![]() PART I

PART I

Historicism and the Experience of History![]()

1

The Professor’s Dream: Architecture in Time

The Professor’s Dream, Cockerell’s best-known drawing (Plate 1), captures Cockerell’s fundamental views on architecture in time. It is a 6 ft wide by 5 ft high synopsis of architectural history, assembling over one hundred buildings from past to present times and layering them upon four terraces rather than along a single ground line. Each building is drawn at the same scale, with the entire composition rendered in watercolour. In 1849, the drawing was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and Cockerell sought to have a smaller version of it engraved. Destined though it was for exhibition, Cockerell’s drawing came after nearly a decade of teaching, and was undeniably imbued with pedagogical intentions.

The Professor’s Dream may also be Cockerell’s most widely reproduced drawing. Even those who know little about its creator will likely have encountered it, especially as the drawing has experienced a revival in the last decades. The ascent of postmodernism and that movement’s foundations in historicism inspired the use of The Professor’s Dream as a poster for the 1980 Venice Biennale.1 Over a decade later, the drawing featured on the cover of the book Architecture in the Age of Historicism. But was Cockerell’s ‘dream’ truly that of a historicist? The stylistic and temporal divisions within the drawing could lead to this interpretation. The temporal demarcation between the four horizontal layers, which designate stylistic breaks, could suggest a certain flattening of history. Yet the rich superimposition, the subtle perspectival effect, and the implied depth in the thickness of the paper intimate otherwise. If there is a parallel between nineteenth-century historicism and more recent postmodernism, the link between Cockerell’s drawing and the flattening of history is weak at best. Notwithstanding the apparent espousal of stylistic categorization, The Professor’s Dream implies a depth that challenges the premise of historicism. In this section we will consider the context within which the drawing was created to better comprehend some of the key aspects that characterized the professor’s conception of the relation between architecture and time. Looking at Cockerell’s drawing as a representation of architecture in history, we will cast it within a larger tradition of mapping not only architectural history, but also the history of the world and its geography.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY ‘MUSEUMS’ OF ARCHITECTURE

Bringing together numerous buildings from different times and places, Cockerell’s drawing belongs to a larger tradition of effectively creating museums of architecture by collecting examples from past and current practices and presenting them in different forms (models, fragments, measured drawings, or restorations).2 Ever since the eighteenth century, models and casts brought back from the Grand Tour had found their places in private galleries. Although some of these galleries were being quite easily transformed into public museums – notably, Sir John Soane’s gift of his house museum to the nation in 1834 marks the creation of the first public architectural museums in Britain – the history of the formation of the first museums of architecture is otherwise tumultuous.3 The difficult categorization of architecture as science or as art raised questions as to the epistemological limits and pedagogical uses of a museum of architecture. Describing the development of museums in eighteenth-century France, art historian Paula Young Lee discusses how the split between museums of art and museums of science was evident in the very naming of these places. The term ‘muséum’, a reference to the Musaeum of Alexandria, represented an idea about the production, accumulation and control of knowledge, and was used for museums of science. The term ‘musée’ was used for art museums, and linked back to a place dedicated to the Muses or more specifically to the Athenian hill, named after the poet Musée. While the former implied ‘means of knowing’, the latter was rather a ‘place of showing’, the difference expressive of a conflict ‘between doctrine and doubt, historical legacy and analytical evidence, conservation and progress [ … ]’.4 From D’Agincourt to Banister Fletcher (1866–1953), curators of architectural history inevitably positioned themselves between these conflicting poles.

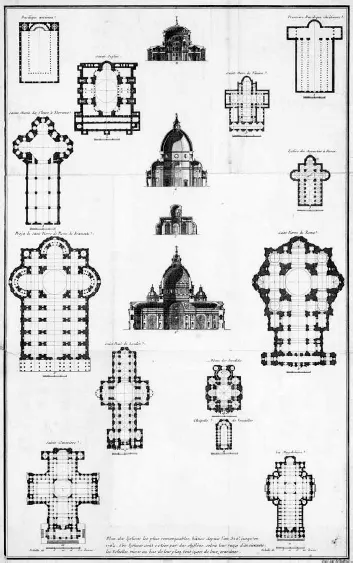

The Professor’s Dream takes place within a specific historiographical practice that we will refer to as the composition of a graphic museum. Whereas the recueil brought the buildings together within the space of a book, the graphic museum ordered history within one single frame. According to the architectural historian Werner Szambien, it is the use of this comparative technique that led to the production of such synopsis. Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68) was the first to apply the comparative technique to the study of architectural history, while the first graphic application of the technique is attributed to Jacques Tarade.5 In 1713, Tarade produced a number of drawings in which he compared St Peter’s Basilica in Rome with Notre-Dame de Paris and Strasbourg Cathedral, using half plans and sections.6 The limited scope of these first comparisons was greatly extended in 1762 with the publication of a survey of the ‘most considerable’ buildings from Egypt to the present drawn by architect Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695–1750).7 In his graphic museum, Meissonnier used a uniform scale and drew all buildings in elevation, grouping them in the abstract space of the white page. A year later, Julien-David Le Roy published a plate drawn by architect Jean-François de Neufforge (1714–91), which displayed the plans of the most remarkable churches built over the course of 2,000 years (Figure 1.1).8

1.1 J.-F. Neufforge, Plans des églises les plus remarquables, in D. Le Roy, Histoire des formes différentes que les Chrétiens ont données à leurs Temples depuis le Règne de Constantin le Grand, jusqu’à nous (Paris: Desaint & Saillant, 1764), Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture / Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Neufforge’s plate was the sole illustration in Le Roy’s publication on the history of Christian temples.9 Using different scales, Neufforge arranged the buildings chronologically down the page. Because the two plans drawn to the largest scale are the most recent ones, the impression is that the author advocates a progression of architecture from ancient to modern times. This contrasts with Meissonnier’s drawing, which instead reads as a random genealogy of form. Le Roy reaffirms his intention to present history as a progression with the publication of another plate six years later (Figure 1.2).

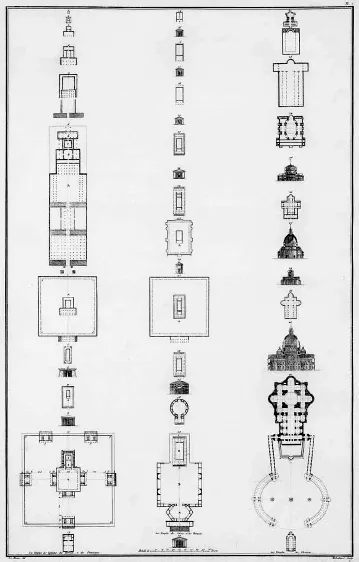

The plate that appeared in Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce is divided into three columns. The temples of the Egyptians, Hebrews, and Phoenicians are arranged down the first column, those of the Greeks and Romans in the centre, and the Christian Temples appear on the right. The buildings in the right-hand column, the majority of which already appeared in the 1764 plate, are now reduced to the same scale and aligned symmetrically about their centres. Compared to the first plate, it is evident in this second plate that Le Roy espouses a comparative technique as a system for classifying the past.10

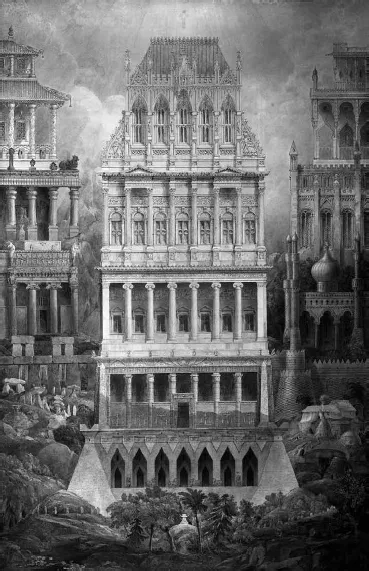

Many of these early French comparative drawings share the same characteristics: buildings are systematically selected, often symmetrically arranged, and then stretched as a series of line drawings on a white page so as to convey a sense of progress in time. The selected buildings suggest an all-inclusive approach, of all places and all times. The white background and the non-rendered plans, elevations or sections reflect the intended scientific objectivity. But across the Channel, another tradition existed. Unlike the French graphic parallèle, the English comparative drawings were rarely set in a neutral space. Almost always set within a larger atmospheric setting, the English drawings often presented their comparative studies as a great space to explore. In Comparative Characteristics of Thirteen Selected Styles of Architecture (Figure 1.3), English architect Joseph Michael Gandy approached the comparison of orders and the grouping of architecture from diverse origins in a manner very distinct from what has been described so far in the French tradition.11

At the centre of Gandy’s drawing rises a five-storey structure that leads from Babylonian pylons up to a Gothic roof, through Egyptian, Greek and Roman floors, as if the building was raised over 2,000 years. At either side of this central structure are two other tall buildings drawn in elevation, and which again display diverse architectures from remote times and regions shifting from floor to floor. A dramatic light hovers over a no less dramatic landscape in the background. Smaller primitive constructions – tumuli, tents, huts, and various druid monuments – are scattered in the foreground. While the layout suggests chronological progression and a potentially subtle judgment on the precedence of certain geographical origins, the emphasis is on the mythical, the symbolic, and the emblematic. The drawing’s content, composition, and treatment all contribute to convey a mystical quality rather than a sense of scientific objectivity. At the British Museum, James Stephanoff (1788–1874) presented a similar eclectic collection, a kind of anachronistic mosaic of different sculptures and paintings spanning nearly 2,000 years. Like Gandy’s comparative drawing, Stephanoff’s An Assemblage of Works of Art in Sculpture and Painting in the British Museum, From the Earliest Period to the Time of Phydias (Figure 1.4) hardly constitutes an objective chart.12 In both drawings, the sheer accumulation overshadows the potential rationalization.

1.2 D. Le Roy, Comparative table, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, considérées du côté de l’histoire et du côté de l’architecture, vol. 1 (Paris: De L’Imprimerie de Louis-François Delatour, 1770), Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture / Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

1.3 J.M. Gandy, Comparative Characteristics of Thirteen Selected Styles of Architecture. c.1826, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. By courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum

1.4 J. Stephanoff, The Ascent of the Arts: An Assemblage of Works of Art in Sculpture and Painting in the British Museum, From the Earliest Period to the Time of Phydias, 1845, British Museum, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

The drawings of English compatriots Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–52) and John Soane (1753–1837), and particularly their selections of scenes and buildings, suggest different motivations. Comparing medieval and modern scenes, Pugin uses the comparative technique to convey a certain atmospheric quality that privileges medieval morality. For example, he contrasts views of medieval London with nineteenth-century London, foregrounding a panoptical residence for the poor in the latter, and replacing the church spires that dominate the first image with smoke stacks. The cohesive religious community and the visible signs of spiritual guidance give way to the productive concerns of the larger industrial machine. In the case of architect John Soane, a most startling use of the comparative technique is evident in his drawing of a man-of-war against Noah’s Ark. Echoing the technique used by Tarade, Soane composed this image and a great number of other comparative illustrations by superimposing elevations and sections. The technique is similar to Tarade’s, but the overall effect could not be more different. Using dramatic contrasts in scale, Soane brings Rome’s St Peter’s and the Pantheon together with the Radcliffe Library in Oxford and Soane’s Rotunda at the Bank of England (Figure 1.5).

The sublime quality of Soane’s drawing contrasts sharply with the apparent scientific objectivity of Tarade’s comparative drawings. The intricate and dramatic spaces formed by Soane’s juxtaposition differ from the stark presentations of other French drawings such as those by Meissonnier or Neufforge. Unlike their French counterparts, the English comparative drawings are usually rendered and the represented buildings are situated in an impossible but imaginable place where there is both depth and light.

Cockerell’s Dream appears to straddle the French and English traditions: it is rendered yet ordered; it implies chronology even with its use of superimposition; it is comparative but also atmospheric. Upon its i...