge rather than trying to bring about predetermined results’

The chaotic realm is one of disorder, and exhibits dynamic shifting relationships between cause and effect that are impossible to determine, because they shift constantly and no manageable patterns exist. In this domain, the decision maker must first act to establish order, then sense where stability is present, and finally work to transform the situation from chaos to complexity.

The fifth context is disorder, and applies when it is unclear which of the other four contexts is predominant. The way out involves breaking the situation into its constituent parts and assigning each to one of the other four realms. Leaders can then make decisions and intervene in contextually appropriate ways. Extreme caution must be exercised in this context, since as Russell Ackoff (1977) warned 50 years ago, problems occur in systems which Ackoff termed ‘messes’; every time we try to solve one problem in isolation we simply create new problems that add to the mess.

Snowden and Boone (2007) describe the Cynefin framework as a tool for a leader to use in their decision making. Snowden (2010) describes the Cynefin framework as a ‘sense-making framework which is socially constructed from peoples’ experience of their past and also their anticipated futures … and is normally created as an emergent property of social interaction. One of the reasons for this is the need to root any sense-making model in peoples’ own understanding of their past and possible futures’. With this in mind, in our view, the use of the framework solely by leaders seriously short-changes its power, and in this book we recommend its use in team settings where conclusions drawn regarding environments and responses are emergent, enriched and reached by consensus based on organizational knowledge, team consensus or team input to the leader.

Cynefin is a Welsh word, which may be translated into English as ‘place’, although the term was chosen by Snowden (2014) to describe his understanding of the evolutionary nature of complex systems, and their inherent un certainty – the name Cynefin is his reminder that all human interactions are emergent and determined by experiences, both through the direct influence of personal experience, and through collective experience; for example through storytelling.

The four Cynefin environments and associated recommended responses are:

- Simple environment: sense–categorize–respond.

- Complicated environment: sense–analyse–respond.

- Complex environment: probe–sense–respond.

- Chaotic environment: act–sense–respond.

Many organizations categorize the environments they face without any examination as ‘known environments’, assuming, without further study, that the environments in question have been previously categorized. These organizations then respond by applying ‘best practices’; that is solutions that have worked in the past. However in our VUCA business world, where complex conditions exist in virtually all business situations, ‘Normal’ no longer applies and employing ‘best practices’ without very careful consideration does not take account of surprise factors and indeed often produces catastrophic results. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the average longevity of S&P 500 organizations declined from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today (Gittleson, 2014).

Application of Cynefin response #2 may seem to offer a safer, more general situational approach although ‘analysi s’ too has many pitfalls (Ackoff, 1981) and this environment would be better approached using systems theory (Ackoff, 1981). For example, analysis would not re solve the following question: why do two seemingly identical cars have the steering wheel on the left in one case and on the right in the other? A systems approach could tell us that one is built for the UK market and the other for the North American market.

Action learning

The experimental approach of ‘probe, sense and respond’ may seem to many practitioners unusual and overly cautious and demanding, although it is one that has served countless organizations well for many decades, for example, in complex plant optimization using statistical design and analysis, and also in organizational development where it is called ‘action learning’ (Revans, 1996). We recommend that the process of action learning be undertaken by an emergence team in sensemaking within the Cynefin framework as they explore the information generated from the interviews team members hold with organizational members. Some descriptive details of the action learning process are provided later in this chapter, and further practical details are provided in later chapters.

It is very important that the organization’s management and members of the emergence team understand the significance of learning for successful application of the Cynefin framework. Upon the detection of an error, most people look for ‘a quick fix’, that is another operational strategy that will work within the same goal-structure and rule-boundaries. This is ‘single-loop learning’ (Argyris, 1991) involving a simple feedback loop, where outcomes cause adjustment of behaviours, like a thermostat. This is generally the case when goals, beliefs, values, conceptual frameworks and strategies are taken for granted without critical reflection. A higher order of learning is realized when the emergence team, upon detecting a mismatch between the target organizational performance and reality, questions the goal-structures and rules that resulted in the performance realized; this is double-loop learning. It is critical to make sure that the emergence team’s action learning activity result in a ‘probe’ that will not produce disastrous results but rather provides the double-loop learning from which careful further probing may be planned after in-depth reflection via action learning (sensing, adapting). Although slow, this approach has no serious drawbacks, even when Cynefin environments #1 or #2 are actually being faced.

Action learning typically takes place among trusted colleagues in a group of about six people where the group (‘Set’) members encourage and help the group member(s) owning the problem to reflect on problem causes and possible courses of action before the Set member(s) with responsibility for the problem take(s) action. The action learning approach practised in organizations today has become highly structured and consultant/Set adviser-driven. For the generic purposes of this book we recommend the original approach pioneered by the founder of action learning in the 1940s – Professor Reg Revans (1996), or the well-respected variant introduced by Roger Gaunt (1991) which recognizes ‘emotion’ as a significant initiator of problems. Revans established action learning in very approachable terms in the 1940s, for example with groups of coal miners in the UK, based on the notion of an ad hoc group of colleagues sharing and reflecting on their practical experience and developing questions through which they might further learn and take reasoned action. The action learning cycle of taking action, reflecting on results and taking further action is repeated as necessary, forming the basis of an interactive step-wise adaptive (emergent) process comparable to the Cynefin process steps.

Smith (1997a) explains that, epistemologically, learning has typically been equated with the detection and correction of error and psychologists have traditionally associated learning with an invariant context (Weick, 1991). Since as explained above, rapid and large-scale contextual change may be considered the norm in today’s business, an invariant context does not exist, and trying to learn about the business environment by applying action learning may seem quite inappropriate. In contrast, the term adaption has typically been used by social scientists in situations where the context changes and the organization accordingly adapts itself or its environment (Ackoff and Emery, 1972). Revans (1982, 1984a) himself seems to have foreseen this confusion but chose simply to interpret ‘adapting’ as ‘learning’ since as he himself said, ‘Our ability to adapt to change with such readiness that we are seen to benefit may be defined as “learning”’. In this way he justified his using the term action learning, and we justify its use by emergence teams as described in this book.

It is clear that the Cynefin framework is intended as a means to ultimately take effective action, and in this regard Revans emphasized from the beginning that this was one of his principal intentions for action learning. For example, he wrote the following as a definition of action learning: ‘We are trying to encourage managers to discover how they can pose fresh questions in conditions of ignorance, risk and confusion; first to design a new course of action; second to implement the course of action’ (Revans, 1984a). Re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Introducing the emergence team approach

- 2 Team context definition and consensus building

- 3 Establishing an emergence team

- 4 Team leader insights

- 5 Emergence team dynamics

- 6 Team members’ insights

- 7 Team intelligence-in-action

- 8 Digital technology and emerging teams

- 9 Future research impact

- 10 Revised case study

- Acknowledgement

- Index