eBook - ePub

Creating the Unequal City

The Exclusionary Consequences of Everyday Routines in Berlin

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creating the Unequal City

The Exclusionary Consequences of Everyday Routines in Berlin

About this book

Cities can be seen as geographical imaginaries: places have meanings attributed so that they are perceived, represented and interpreted in a particular way. We may therefore speak of cityness rather than 'the city': the city is always in the making. It cannot be grasped as a fixed structure in which people find their lives, and is never stable, through agents designing courses of interactions with geographical imaginations. This theoretical perspective on cities is currently reshaping the field of urban studies, requiring new forms of theory, comparisons and methods. Meanwhile, mainstream urban studies approaches neighbourhoods as fixed social-spatial units, producing effects on groups of residents. Yet they have not convincingly shown empirically that the neighbourhood is an entity generating effects, rather than being the statistical aggregate where effects can be measured. This book challenges this common understanding, and argues for an approach that sees neighbourhood effects as the outcome of processes of marginalisation and exclusion that find spatial expressions in the city elsewhere. It does so through a comparative study of an unusual kind: Sub-Saharan Africans, second generation Turkish and Lebanese girls, and alcohol and drug consumers, some of them homeless, arguably some of the most disadvantaged categories in the German capital, Berlin, in inner city neighbourhoods, and middle class families in owner-occupied housing. This book analyses urban inequalities through the lens of the city in the making, where neighbourhood comes to play a role, at some times, in some practices, and at some moments, but is not the point of departure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creating the Unequal City by Talja Blokland, Carlotta Giustozzi, Daniela Krüger, Hannah Schilling, Talja Blokland,Carlotta Giustozzi,Daniela Krüger,Hannah Schilling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Making the City Work: Practices of Segregation

Chapter 1

Spaces of Fear and their Exclusionary Consequences: Narratives and Everyday Routines of Sub-Saharan Immigrants in Berlin

Introduction

The Negro who ventures away from the mass of his people and their organized life finds himself alone, shunned and taunted, stared at and made uncomfortable … he remains far from friends and the concentrated social life of the church and feels in all its bitterness what it means to be a social outcast (Du Bois 1967 [1899], quoted in Sibley 1995, 146).

Racial segregation in cities has been an urban reality for centuries (Sibley 1995), and even today, Du Bois’s quote resembles the situation of Berlin. This chapter discusses racial segregation in Berlin today. It sketches the effects on segregation of those perceived as – and labelled by the middle class cosmopolites as – deviant, working class and Eastern German right-wing radicals for the capabilities of Sub-Saharan immigrants in creating a resourceful setting, while coping with a situation of marginalization. In short, subtle practices of the middle classes, as some of the upcoming chapters will show, marginalize immigrants. In their creation of durable engagements, middle class residents seclude themselves from others and produce spatial fringes in which urban cosmopolitanism is literally absent. While not demonstrably motivated by explicit racism, such practices are racist in their consequences. They sharply contrast with the picture commonly painted of cities like Berlin as cosmopolitan, a stage for open encounters between people of diverse backgrounds, especially in race and ethnicity. Marketing campaigns and tourist guides celebrate the city as the natural home of cosmopolitanism, although such campaigns champions only parts of the city. Other parts of the city, in contrast, show another social reality of right-wing violence that adds to the marginalization of non-White Germans and immigrants. As we will argue, an instrumental usage of the concept of cosmopolitanism serves expansionist economic politics of the neoliberal city (market cosmopolitanism) and deviates from actual practices of immigrant populations moving in European cities, like the creation of capabilities through moral orientations, durable engagements and fluid encounters (immigrant cosmopolitanism). Berlin reflects both these understandings of cosmopolitanism. This chapter discusses the role of market-oriented cosmopolitanism in creating spatial voids that marginalize people from places and resources in the city. How does it shape the creation of capabilities in the everyday life of Sub-Saharan immigrants? How is market-cosmopolitanism linked to the accessibility of the city for them?

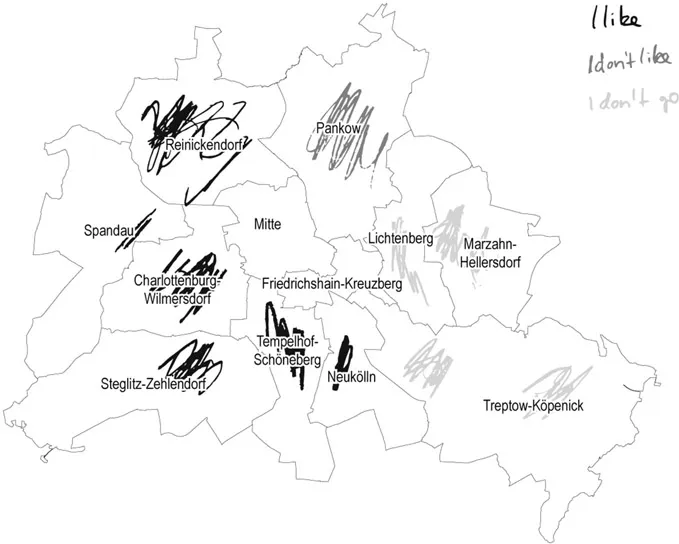

In semi-structured, in-depth interviews, we asked 40 Sub-Saharan immigrants, with at least five years of residence in Berlin, about their perception of the city and specifically of their neighbourhood, their access to the housing and job markets, their leisure time activities and personal ties. In this chapter, we focus primarily on questions about moving through the city, feeling safe or comfortable in certain areas. With a map of Berlin, the interview partners were asked to mark areas, which they ‘didn’t know’, ‘knew and liked’ and ‘knew and did not like’ (see Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2). Interview partners revealed a clear spatial pattern of city perception and city use: the avoidance of East Berlin.

First, we dismantle the discursive construction of Berlin as a cosmopolitan city. Second, we point to the voids and absent spaces in that image, namely the East Berlin region (see Figure 1.3). East Berlin became a commonplace for ‘spaces of fear’, which affected in particular the free movement of non-White Germans and immigrants. Third, the marginalized consequences of such places for this group of Berliners are then analysed through the lens of narratives and everyday routines of Sub-Saharan immigrants in Berlin.

As we have seen in the introduction, the capabilities of residents are framed by their structural positions and their spatial locations, and the ways in which their locations are produced by marginalization from other sites in the city. The unequal access of different social groups to the job and housing markets and other types of urban resources impacts people’s capabilities. We will see here how they are spatial. Next, we will see what alternative roads to resources those marginalized develop.

Cosmopolitanism and Geographical Imaginaries

Race and Space as Intertwined Constructs in the Cosmopolitan City

The increasingly popular term ‘cosmopolitanism’ wavers between political-philosophical ideas of world-citizenship, descriptive-analytical approaches to think beyond narrow national categories and empirical findings of ‘really existing cosmopolitanism’ as an unintended side effect of everyday life in a globally intertwined world (see Beck 2006, 17), turning it into the ‘cultural habitus of globalization’ (Ang 2001, quoted in Ley 2004, 159). City marketing campaigns in various cities promote cosmopolitanism to attract business, investors, international tourists, consumers and prosperous residents. As Young et al. (2006, 1688) argue, these campaigns create a ‘geography of difference’ through defining acceptable and unacceptable forms of difference in a hegemonic discourse about the ‘cosmopolitan city’. Marketing campaigns concentrate on certain areas, formulating their particular cosmopolitanism and the cosmopolitan lifestyle they offer and require. Following this, campaigns encode a specific vision of the cosmopolite who belongs in this cosmopolitan place (see Young et al. 2006, 1697).

Cities are presented to be the natural home of cosmopolitanism – and Berlin seems to be one of them. The official Berlin web page reveals its ambitions to become a leading international business site, drawing on its cosmopolitan character. The senate and business marketing departments sketch Berlin as an extraordinary business location, well situated in Germany and the European Union and therefore close to its important markets, offering a terrific inner city infrastructure, internationally connected, equipped with a highly qualified but reasonable work force, an international culture and a specific dynamism of innovation.1

In creating and promoting cosmopolitan identities for places and people who are meant to inhabit them, it becomes clear who and where these specific characteristics are missing. Non-cosmopolitan places and people are first of all defined by their absence (see ibid, 1702–3). The promoted market cosmopolitanism is expressed in a marketed lifestyle and in consumption practices requiring certain cultural and economic capital, which clearly excludes non-consumers and people missing valid cultural capital and/or economic means (see Kothari 2008, 500–501). This hierarchical and elitist understanding of cosmopolitanism simultaneously produces the non-cosmopolitan, for example the person lacking the correct type of difference: non-western immigrants and ethnic groups marked by skin colour and the respective prejudices, members of subcultures and the less wealthy (see Young et al. 2006, 1705–6; Ley 2004, 160).

Thus in the construction, perception and expression of a cosmopolitan identity (of the individual and the city) lies the imagination of the other, based on race, class and ethnicity (see Kothari 2008, 501). As David Harvey discusses in his essay on ‘Cosmopolitanism and the banality of geographical evils’ (2000), this applies to social groups and to place and space: ‘… the evil (if such it is) arises out of the dreadful cosmopolitan habit of demonizing spaces, places and whole populations as somehow “outside the project” (of market freedoms, the rule of law, of modernity, of a certain vision of democracy, of civilized values, of international socialism, or whatever)’ (ibid.,15). Especially the working class appears as the opposite to a cosmopolitan middle class (see Young et al. 2006, 1706). Working class neighbourhoods are therefore hardly considered as potential cosmopolitan places and usually are left out of respective image campaigns and urban politics. This is true for Berlin too, as Lanz (2007) shows in his analysis of the discursive construction of Berlin as an ‘occidental, multicultural and cosmopolitan immigrant city’. Political attempts to label Berlin as a multicultural and cosmopolitan world city were intertwined with discriminatory and racist discourses throughout the long immigration history of the city.

The traditional working class districts contribute to the ‘spatial construction of the other’ in the unified city (Lanz 2007, 146 ff.). Within this urban landscape of exclusion, boundaries between places and people labelled as cosmopolitan and non-cosmopolitan appear. Social categories of race and ethnicity are constructed to form visible subjects in specific space and time contexts (Keith 2005, 6–7 and 18–19). Hence forms and processes of racial discrimination, as exclusionary practices, become evident in a certain place at a specific time, using both geography and history as narrative structures to naturalize the reproduction of social inequalities (see Keith 2005, 18).

This was the case for so called ‘guest’ and ‘contract’ workers in Berlin. Here, the declining western districts Neukölln, Kreuzberg and Wedding had become immigrant quarters, populated by ‘guest workers’ families and following generations, which were never given a chance to escape their ‘migratory background’. Besides becoming the cities’ multicultural sites, as their culture was literally multi, they were stigmatized as ‘ghettos’ and even ‘parallel societies’, where ethnicity and cultural dispositions could be blamed for causing pressing social problems, decay, criminality etc., while deeper structures of inequality and racism were obscured (see Lanz 2007, 69 ff., 151–2, 157–8). In socialist East Berlin the relatively small numbers of foreign ‘contract workers’ were actively and officially segregated from locals and isolated in hostels in Marzahn, Hohenschönhausen and Lichtenberg, where then especially immigrants from the former Soviet Union settled after the fall of the Iron Curtain (ibid., 111 ff., 149). Together with Friedrichshain and Prenzlauer Berg (both branded as ‘bourgeois’ in built structures and therefore left to decay under communism), these neighbourhoods were mapped and labelled as places of social decline with high numbers of unemployment and welfare recipients (ibid., 149; cf. Holm 2006 on the development of the social composition in Prenzlauer Berg). Different to the western districts where immigrants had been present in larger numbers for some time already, another logic of externalization helped to exclude Eastern areas in public as the ‘racist other’.

Lanz presumed (2007, 132) that an increase in violence against foreigners and non-White Germans in East Berlin in the early 1990s could be influenced by a discriminatory discourse about asylum misuse and overwhelming foreign presence in the city and Germany as a whole. But rising numbers of racist attacks were explained by external conditions (crucial social changes in East Berlin) and the deviant behaviour of individuals. Instead of recognizing structural and institutional origins of racism in mainstream society, residents of East Berlin were discursively marginalized as ‘the other’ narrow-minded people with racist moral orientations, juxtaposed against the otherwise cosmopolitan population (ibid., 132 ff.).

In sum, two mechanisms of exclusion in the promotion of cosmopolitanism externalized certain areas and their inhabitants in a mutual way. First, in the discourse of the cosmopolitan, attractive city, non-cosmopolitan places and people were constructed and then excluded from image campaigns. But there is no empty space. So, second, precisely the excluded places were left to convert into ‘spaces of fear’, as we will see later, with the marginalized residents becoming potential suspects (neo-Nazis) or victims (non-White Germans and the visible immigrant population).

Besides image campaigns promoting Berlin’s cosmopolitanism, the existence of non-cosmopolitan places and people are not a secret to city officials. The report of the ‘Office for the Protection of the Constitution’ on political right-wing violence in Berlin identified ‘places of intensified right-wing violence’ in the Eastern districts Lichtenberg, Niederschöneweide, Prenzlauer Berg and Rudow in the west (see Verfassungsschutz Berlin 2007). These places of intensified right-wing violence are above-average scenes of crime and places of residence of the suspects. The report further reveals that the named districts are also places marked by right-wing extremism in a broader sense (measuring above-average votes for the right-wing extremist party NPD and density of places of residence, meeting points and activism of right-wing extremists). The time and sites of right-wing extremist violence reported by the Verfassungsschutz in 2007 coincide with the ‘spaces of fear’ later described by our interviewees and the points in time our interviewees see these spaces as being the most dangerous: during evening hours, at night and especially on weekends.

Although institutional and structural racism, the prevalence of right-wing extremist and racist opinions in mainstream German society, and related realities of everyday racism have been investigated and discussed in recent years (see Decker et al. 2012 and 2010; Stöss 2007; Terkessidis 2004), neo-Nazis are still regarded as a marginal problem located in the East of Germany and Berlin (see Stöss 2007, 49 ff.; Buchstein and Heinrich 2010, 34 ff.; Heinemann and Schubarth 1992) and externalized to certain social groups and areas (for a discussion see Bürk 2012, 27 ff. and 228 ff.; Döring 2008, 22–3; Terkessidis 2004, esp. 67 ff.). Market cosmopolitanism and its promotion support this process of spatial and social externalization of right-wing extremism and racism in the city of Berlin: marginalized as a deviance that is not its ‘true’ character. This not only allows for their violent manifestation in marginalized spaces (although not only there), the constructed non-cosmopolitan places and people also serve as a scapegoat and excuse not to face right-wing extremism and racism as a pressing problem in German society. Since Berlin is presented and perceived as open-minded, multicultural and cosmopolitan, racism must be denied as part of its city-culture. As Young at al. (2006, 1706) state, marketing campaigns only create the image of cosmopolitanism including certain places and urban dwellers and excluding others. Meanwhile the very residents of the cosmopolitan city articulate, live and fix the geography of difference in space. So the prevalence of right-wing extremism and racism performed by neo-Nazis in East Berlin, causes the avoidance of this part by their potential victims, as we will see below.

The Divided City

‘Spaces of Fear’: Narratives and Everyday Routines of Sub-Saharan Immigrants

Figure 1.1 Mental map by Sub-Saharan immigrants I

Source: © albertherrmann.de o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Creating the Unequal City

- PART I MAKING THE CITY WORK: PRACTICES OF SEGREGATION

- PART II MAKING THE CITY WORK: DEALING WITH MARGINALIZATION

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Index