- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The amusement parks which first appeared in England at the turn of the twentieth century represent a startlingly novel and complex phenomenon, combining fantasy architecture, new technology, ersatz danger, spectacle and consumption in a new mass experience. Though drawing on a diverse range of existing leisure practices, the particular entertainment formula they offered marked a radical departure in terms of visual, experiential and cultural meanings. The huge, socially mixed crowds that flocked to the new parks did so purely in the pursuit of pleasure, which the amusement parks commodified in exhilarating new guises. Between 1906 and 1939, nearly 40 major amusement parks operated across Britain. By the outbreak of the Second World War, millions of people visited these sites each year. The amusement park had become a defining element in the architectural psychological pleasurescape of Britain. This book considers the relationship between popular modernity, pleasure and the amusement park landscape in Britain from 1900-1939. It argues that the amusement parks were understood as a new and distinct expression of modern times which redefined the concept of public pleasure for mass audiences. Focusing on three sites - Blackpool Pleasure Beach, Dreamland in Margate and Southend's Kursaal - the book contextualises their development with references to the wider amusement park world. The meanings of these sites are explored through a detailed examination of the spatial and architectural form taken by rides and other buildings. The rollercoaster - a defining symbol of the amusement park - is given particular focus, as is the extent to which discourses of class, gender and national identity were expressed through the design of these parks.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Architecture of Pleasure by Josephine Kane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Fortune in a Thrill: The Rise of the Amusement Park, 1900–1920

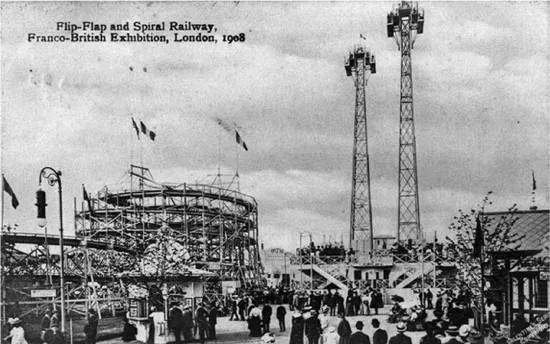

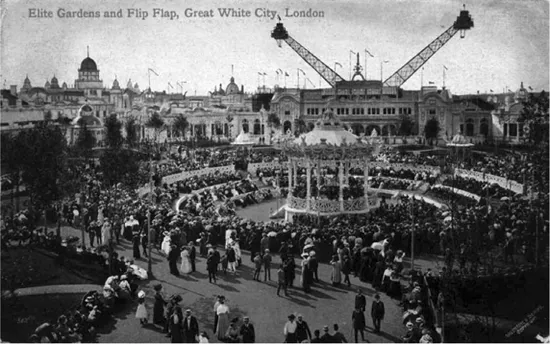

In April 1908, the World’s Fair published an account of the progress of the new White City exhibition ground at London’s Shepherd’s Bush. Under the creative control of Imre Kiralfy – famed for his spectacular theatrical productions on both sides of the Atlantic – a series of grand pavilions and landscaped grounds were underway, complete with what would become London’s first purpose-built amusement park.1 The amusements at White City had been conceived as a light-hearted sideline for visitors to the inaugural Franco-British Exhibition, but proved to be just as popular as the main exhibits. Its spectacular rides towered over the whole site and were reproduced in countless postcards and souvenirs. Descriptions of the ‘mechanical marvels’ at the amusement park dominated coverage of the White City in the national press. Readers of The Times were informed of long queues of visitors waiting for a turn on the Flip Flap – whose gigantic steel arms carried passengers back and forth in a 200 foot arch – and of the endless line of cars crawling to the top of the Spiral Railway before ‘roaring and rattling, round and round to the bottom’.2 The Franco-British Exhibition was visited by eight million people, but it was the amusement park which captured the public imagination and made a lasting impression.3

1.1 Flip Flap and Spiral Railway, White City, London 1908.

1.2 Elite Gardens, White City, London 1908. Kiralfy’s architectural vision drew heavily on the design of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition 1893. The twin arms of the Flip Flap – which arced back and forth continuously each day – dominated the entire exhibition grounds.

The following year, in a survey of London exhibitions, The Times acknowledged the growing importance of amusement areas, observing that ‘we can no longer romanticize collections, however vast, of the industries of all nations. We do not go to exhibitions for instruction […] the great mass of people go to them for pure amusement’.4 The universal appeal of these amusement zones was deemed particularly noteworthy, and a remarkable royal endorsement just two months later provided definitive proof that the amusement park was not just for the masses.

In July 1909, Queen Alexandra and Princess Victoria, visiting the Imperial International Exhibition at the White City, were given a tour of the amusement park and – much to the delight of the crowds – decided to sample some of the rides. The London Daily Telegraph reported that the Princess rode the Witching Waves (an early incarnation of the dodgems, recently imported from America, see Figure 2.8), while the Queen herself took a trip on the Scenic Railway rollercoaster (Figure 3.1) and completed two winning runs on the Miniature Brooklands racetrack.5 It was a promotional masterstroke, signalling to the country that mechanised amusement had joined the ranks of respectable entertainments. Just as Queen Victoria’s attendance at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show at Earl’s Court in 1887 ensured massive and lasting success for similar re-enactments,6 amusement parks across the country reaped the benefits of the Royal visit.

In 1909, the amusement park phenomenon was still a novelty in Britain. But the opening of London’s White City coincided with a frenzied phase of investment in American-style amusement parks across the country, which – though short-lived – had a lasting impact on British popular entertainment. This chapter traces the rise of the very first amusement parks in Britain, following the fortunes of Blackpool’s Pleasure Beach and its south coast competitors, and the ambitious entrepreneurs who created them. It begins with an outline of the social and economic conditions which helped forge a new mass audience for commercial entertainments in Britain, and the key role of American amusement parks in providing initial inspiration.

PRECURSORS AND PIONEERS

The speed with which amusement parks sprang up across Britain in the first years of the twentieth century was largely thanks to the sociocultural conditions in Britain at the time, which were ripe for new commercial entertainment ventures. Economically, the years between 1870 and the First World War were buoyant. While manufacturing remained at the core of Britain’s economy, a shift away from agriculture towards the service sector was reflected in the dramatic growth of urban areas and the expansion of the white collar lower middle-class. Urbanisation and an upward trend in real wages combined to produce an estimated increase in per capita consumption of 33 per cent between 1870 and 1913. But, while standards of living improved for some sections of the working classes, nearly a third of the population lived at least some of their lives on the margin of subsistence.7

The changes wrought by the industrial revolution had, by 1900, transformed leisure practices. Industrialised working conditions and regularised hours, created clearer boundaries between work and non-work activities for the masses. The security of regular salaries and increased female employment bolstered the average household income, and facilitated spending on recreation. From the 1880s a world of commercially produced leisure, operating outside working hours in dedicated urban places, was rapidly gaining momentum. Investors seized the opportunity to develop large-scale entertainment facilities, catering for the newly enfranchised leisure classes with a wide spectrum of commercial recreations, from the ‘improving’ and ‘healthy’ to the more morally dubious. Music and dance halls, museums and art galleries, annual fairgrounds and exhibitions, and a variety of spectator sports – notably football – flourished across the country. As railway travel became affordable and accessible, seaside resorts became the focus of mass holidays and excursions, and increasingly catered for popular tastes. From the 1860s, coastal resorts such as Brighton, Margate and Blackpool replicated and relocated successful urban recreations in the form of piers, winter gardens, variety palaces, and sports grounds. Once élite resorts increasingly offered affordable and familiar entertainments with a veneer of luxury and exoticism, thereby preserving a profitable air of social aspiration.8

These developments amounted to a significant democratisation of leisure practices. The experience of leisure in its broadest sense had become, by the 1890s, a form of conspicuous consumption for all but the very poorest individuals. Scholarly work on the history of leisure is dominated by the theme of class identity and social control. Central to these themes is the argument that economic growth and social tensions resulted in the substitution of traditional recreations for a commercialised, sanitised leisure industry, well-equipped to channel nationalist, jingoistic and socially conservative discourses.

Yet, alternative readings suggest a more complex picture, revealing the mass audience as being far from passive, and differentiated by multiple variables, including age, gender and locality.9 Amusement parks catered for this newly enfranchised heterogeneous leisure class whilst taking advantage of the growth and diversification of urban entertainments, the rise of the seaside as a form of popular recreation, and a widespread fascination with American popular culture.

Spectacular Entertainment and a Taste for Novelty

The earliest amusement parks drew on a rich culture of commercial entertainment operating in Britain by the turn of the twentieth century – a culture which reflected the tastes of an emerging mass market and an enterprising group of businessmen. Coney Island provided the initial inspiration for the first parks, but their success rested on a skilful appropriation of long-established entertainment traditions. In particular, it was the fairs, circuses and music halls which primed audiences for the commodified pleasures of spectacle, excitement and mirth which formed a core element in the amusement park formula. Amusement park promoters who, on the one hand, touted the uniqueness of their new ventures were, on the other, carefully selecting the most successful elements of well-known diversions. Alongside the novelty of huge speeding mechanical rides, amusement park visitors were faced with an array of familiar attractions. These included sideshows and small-scale rides imported straight from the travelling fairgrounds; freak shows, acrobatics, clowns, and performing animals appropriated from the circus; and the novelty acts – such as the cinematograph – which characterised the ‘up-to-dateness’ of Music Hall programmes. The amusement parks relocated these elements to a permanent, landscaped, outdoor recreational space. Many incorporated gardens and quiet retreats, providing an escape from the noise and crowds, mirroring the role of public parks and pleasure grounds in Victorian cities.10

It was the environment in which these attractions were presented, however, that marked out the amusement park as a new kind of outdoor entertainment space, and here the influence of international exhibitions and emerging department stores becomes important. These defining forces in late Victorian British culture mixed people, commodities and visual spectacle on a scale hitherto unimaginable. Huge crowds who paid to gaze in awe at the latest wonder – a revolutionary agricultural device at Olympia or a dazzling display of haberdashery at Harrod’s – became a defining characteristic of late...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 A Fortune in a Thrill: The Rise of the Amusement Park, 1900–1920

- 2 A Whirl of Wonders! Technology, Machine Bodies and Moving Images

- 3 A Great Fun City: Crowds, Space and Time

- 4 Putting Order into Chaos: The Amusement Park, 1920–1939

- 5 Shifting Modernities: Pleasure and Leisure at the Amusement Park

- Conclusion: Modern Pleasures

- Bibliography

- Index