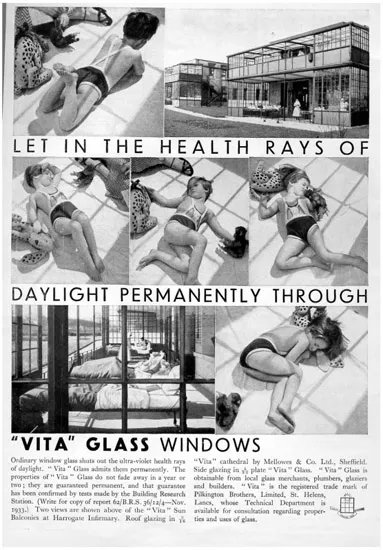

The new market created by the manufacture and marketing of the healthful ambience promised by Vitaglass had less in common with window glass than it did with a host of proprietary health products, such as vitamins or cod liver oil. Through its evocative visualising of the invisible properties of ultraviolet light, Vitaglass captured the imagination if not the market, and created an opportunity not only for competitors, but also for today’s tailoring of architectural glass to particular performance characteristics.

Light, Medicine, Health and Glass: From Finsen’s Light Cures to Lamplough’s “Vita” Glass

In the face of widespread death from infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza, the still mysterious debilitation of rickets and widespread urban pollution, health was a front-page issue in the 1920s and 1930s. Although in the period between 1850 and 1920 mortality from tuberculosis in England declined by two thirds and was continuing to fall, the disease continued to account for the overwhelming majority of deaths due to illness, and remained the leading cause of death among youths until the end of the Second World War.5 Thus, although mortality was declining in real numbers, infectious disease was a dominant concern for the popular media. Special interest groups, such as the New Health Society and the Sunlight League, further amplified this concern. The popular interest in health in England mirrored a longstanding worry with urban air quality that reached back to efforts to curb the burning of coal in London as early as the thirteenth century, and continued until the Great Smog of 1952.6

The connection between environment and disease, which had been the basis of urban sanitation movements, received increasing attention into the interwar years, particularly with respect to the sun. Following Dr. Niels Finsen’s triumphant treatment of tuberculosis with exposure to light, further successes in the treatment of tuberculosis and rickets with heliotherapy, such as Dr. Auguste Rollier’s alpine clinic or Dr. Henry Gauvain’s Alton hospital, positioned suntanning as a medical safeguard but also as a culturally desirable activity – a proxy indicator for a healthy body.7 On the one hand the biochemical and germicidal qualities of the ultraviolet spectrum of sunlight that underpinned heliotherapy fuelled an already established tendency to associate ill health with dirt and dust, and on the other hand they stimulated research and debate into how those qualities might be brought into atmospherically-polluted, sunlight-deprived cities, whether by bringing the country into the city, bringing the city into the country, remediating urban pollution, creating artificial sunlight through lighting technology, or enabling more sunlight to enter urban housing.8

The relation between light and health made an impact as changes in the economic climate and technological possibilities enabled transformations in the glassmaking industry, making the material more affordable and available in larger sizes to meet the demands of shifting sensibilities. Prior to the lifting of the glass excise tax in 1845, the dominant form of glass manufacture in England was the crown glass process, whereby spun discs of glass were then cut into squares.9 While it had exceptional brilliance, crown glass was limited by its optical quality and small sizes. Yet it continued to be produced, even as manufacturers were pressured by a demand for larger sizes due to the tax, which favoured the thinner crown glass over the more substantial plate and sheet glasses and gave it a cost advantage.10 The lifting of the excise tax and import duties in 1845 made the size and optical advantages of blown sheet more cost-effective, whether from British glassmakers or from continental competition, while the unit price of glass dropped by as much as 80%.11 Meanwhile, Britain’s Window Tax, first introduced as a wealth tax in 1696, was removed in 1851. In France the similar Door and Window Tax (contributions des portes et fenétres), introduced in 1798, was only rescinded in 1917.12 The burden of such taxes, which were levied at a rate per window, was particularly felt among the lower classes, who bricked windows up to lessen the tax burden. While the intent was that these taxes would be levied on property owners, in practice the effect was that in some cases the lower classes lived in rooms without any windows at all.13 By the times of their removal, both the Window Tax and the Door and Window Tax had long been widely condemned as taxes on light and air that were detrimental to the health of the population as a whole.14

As foundational as these developments were, the significant changes came with the arrival of automated glass production in the early twentieth century. Following John H. Lubbers’s (c.1852–1911) development of the automated cylinder process in 1903, the 1910s and 1920s brought mechanised drawn-sheet processes – implemented first by the Belgian Émile Fourcault (1862–1919) and the American Irving Colburn (1861–1917), followed by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company – which made sheets of increased size and optical properties possible. While different in their details, these processes were similar in their reconceptualisation of glass production. Preceding the techniques of blowing and flattening, both Fourcault and Colburn conceived of glass as being drawn in an infinitely long, flat ribbon, which could then be cut to length, cooled and polished. In addition to enabling glass sizes limited only by the practicalities of handling rather than by the limitations of blowing, the shifts from crown to sheet and from blown to drawn effectively moved glassmaking out of the domain of cottage artisans and into industrial production, such that by the early twentieth century glassmaking had become a large, internationally competitive business.

By the interwar years, glass had become the material of choice for architects seeking to both house and give expression to a new society. In response to the growing nineteenth century problems – new building types which reorganised urban space, new materials which displaced crafts with systems, a widening divide between rich and poor brought about by the reorganisation of both capital and society, and the industrial squalor of overcrowding, pollution and poor housing which resulted in the ill health of the population – architects looked to the very forces of industrialisation for possible solutions. In place of pollution, darkness, overcrowding and disease, they sought transparency, lightness, airiness, greenery and hygiene in projects and buildings at a variety of scales, from pavilions to entire cities. For their inspiration they looked back to the conservatory architecture of the nineteenth century, taking Joseph Paxton’s (1803–65) Crystal Palace from the Great Exhibition of 1851 as a model for a new architecture. The Crystal Palace was a feat of glass technology, utilising mouth-blown cylinder sheets in sizes that were larger than previously produced, and in a volume that was staggering for the mid-nineteenth century.15 The Crystal Palace was glazed with 300,000 panes of mouth-blown cylinder sheet glass provided by Chance Bros., each ten inches wide by forty-nine inches long, amounting to 900,000 square feet of glass.16 Considering the year the English excise tax was lifted was the year the Great Exhibition was conceived, and the year the Window Tax was lifted was the year the Exhibition opened, the Crystal Palace was as timely as it was revolutionary. The Crystal Palace’s lightness, transparency, systematic use of standardised components, functional approach in tune with biological imperatives and increased interface with the natural world found appeal among the architects of the early twentieth century, for whom it became a touchstone for a variety of overlapping sensibilities. In its slender and m...