eBook - ePub

Ceremonial Entries in Early Modern Europe

The Iconography of Power

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ceremonial Entries in Early Modern Europe

The Iconography of Power

About this book

The fourteen essays that comprise this volume concentrate on festival iconography, the visual and written languages, including ephemeral and permanent structures, costume, dramatic performance, inscriptions and published festival books that 'voiced' the social, political and cultural messages incorporated in processional entries in the countries of early modern Europe. The volume also includes a transcript of the newly-discovered Register of Lionardo di Zanobi Bartholini, a Florentine merchant, which sets out in detail the expenses for each worker for the possesso (or Entry) of Pope Leo X to Rome in April 1513.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ceremonial Entries in Early Modern Europe by J.R. Mulryne,Maria Ines Aliverti,Anna Maria Testaverde in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Storia dell'arte rinascimentale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Theme of War in French Renaissance Entries

At first sight, one might not associate French royal entries with the theme of War. The tradition inherited from the Middle Ages of joyeuses entrées, made early in each new reign, performs the functions of confirming civic privileges and showing off the new monarch to his subjects. A variation of this tradition was seen in 1530–1533, when the new queen, Eleanor of Austria, and the royal children, previously held as hostages, were paraded throughout the kingdom on their return from Madrid following peace with Spain. The joyeuse entrée fitted neatly into the habits of an itinerant court, where there was less of a rôle for the king as Warrior than as good governor who brings Peace and Ubertas (fruitfulness, prosperity). The cities responded with expressions of devotion in a procession of the clergy, the university, the parlement, the merchants, guilds and corporations. Such military element as there might be consists in this parade functioning as a review of the local militia, which the guilds and corporations provided in time of war.

But special circumstances in sixteenth-century France bring the theme of War into the foreground. A whole propaganda of conquest grew up from the late fifteenth century, associated with the Italian campaigns of Charles VIII and Louis XII. When Charles VIII entered Vienne in 1490, the account of the entry contains a poem wishing him to be as victorious as Hercules, Charlemagne, Roland, Dunois.1 Four accounts survive (one printed) of the entry of Louis XII to Rouen in 1508, in which the second mystère (pageant) along the route shows a porcupine fighting a three-headed monster representing Genoa, Milan and Rome.2 Manuscripts of the poems recording Louis’s campaigns against Genoa and Milan3 display a series of miniatures of the campaign by Jean Bourdichon, two showing Louis setting out for war,4 one showing the artillery,5 one an initial French defeat,6 another the storming of a fortress,7 the submission of its inhabitants8 and the triumphal entry of the victor to Genoa.9

This theme was sustained under the reign of François Ier with his campaign in Northern Italy, in which he waged war to reconquer the duchy of Milan, claimed as his by dynastic right through his mother Louise de Savoie. The manuscript album of his entry to Lyon (now in Wolfenbüttel) portrays the king as a stag, ‘alant à son entreprinse et conqueste de sa duché de Milan, usurpée par Souysses et Alemans, sans aucun tiltre de droict’ (‘going on his campaign to conquer his duchy of Milan, usurped by the Swiss and Germans without any right’).10 One miniature shows the Connétable de Bourbon holding a flaming sword to clear a passage for the king,11 and is followed by a speech of Amour royale against Ludovico Sforza, il Moro, who has usurped Milan,12 and who, in the guise of the Bear, is portrayed as the only menace to the Parc de France, which has driven out other invaders, and is at peace but for this threat.13 A further text and miniature shows the Jardin de Milan, in which the king, this time in the guise of ‘le Noble-Champion, Hercule, délivrant les Hesperides et cueillant les pommes d’or’ (‘the noble champion, Hercules, freeing the Hesperides and plucking the golden apples’), is shown liberating his reconquered duchy.14 The victory at Marignan was to be celebrated in later royal propaganda, notably in the drawings (c. 1562) by Antoine Caron for the Valois tapestries, showing this victory15 or the submission of Milan.16 The same tapestries mythologise François as the warrior king, showing the education of a king for war,17 or François leading a triumphal march against the army of Charles V, or capturing a fort.18

Under the reign of his son, Henri II, the joyeuses entrées were given a strongly military stamp. Entering Lyon in September 1548, the new king had just been visiting his conquered territories in Piedmont, and was led through a series of triumphal arches and past other monuments dedicated to War, to Bellona and Mars. On two sides of the obelisk, not illustrated in Salomon’s woodcut, there were compartments portraying Victories, and beneath them figures of what Scève describes as Discords or Furies, who were blowing on fires in classical vases: in Colonna, the vase with flames is an attribute of Discord. The pedestal of the obelisk is shown in the woodcut to have been painted with an imitation of a Roman relief showing a battle with cavalry, reinforcing the association of the king with Victory.19

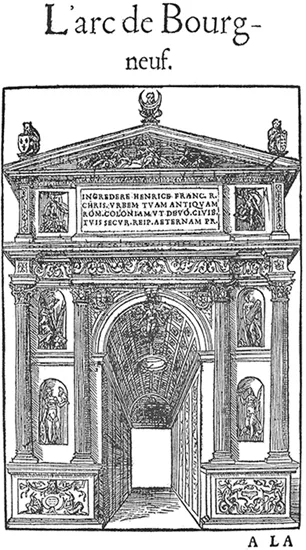

The façade of the triumphal arch at Bourgneuf (Fig. 1.1) displayed niches, in which stood four female statues, each accompanied by an inscription. At the bottom left was Bellona in armour, with one hand resting on a shield, and the other presenting a helmet to the king. In the niche above, counterbalancing War, was a figure of Pax, holding an olive branch in one hand and a torch in the other, with which she sets fire to a pile of weapons. On the opposite side in the upper niche was Concordia, while the fourth niche was occupied by a figure of Victoria, holding her usual attributes of palm branch and laurel crown, which she proffers to the king. Above the entablature were two further niches: on the left stood Mars, sporting sword and buckler; on the right, Jupiter, resting on his eagle and brandishing his thunderbolt. Mars and Jupiter introduce the themes of conquest and world empire, echoed on the arch in Virgilian inscriptions (originally in French, thus much clearer to the crowd, later rendered in Latin in the album). These represent Victory over enemies and the power of ruling: Victory follows War, which ushers in Peace and Concord.20 The subsequent Arch of Honour and Virtue bore an inscription, TERRA TVOS ETIAM MIRABITVR INDA TRIVMPHOS (India itself will marvel at your triumphs), which accompanied the frieze of the triumph of Honour, complete with elephants. The inscription itself is adapted from Ovid’s assimilation of the conquest of India by Bacchus to that by Alexander, focused here on an association between the young Henri and all-conquering Alexander.21

The entry to Rouen of 1 October 1550 was yet more markedly bellicose in flavour, with the parade of young nobility (enfants de la ville) and of guilds, dressed in Roman costume to recreate a classical triumph. This theme of War was occasioned by the Treaty of Boulogne of 28 March 1550, by which the French had recovered Boulogne from England. Apart from elements reproducing the iconography of Mantegna’s Triumphs of Caesar, there were scenes referring specifically to Henri II’s military exploits, one showing legionaries carrying models of captured English forts at Boulogne (Figure 1.2), and another carrying maps of Scotland, where French troops had been engaged against England since 1547.22

Figure 1.1 Façade of the triumphal arch at Bourgneuf (1548)

This series of conquests continued with the capture of Metz, where the king made a royal entry on 18 April 1552, after which the city had to withstand (successfully) a countersiege from the Emperor Charles V, recorded in a tapestry design by Caron.23 The capture of Calais in 1558, after a successful French siege, was finally followed by the royal entry into the town on 23 January 1558. Like his father François Ier, Henri would be mythologised as a victorious monarch, ‘restaurateur de l’art militaire’,24 (‘restorer of the art of war’) as witness the entry to Toulouse of Charles IX in 1565, celebrating Henri as the victor of Metz and Calais, and holding him up as a model to the boy king,25 but adding Charles’s own recent success in the recapture of Le Havre on 29 July 1563, driving out the English garrison. The entry to Troyes contains a poem by Jean Passerat,26 exhorting Charles to conquer England, and to give the throne to his younger brother Anjou, the future Henri III, ‘l’ayant conquis en guerre’ (‘having vanquished him in war’).

This same spirit of world conquest looms large in Charles’s entry to Bordeaux in 1565, where the crowds saw a procession of 12 nations estrangeres captives...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction Ceremony and the Iconography of Power

- 1 The Theme of War in French Renaissance Entries

- 2 ‘Concernant le service de leurs dictes Majestez et auctorité de leur justice’ Perceptions of Royal Power in the Entries of Charles IX and Catherine de Médicis (1564–1566)

- 3 Henri IV as Architect and Restorer of the State: His Entry into Rouen, 16 October 1596

- 4 Warrior King or King of War? Louis XIII’s Entries into his Bonnes Villes (1620–1629)

- 5 ‘Entrate, onoranze, esequie et altre cose’: The Book of Ceremonies of Francesco Tongiarini (1536–1612)

- 6 Re-moulding the City: The Roman possessi in the First Half of the Sixteenth Century

- 7 Theories of Decorum: Music and the Italian Renaissance Entry

- 8 The Grand Entry of Elizabeth of Valois into Spain (1559)

- 9 Elements of Power in Court Festivals of Habsburg Emperors in the Sixteenth Century

- 10 Ephemeral Architecture in the Service of Vladislaus IV Vasa

- 11 The Iconography of Populism: Waterborne Entries to London for Anne Boleyn (1533), Catherine of Braganza (1662) and Elizabeth II (2012)

- 12 The Golden Fleece of the London Drapers’ Company: Politics and Iconography in Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Shows

- 13 Enter the Alien: Foreign Consorts and their Royal Entries into Scottish Cities, c. 1449 – 1590

- 14 A Survey of Recent Research on Renaissance Festivals in the German-speaking Area

- Appendix Leonardo di Zanobi Bartolini Register of Expenses for the Coronation of Leo X, 1513. Transcribed by Lucia Nuti from the Manuscript in the Archivio Di Stato, Rome

- Index