eBook - ePub

Germans as Minorities during the First World War

A Global Comparative Perspective

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Offering a global comparative perspective on the relationship between German minorities and the majority populations amongst which they found themselves during the First World War, this collection addresses how 'public opinion' (the press, parliament and ordinary citizens) reacted towards Germans in their midst. The volume uses the experience of Germans to explore whether the War can be regarded as a turning point in the mistreatment of minorities, one that would lead to worse manifestations of racism, nationalism and xenophobia later in the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Germans as Minorities during the First World War by Panikos Panayi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Overview

Chapter 1

Germans as Minorities during the First World War: Global Comparative Perspectives

The First World War marked a major turning point in the relationship between minorities and majorities throughout the world, legitimizing persecution of those seen to have connections with the enemy, in particular. Although the rise of nationalism during the course of the nineteenth century had made those with the wrong ethnic credentials increasingly visible, the Great War would confirm new forms of persecution, which would reach their zenith in the Nazi empire of the Second World War.

On the one hand, we can therefore see the Great War as a major turning point in the history of minority persecution during the twentieth century. Those individuals associated with the enemy in particular had no place to hide as a combination of public opinion and government actions dehumanized, disenfranchised, physically attacked and expelled those populations which had any association with the enemy. While persecution during the Great War impacted upon a variety of groups in nation states throughout the globe, the minority which faced the most violent actions consisted of the Armenians in the dying Ottoman Empire, which most specialists on this subject describe as genocide.1 On the other hand, the most universally persecuted group consisted of Germans, who found themselves located in nation states which had declared war against their fatherland throughout the world from Brazil to the United States to most of Europe, and to those parts of Africa, Asia and Australasia controlled by the British and French empires.

While the German minorities of the First World War, unlike the Armenians, may not have experienced the type of mass killing which usually attracts the description of genocide, they certainly became victims of what would now merit the description of ethnic cleansing.2 As this essay and those which follow will demonstrate Germans faced a whole series of actions, which included restrictions upon movement, property confiscation, denaturalization, incarceration, violence and deportation. In fact, clear patterns emerge in the treatment of Germans during the Great War not just in terms of the restrictions and hostility which they faced but also in the timing of these developments, which seemed to occur at similar times on a global scale. While Germans represent one of many outsider groups to face exclusion and persecution during the Great War, the uniqueness of their experience lies in its global and simultaneous nature which someone of German birth or ancestry might face from Porto Alegre in Brazil to New York, through to London, Moscow and Wellington.

The German Diaspora on the Outbreak of Great War

A variety of reasons help to explain the persecution of Germans on a global scale. The first of these consists of the existence of a German diaspora both in myth and reality. The myth lies in the construction of a global Deutschtum as a result of the rise of German nationalism during the nineteenth century which viewed those of German origin who lived abroad as part of the Greater German Empire. While this idea partly emanated from Berlin and elsewhere in the German heartland, it also came from those living in locations throughout the world who perceived themselves as Germans either because they had recently migrated, or because their forefathers had maintained German identity over decades or centuries and had recently developed a new political consciousness with the rise of nationalism. The German diaspora in 1914 therefore needs analysis on the level of both myth and reality.

We can begin with the latter, where we first of all need to accept the fact that those considered as Germans lived all over the world due to previous migratory movements stretching back several centuries, which intensified during the nineteenth. The first emigration of Germans, who would evolve a distinct identity over hundreds of years, occurred into Eastern Europe. When the First World War broke out, most of these lived in the German or Habsburg empires and would only become minorities in the aftermath of the Great War in the newly created states which emerged from the breakup of these imperial entities, in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Hungary and Yugoslavia in particular. These groups would suffer an even worse fate than the Germans in the First World War as a result of their perceived role as Nazi collaborators.3 In 1914 the most visible German minority in Eastern Europe lived in Russia, which Dittmar Dahlmann, in his essay in the present volume, divides into four groups: the Volga Germans; the Black Sea Germans; the Baltic Germans; and the urban Germans in Russian cities, especially St Petersburg and Moscow. The first two groups were mainly agrarian and had moved to Russia from the 1760s following Catherine the Great’s Imperial Manifesto of 1762 and 1763, inviting foreigners to settle within the country to ‘furnish capital capacity, technical and other skills which the native Russian population was unable to provide’.4 About 27,000 Germans moved to the Volga, while 10,000 migrated to the Black Sea region.5 They could keep their religion, their language, schools and churches.6 The Baltic Germans, with origins in medieval migration, were mainly nobles or belonged to the upper strata of the towns as merchants or members of the professions. Many of them served the Russian state as officers or high-ranking officials.7 The Germans in Moscow and St Petersburg were initially merchants and subsequently industrialists or craftsmen, while some of them became teachers or professors at university. By the beginning of the twentieth century they had reached the third or fourth generation. Other Germans lived in the Caucasus region, in Southwest Siberia, in Volhynia and in some parts of Russian Poland. Although all the German colonists and the Baltic Germans were Russian subjects, many ‘urban Germans’ in St Petersburg, Moscow and Lodz were not, even if they were the third or fourth generation Germans.8

Most of the German minorities which existed as distinct ethnic groups in 1914, rather than in 1918, 1939 or 1945, therefore emerged as a result of emigration from Germany during the course of the eighteenth9 and, more especially, the nineteenth century when Germans formed an important element of the tens of millions of people who left Europe to settle in the Americas and beyond. Indeed, out of the 51.7 million people who left Europe between 1815 and 1930, 4.8 million were Germans.10 In recent years scholars such as Ulrike Kirchberger and Stefan Manz, working on the history of German settlement in Britain, have stressed the importance of network migration,11 which would also apply more generally to the migration movements out of the German Empire during the nineteenth century.12

But these communities emerged as part of a global migration process, which evolved during the course of the nineteenth century connected with the fundamental changes which affected the whole of Europe in this period. Such transformations would have had more of an impact upon the larger-scale German population movements which took place towards destinations beyond Europe, especially the Americas, than they would have done for the smaller scale networks, which moved towards European urban locations, such as, for example, Glasgow, as examined by Manz.13 The factors which underlay emigration from Germany during the course of the nineteenth century included rapid population increase caused by a combination of increasing fertility and decreasing mortality so that between 1816 and 1910 the population of Germany, defined by 1910 boundaries, had grown from 24,831,000 to 64,568,000. Against this we need to superimpose other underlying factors, such as patterns of land ownership and inheritance, which varied from equal bequest in the southwest from which much of the earlier nineteenth century migration occurred, to primogeniture in Prussia, from where emigration increasingly originated as the century progressed. In the former, increasing population meant that land parcels became too small to sustain a family while in the latter, the landless sons would have to move to urban areas in Germany or emigrate. Nineteenth century German out migration followed peaks and troughs, determined by economic crises in Germany, especially after the Napoleonic Wars, and the harvest failures leading to the 1848 revolutions, as well as by a spurt of United States industrialization between 1864 and 1873. A final important factor which increased nineteenth-century German emigration consisted of the development of the steam engine, which eased and speeded up journeys on a global scale.14

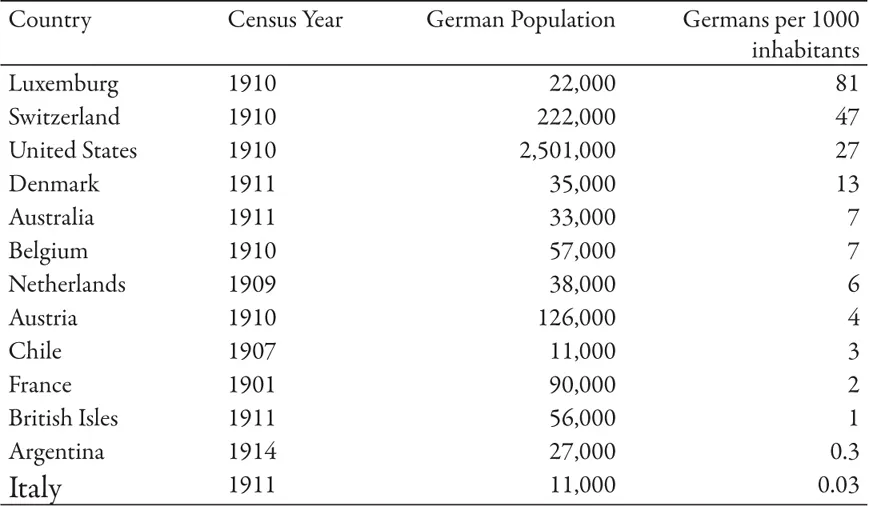

As a result of the processes outlined above, a global German diaspora had emerged by the outbreak of the First World War. Table 1.1 indicates the major foci of Germans by this time, according to one source from 1932. The table excludes one of the most significant German exile populations, in the form of those living in Brazil, which totalled approximately 400,000,15 as well as those in the Russian Empire. In addition, it does not include some of the small German communities, which had emerged as a result of colonial expansion.16

Table 1.1 Major German Populations at the Outbreak of the First World War

Source: F. Burgdorfer, ‘Migration across the Frontiers of Germany’, in Walter F. Wilcox (ed.), International Migrations (London, 1961 reprint).

As well as the reality of the presence of Germans throughout the world in the early twentieth century, a second verifiable fact consisted of the existence of German ethnic organizations. Although the article by Manz in the present volume stresses the role of concepts of global Deutschtum in the emergence of such groupings, many of them had more organic beginnings which those concerned with Germans abroad tried to unify as the First World War approached. As Stanley Nadel demonstrated in his study of New York during the middle of the nineteenth century, Germans shaped their ethnic identity ‘on an ad hoc basis, selecting from a broad range of developed options’, which included area of origin, class and religion.17 Similarly, Frederick C. Luebke has asserted that ‘few ethnic groups in America have been as varied in religious belief, political persuasion, socioeconomic status, occupation, culture, and social character as the Germans are’.18 The same author also points out that the Germans in the United States during the nineteenth century ‘identified themselves first of all as Catholics, Lutherans, Evangelicals, Mennonites, or Methodists, and only secondarily (sometimes incidentally), as Germans’.19 Similar assertions apply to German settlements throughout the globe. In Great Britain, for example, the Germans organized themselves in a variety of ways: politically, from anarchists and communists through to liberals, and pan-Germanists; religiously, they included Jews, Catholics, and Protestants. All manner of ethnic organizations emerged in Great Britain in the decades before the First World War, including churches, schools, political groupings and labour and professional bodies.20 In Russia, this took place on a much more significant scale because of the large numbers of people of Ge...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- PART I: OVERVIEW

- PART II: CASE STUDIES

- Select Bibliography of Key Works

- Index