- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Issues in Human Rights Protection of Intellectually Disabled Persons

About this book

This book develops a legal argument as to how persons with intellectual disability can flourish in a liberal setting through the exercise of human rights, even though they are perceived as non-autonomous. Using Ronald Dworkin's theory of liberal equality, it argues that ethical individualism can be modified to accommodate persons with intellectual disability as equals in liberal theory. Current legal practices, the case law of the ECtHR on disability, the provisions of the UNCRPD and a comparative analysis of English and German law are discussed, as well as suggestions for positive measures for persons with intellectual disability. The book will interest academics, human rights activists and legal practitioners in the field of disability rights.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Issues in Human Rights Protection of Intellectually Disabled Persons by Andreas Dimopoulos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Protection of Human Rights for Persons with Disability in Theory: Intellectual Disability as a Distinct Issue

Chapter 1

Intellectual Disability as a Distinct Issue

The Distinguishing Features of Intellectual Disability

The Terminology of Intellectual Disability

Without denying the medical and psychological sides of intellectual disability, modern psychology insists that intellectual disability is a socially constructed concept.1 What it means, how it is measured, and therefore who counts as having an intellectual disability, is historically and culturally contingent. To this day, definitions of intellectual disability vary greatly across countries, according to an array of ideological, political, economic and cultural factors.

For example, from medieval times until the end of the nineteenth century, the social environment, the medical profession and the courts have defined intellectual disability in terms of deficits in what is now described as adaptive behaviour. It was only in the twentieth century that the medical profession insisted in conceptualising intellectual disability as a deficit in intelligence.

Since intellectual disability is socially constructed, the persons regarded as having an intellectual disability will depend on the classification system used by society and the medical profession. The most comprehensive and widely accepted definition and classification system has been devised by the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR). According to the 2002 AAMR definition:

Mental retardation is a disability characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills. This disability originates before age 18.

The AAMR definition then proceeds to furnish several assumptions, which underlie this understanding of intellectual disability. Five assumptions are essential to the application of the definition:

(1) limitations in present functioning must be considered within the context of community environments typical of the individual’s age peers and culture;

(2) valid assessment considers cultural and linguistic diversity as well as differences in communication, sensory, motor, and behavioral factors;

(3) within an individual, limitations often coexist with strengths;

(4) an important purpose of describing limitations is to develop a profile of needed supports;

(5) with appropriate personalized supports over a sustained period, the life functioning of the person with mental retardation generally will improve.2

(2) valid assessment considers cultural and linguistic diversity as well as differences in communication, sensory, motor, and behavioral factors;

(3) within an individual, limitations often coexist with strengths;

(4) an important purpose of describing limitations is to develop a profile of needed supports;

(5) with appropriate personalized supports over a sustained period, the life functioning of the person with mental retardation generally will improve.2

In this sense, intellectual disability is defined as the combination of fundamental difficulties in intellectual functioning and of deficiencies in certain daily life skills. These limitations relate to the present functioning of the person, and are culturally contingent. But intellectual functioning alone is insufficient to classify someone as being intellectually disabled. In addition, there must be significant limitations in adaptive skills – the skills to cope successfully with the daily tasks of living. The concept of adaptive behaviour is linked to what skills would be appropriate for a person’s age and culture.

The assumptions that underlie the AAMR definition are very important because they constitute an effort to reduce the social stigma of being labelled as intellectually disabled. For instance, it is stressed that the purpose of describing the limitations of a person is to provide more accurate support, tailored to the needs of the person. Moreover, the assumptions related to the AAMR definition make it clear that intellectual disability is not necessarily a life-long condition, and depending on the support that society provides, these persons may not be regarded as having intellectual disability all their lives.

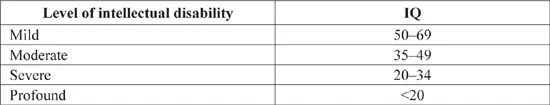

Although the 2002 AAMR classification system does not define levels of intellectual disability, the concept of different degrees of severity of intellectual disability is almost in universal use. These classifications are based on standardised IQ scores, although consideration must also be directed to adaptive behaviour when making a judgement about the level of the person’s intellectual disability. The International Classification of Diseases produced by the World Health Organisation is the most widely used (see Table 1.1).3

Table 1.1 Classification of intellectual disability

The White Paper Valuing People: A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century4 cites rough estimations concerning the general prevalence of intellectual disability in the UK:

Producing precise information on the number of people with learning disabilities in the population is difficult. In the case of people with severe and profound learning disabilities, we estimate there are about 210,000: around 65,000 children and young people, 120,000 adults of working age and 25,000 older people. In the case of people with mild/moderate learning disabilities, lower estimates suggest a prevalence rate of around 25 per 1,000 population – some 1.2 million people in England.5

These figures were updated by the follow-up to that White Paper, Valuing People Now: A New Three-year Strategy for People with Learning Disabilities.6 According to the similar data presented by this policy document, it was estimated that in the UK:

there were 985,000 people with learning disabilities, including 190,000 aged under 20, 127,000 aged 65 or over, and 795,000 adults (defined as over 20 and under 65). Of these, 224,000 were people in England known to social services. The remaining 761,000 people had mild to moderate learning disabilities, may not be known to services, and may not need very much additional support beyond their own families, friends and social networks. However, without information about and access to a range of mainstream services, and help at points of crisis, their needs may escalate to the point where their support networks break down.

It was also estimated that the total number of adults with a learning disability (aged 20 or over) will increase by 8 per cent to 868,000 in 2011 and by 14 per cent to 908,000 by 2021.

This short presentation of modern psychology in the field of intellectual disability illustrates that persons with intellectual disability are a very diverse group, with widely different characteristics and needs. Even though exact statistical data do not exist, persons with intellectual disability form a substantive minority in the English population.

In psychological terms, the disability of persons with intellectual disability consists of low IQ and a lack of adaptive skills; this makes them vulnerable and dependent for help. It is now time to examine how society has responded to this vulnerability.

Social Policy Relating to Intellectual Disability: Normalisation, Self-advocacy and Valuing People

Normalisation Despite the problems which intellectual disability poses to liberal societies, welfare provision and care for persons with intellectual disability are being provided by many social welfare systems. Historically, however, the prevailing social attitude in Europe towards persons with intellectual disability – or to use the language of the past, the feeble-minded – has always been alienation and exclusion from the community. It was only after the extensive atrocities committed under Nazi Germany towards persons with intellectual disability that social attitudes began to change. This, however, did not mean that official discrimination towards intellectual disability perished with the Nazi regime. On the contrary, large-scale policies of involuntary sterilisation of persons with intellectual disability were still being carried out in Scandinavian countries for many years after the war.7

But it became slowly evident in these countries that the quality of life of persons with intellectual disability that were alienated in special homes or asylums was very low. Slowly, a movement concerning the welfare of these persons emerged around 1960, under the wider influence of other similar social movements, such as the civil rights movement in the United States. The social dimension of this movement, known as normalisation, is very evident. Normalisation sought to make normal the life of persons with intellectual disability. The basic aims of the movement were to ensure that persons with intellectual disability enjoyed the same quality of life as everyone else, that they had a lifestyle broken down into time periods of work, leisure and holidays, and that they were awarded the same rights as normal people.8

The grounding of normalisation in basic human and civil rights was reflected in the incorporation of normalisation elements in the 1971 UN Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons.9 For instance, Article 4 of the Declaration holds that ‘If care in an institution becomes necessary, it should be provided in surroundings and other circumstances as close as possible to those of normal life.’ Thus, normalisation did not develop as an isolated ideal, but reflected the prevalent liberal trends of many liberal societies at that time to respond to the demand for equal rights for a number of disadvantaged or minority groups.

During the period in which the concept of normalisation was being developed in Scandinavia, significant changes were also beginning to occur in North America, most notably the civil rights movement and the new label theories in sociology. The North American version of normalisation reflected a growing emphasis upon the importance of the way in which disadvantaged people are portrayed or perceived by the public. This is the reason why this theory of normalisation stresses the importance of the physical presence of persons with intellectual disability, so that they become socially visible and cannot be ignored by society. Consequently, community settings, rather than segregated institutions are of paramount importance. On the other hand, issues of immediate relevance to the quality of life of disabled or disadvantaged groups, such as personal well-being or happiness, and the expression of individual choice, were considered secondary to the social status of the devalued or disadvantaged group as a whole.

In recent years, normalisation has been gradually abandoned in favour of a different approach towards disability. The social model of disability has gained immense popularity among persons with disabilities. It also forms the backbone of the recent UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Yet the influence of normalisation principles can still be seen in the provision of welfare for persons with intellectual disability.

For instance, the aims of the North American normalisation movement are evident in a 1999 US Supreme Court judgment, effectively saying that institutionalisation can be regarded as unlawful discrimination:

Institutional placement of persons who can handle and benefit from community settings perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life.10

Social welfare policy in the UK in relation to intellectual disability: From normalisation values to Valuing People Social, political and financial factors favoured the inception of normalisation in the UK. The concept of community care, and growing public awareness of the dreadful living conditions in long-stay mental institutions, had prepared the ground for the concept of normalisation to emerge in the UK. Normalisation was received as an ideological framework which: (1) was clearly based on basic human values, (2) took account of the social context in which people lived, (3) concentrated on the impact of services on their lives, and (4) challenged the traditional and paternalistic responses which characterised welfare services, and the professionals who ran them.11 These goals became evident in the 1971 White Paper Better Services for the Mentally Handicapped.12 The current White Paper on intellectual disability, Valuing People,13 succinctly summarises the normalisation aims of the 1971 White Paper:

It set an agenda for the next two decades, which focused on reducing the number of places in hospitals and increasing provision in the community. It committed the Government to helping people with learning disabilities to live ‘as normal a life’ as possible, without unnecessary segregation from the community and emphasised the importance of close collaboration between health, social services and other local agencies.14

One of the key goals of the 1971 White Paper was the physical relocation of persons with intellectual disability from long-stay units to community care settings. As large mental hospitals were slowly being shut down, and persons with intellectual disability started flowing into local communities, different sets of problems and challenges started to emerge.

With the physical relocation of persons with intellectual disability in the community a tangible fact, the new challenge is the actual, rather than just the physical, inclusion of persons with intellectual disability within society. Accordingly, the new White Paper on intellectual disability, Valuing People: A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century, marks the turn of the tide for normalisation in the UK, in the sense that the expressed goal of governmental policy is no longer to make normal the life of persons with intellectual disability.

As the White Paper notes:

Very few [persons with intellectual disability] have jobs, live in their own homes or have choice over who cares for them. This needs to change: people with learning disabilities must no longer be marginalised or excluded. Valuing People sets out how the Government will provide new opportunities for children and adults with learning disabilities and their families to live full and independent lives as part of their local communities.15

In all but the name, Valuing People continues...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITY IN THEORY

- PART II THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS FOR PERSONS WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY IN PRACTICE

- PART III THE WAY FORWARD

- Appendix German Civil Code Fourth Book — Family Law Second Title Care and Control (Betreuung)

- Bibliography

- Index