![]()

Chapter 1

Educating "The Artist's Eye": Charlotte Brontë and the Pictorial Image

Christine Alexander

Jane Eyre is an amateur artist. She receives the conventional art education for young ladies at Lowood School and progresses to the stage where she can later instruct others and even reproduce a creditable likeness of the beautiful Rosamond Oliver. Her art becomes her mode of self-expression, revealing in rare glimpses her depth of character and aspirations for independence. Jane Eyre is Charlotte Brontë’s first novel in which the protagonist is a heroine and it is significant that her heroine should be a visual artist rather than a writer. Until the age of nineteen when she returned to Roe Head as a teacher, Charlotte intended to be a professional artist, but without the finances and necessary training she remained an amateur like her heroine. Much critical attention has been focused on Anne Brontë’s heroine as a professional artist in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, yet because Jane Eyre never sells her paintings her role as visual artist has been neglected. This essay attempts to trace Jane’s experience of art as a representation of Charlotte Brontë’s own education and artistic trajectory, and by extension that of all young women of the period whose lives were circumscribed by convention. In the process, the essay will provide a survey of the type of visual art that influenced the Brontë family in their formative years.

The critic George Henry Lewes noted in his 1847 review of Jane Eyre: An Autobiography: “It is an autobiography,—not, perhaps, in the naked facts and circumstances, but in the actual suffering and experience.”1 The obvious claim to realism in the subtitle of the novel has tended paradoxically to deflect our attention from what seems to be Lewes’s rather obvious comment: the subtitle self-consciously reinforces (by appearing to deny) the novel’s status as novel, a fictional claim to realism that foregrounds the novel’s own artifice and intentionally diminishes our response to Jane Eyre as “the actual suffering and experience” of the author.2 As the subtitle ambiguously suggests, then, Jane Eyre represents the author’s own spiritual growth to maturity, not least her experience as an amateur artist. Fictional autobiography as it is, the novel is infused with Charlotte’s personality and reflects her attitude to her early education in a conventional nineteenth-century visual culture. Thus Jane Eyre’s story is grounded in a discourse of Victorian accomplishment in the visual arts.

Nineteenth-century art manuals and essays stressed the importance of prints and drawings in educating the eye of young aspiring artists. John Burnet’s Essay on the Education of the Eye with reference to Painting (1880) notes that “[v]isual impressions are those which in infancy furnish the principal means of developing the powers of the understanding; … and it is also from the same inexhaustible fountain that the poet draws his most pleasing and graphic as well as his sublimest imagery.”3 Like the young Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë habitually retreated to a secluded place to examine a book—“taking care that it should be one stored with pictures”;4 and as Burnet suggests, the later writer resorts to pictorial images she had studied in detail as a child: the vignettes in Bewick’s History of British Birds, the picturesque plates in the art manuals and Annuals, the ideal portraits in albums of “Byron Beauties,” or the sublime scenes in John Martin’s engravings that hung on the Haworth Parsonage walls and were described in the pages of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

Very few of the Brontës’ own books with engravings survive. Only a natural history book, a drawing manual of trees, and A Description of London (1824) indicate the types of “adult” picture books the family owned;5 and the various marginal notes and sketches indicate that they were well used by the children. It is clear from their writing and illustrations, however, that they also owned a number of other illustrated books, in particular Bewick’s History of British Birds and at least three of the popular lavishly engraved Annuals. The Brontë juvenilia indicate that the children had early access to the works of Scott and Byron, to a number of plays by Shakespeare, to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, the exotic fantasies of the Arabian Nights, and James Ridley’s Tales of the Genii. Like Jane Eyre, Charlotte at an early age had read Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels with “its marvellous pictures” (JE 20) and Johnson’s Rasselas, on which she based her own tale “The Search after Happiness.”6 As a child, she had read “by stealth with the most exquisite pleasure”7 early issues of her mother’s illustrated Lady’s Magazine, published monthly (1770–1848) to entertain and educate a female audience through poetry and serialized fiction. Charlotte’s letters show that by the age of sixteen she had read histories by Hume and Rollin, the poetry of Milton, Shakespeare, Thomson, Goldsmith, Pope, Scott, Byron, Campbell, Wordsworth and Southey, biographies such as Boswell’s Life of Johnson, Southey’s Life of Nelson, Lockhart’s Life of Burns, Moore’s Life of Byron, and natural history by Audubon, Goldsmith, and White.8 Many of these books contained pictures that became the sources of Brontë drawings or were imaginatively translated into their writings.

The profound effect that Bewick’s two-volume History of British Birds, in particular, had on the creative development of the Brontës cannot be overestimated. Judging from their surviving illustrations, Mr. Brontë’s 1816 edition of British Birds was their earliest copybook, and the legacy of Bewick’s ability to elicit an emotional and imaginative response is evident in their writings. Charlotte wrote of Bewick’s “enchanted page/ Where pictured thoughts that breathe and speak and burn/ Still please alike our youth and riper age.”9 She realized that he had the ability to infuse deep feeling into both his verbal and visual text, while remaining “[t]rue to the common Nature that we see.” This is the “quiet poetry” that Branwell Brontë so admired and likened to the realistic truth of Hogarth’s engravings in his article “Thomas Bewick” published in the Halifax Guardian (1 October 1842).10

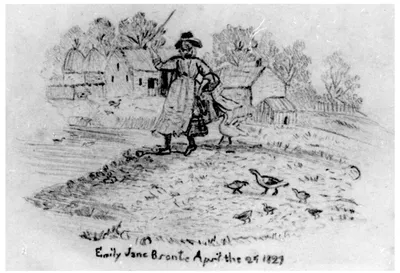

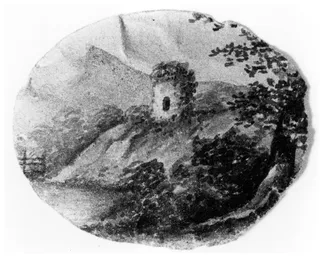

Bewick’s superior technique of using the end grain of hard wood had revived the art of wood engraving, and his books were popular, affordable and enthusiastically recommended by Blackwood’s, the Brontës’ favorite periodical. Mr. Brontë had a particular fondness for this north-country artist, with his keen observation of nature and everyday life. Any hero endorsed by “Papa” was immediately adopted by his children, although it is clear from their early and enduring response to Bewick’s lively engravings that they needed little encouragement. They used Bewick’s woodcuts as models in their earliest drawing lessons (Figure 1.1). Between 1828 and 1833, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne made six copies of Bewick’s miniature wood engravings from volume 1, Containing the History and Description of Land Birds; and five more copies from volume 2, Containing the History and Description of Water Birds, the volume that so impressed Jane Eyre. They are also likely to have made many more copies now lost. Other drawings exist that, while not exact copies, indicate the formative influence of Bewick on the siblings’ imaginations, such as the five miniature oval vignettes by Charlotte that came to light only in 2004, after the publication of The Art of the Brontës.11 These chiefly depict romantic scenes: three pencil sketches of cottages, an ink wash landscape with a ruined castle (an image that is not unlike those of Gilpin in Three Essays;12 see Figure 1.2), and an ink sketch of a lady addressing a parrot. Even Charlotte’s earliest story, written for her youngest sister “Ane” in a miniature hand-sewn booklet, is interspersed with tiny Bewick-like illustrations.13 Here the pictures are integral to the text, like Bewick’s large ornithological plates showing each bird in its habitat.

Fig. 1.1 “The farmer’s wife,” pencil copy by the ten-year-old Emily Brontë from one of Thomas Bewick’s “tail-pieces” in A History of British Birds, vol. 2.

Fig. 1.2 Miniature vignette, ink wash by Charlotte Brontë, c. 1829.

But the woodcuts that most appealed to the young Brontës, as they did to Jane Eyre, were the oval vignettes or “tail-pieces” at the end of each section, often unrelated to the text but depicting a typical country scene or making a wry, even coarse, comment on life: urchins chasing a dog with a tin can tied to its tail, a traveler urinating against a wall, a “black, horned thing” (JE 5) sporting behind a rock while a crowd watches a man hanged on the gallows, or a small boy leading a blind beggar across a stream—both oblivious of the warning on the signpost behind them. The grim humor and the small size of these vignettes would have appealed to the creators of the miniature magazines of the Glass Town saga. For all the Brontës, as for Jane Eyre, “[e]ach picture told a story” (JE 5), a narrative that imparted information as it stimulated the imagination.

The Brontës were well aware that engravings and woodcuts played a major role in the dissemination of ideas and information, and that appreciation of the aesthetic value of prints accompanied the recognition of their social and political significance. Prints provided the only visual commentary on contemporary events and reflected the morals, manners, and popular aesthetic values of the time. The conscientious young Charlotte was keen to improve her mind and to learn new skills. A school friend reported that she “picked up every scrap of information concerning painting, sculpture, poetry, music, etc. as if it were gold.”14 Contemporary art manuals directed students to study and imitate the masters, so at thirteen Charlotte compiled a “List of painters whose works I wish to see” that included “Guido Reni, Giulio Romano, Titian, Raphael, Michelangelo, Correggio, Annibale Carracci, Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Bartolommeo, Carlo Cignani, van Dyck, Rubens, Bartolommeo Ramenghi”15— a formidable list for a girl of her age. She would have read about such artists in Blackwood’s and Fraser’s, and seen engravings of their works in drawing manuals and at the home of her friend Mary Taylor, whose father—the original of Hiram Yorke in Shirley—was a keen collector of paintings and engravings. Raphael’s cartoons in particular were popular as plates for young ladies to copy. Charlotte’s large copy of the central heads in Raphael’s “Madonna of the Fish” and her two highly accomplished classical heads,16 made at the same time, suggest she was working from one of these manuals. Mary Taylor, too, made a watercolor copy of Raphael’s “Madonna della Sedia” several years earlier.17

Print collecting became the hobby not only of the connoisseur but also of the accomplished young lady, keen to compile a repository of pictures to copy. Inn...