- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

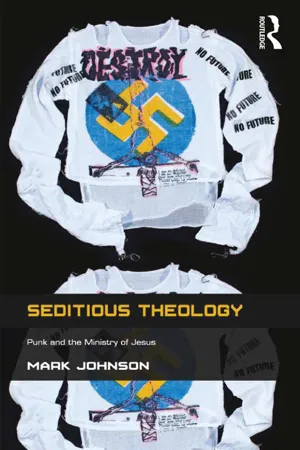

Seditious Theology explores the much analysed British punk movement of the 1970s from a theological perspective. Imaginatively engaging with subjects such as subversion, deconstruction, confrontation and sedition, this book highlights the stark contrasts between the punk genre and the ministry of Jesus while revealing surprising similarities and, in so doing, demonstrates how we may look at both subjects in fresh and unusual ways. Johnson looks at both punk and Jesus and their challenges to symbols, gestures of revolt, constructive use of conflict and the shattering of relational norms. He then points to the seditious pattern in Jesus' life and the way it can be discerned in some recent trends in theology. The imaginative images that he creates provide a challenging image of Jesus and of those who have relooked radically in recent years at what being a 'seditious' follower of Christ means for the church. Introducing both a new partner for theological conversation and a fresh way of how to go about the task, this book presents a powerful approach to exploring the life of Christ and a new way of engaging with both recent theological trends and the more challenging expressions of popular culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seditious Theology by Mark Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

‘Seditionaries’

Chapter 1

Imaging

I start by exploring three of the more important historical factors that contributed to the emergence of punk: the deteriorating situation in Britain, the revolutionary milieu of Paris and the early careers of Malcolm McLaren and Jamie Reid. With this backdrop in place, I then explore punk more directly and focus on the visual expressions of the movement, turning my attention firstly to the clothes that became so emblematic of punk. I shall look at their experimentations with the power of shock and confrontation, the use of the taboo and the harnessing of the latent semiotic power available in everything from simple items of clothing through to potent national symbols. As I engage with these sartorial creations I shall try and discern what such deconstructive gestures may have signified, why such a style became as popular as it did and what it may have demanded of those who chose to adopt it. Having gained a clearer understanding of the clothes of punk, I will then turn to its more graphic face and the work of the artists who provided such a significant contribution to the way in which punk was perceived. To do this, I shall reflect on punk’s artistic ancestry to try and gain a sense of their aesthetic family likenesses, before moving on to see just what they were able to communicate through the methodology of creative destruction. Finally, I will look at some of the more pointed messages that punk art contained in an attempt to understand what they were saying about the country in which they were situated, about modern life more generally and how they went about addressing this through their art.

Fermenting

Painting a representative picture of any period is far from an easy task; as Andy Beckett explains: ‘Hindsight is a great simplifier and the seventies as an era has been simplified more than most.’1 As 1967 drew to a close there was a ‘palpable sense that the optimism and glamour of the mid-1960s had disappeared …’,2 and while for some the dawn of the seventies must have seemed like the turn of a new page, it took little time for such illusions to be dispelled. By autumn 1970, the country was starting to witness its ‘first real slide into chaos …’,3 with the metrics that measured the nation’s health – such as industrial action, inflation and unemployment – all starting to travel in the wrong direction. While 1972 started with the successful signing of the Common Market Accession treaty, after that, the ‘remainder of the year’s news was unremittingly bleak’.4 The winter coal dispute led to scenes of violent unrest, the like of which had rarely been seen before on the British mainland, and the country drifted inexorably towards a political situation as dire as any since the war. By the time 1974 arrived, after years rather than months of strife, a general election resulted in Edward Heath, the aggressor, losing to Harold Wilson, the conciliator. But the promise of harmony through conciliation almost immediately made way for capitulation, as the now-aging Wilson found the ‘continuous search for new ideas an impossible burden’.5 In May 1975, a CBS Evening News bulletin portentously informed its viewers that Great Britain was ‘drifting slowly towards a condition of un-governability’.6 This was a view supported by those commentators at home who were noting that there appeared to be a ‘voracious moral corruption eating at the heart of society’.7 As the year drew to a close Bernard Donoughue, the Prime Minister’s policy advisor, noted in his diary that

Britain is a miserable sight, a society of failures, full of apathy and aroused only by envy at the success of others … this is why we will continue to decline. Not because of our economic or industrial problems. They are soluble. But because the psychology of our people is in such an appalling – I fear irretrievable – state … meanness has replaced generosity. Envy has replaced endeavour. Malice is the most common motivation.8

While the Zeitgeist of despair was at times reflected in the arts, the popular music industry seemed generally content with providing little more than escapism and extravagance, evidenced through size, complexity and visual effect.9 Tellingly, the most financially successful act of the era was almost certainly Elton John, whose record sales ensured that by 1974 his monthly royalty cheques exceeded even those of The Beatles at their peak. Established groups such as Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd produced works of undoubted technical virtuosity and sublime creativity, but their tendency to hold live performances in vast stadia helped to reinforce the sense that the chasm between artists and audience was becoming increasingly wide. This gap between the groups and their fans was very often exacerbated by their lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. As journalist Caroline Coon commented at the time, people ‘saw their heroes photographed in cosy tête-à-têtes with royalty; saw them flaunting their wealth, moaning about tax. Never before was the difference more glaringly obvious between their lifestyles and those of their fans.’10 This performer/audience gap was also revealed, albeit in a different way, by the progressive rock of bands such as Genesis and Yes. Their musically and visually elaborate pieces were undeniably impressive as spectacle and have been unfairly ridiculed for their determination to move away from the formulaic character of chart pop. Yet to many they were not only disconnected from life, they were also becoming impenetrably eccentric. Peter Gabriel’s description of the 23-minute-long ‘Supper’s Ready’ (1972), ‘the ultimate cosmic battle for Armageddon between good and evil in which man is destroyed, but the deaths of countless thousands atone for mankind, reborn no longer as Homo Sapiens’,11 is perhaps a case in point. The glam-rock groups that enjoyed enormous, if transitory, success – such as T-Rex, Sweet and the Bay City Rollers – adopted flamboyant personas in stark contrast to the time in which they were situated and, for a while, they successfully distracted their audiences from their dismal surroundings. Their playful experiments with sexual identity publicly flaunted predilections that, until just a few years previously, had been illegal to act upon and so widened the imaginative horizons of their audience. The problem, however, was that as the decade progressed, the glam-brand looked increasingly out of place, and whilst the theatrical subversion of conventional identities was not without significance, its glamour was out of tune with a time that so clearly needed confrontational criticism as well as diversionary entertainment.12

Alongside these heavy, progressive and glam rock genres, there were artists creating works that, for their time, evidenced remarkable originality and creativity, some of which remain of enduring influence today. One such group, Roxy Music, developed complex and thoughtful work that was arguably ‘in touch with not only a past decadence but also a decadence of today to be celebrated and enjoyed’.13 Unashamedly evidencing their art-school heritage, they provided not simply a significant departure from the orthodox propositions of the pop age but a ‘triumph of the absurd over the boring and mainstream’.14 Equally of note was the work of David Bowie, who almost annually appeared in a different guise. Perhaps the most memorable example was his Ziggy Stardust creation, which, far from being just another pop music persona, allowed him to present concerts that were more like a ‘West End stage show than rock gigs, with special lighting and back-projections, an elaborate set, mime artists, and costume changes’.15 Bowie had taken the conventional rock concert and transformed it into a ‘monument to glittering artifice’.16 We must not, however, confuse such ‘artifice’ with complete detachment from reality, for the album accompanying the concerts – Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972) – demonstrated more than a superficial awareness of the troublesome national situation, even though Bowie had elected to situate his comments in a futuristic apocalyptic framework. The follow-up album, Aladdin Sane (1973), continued to point to this concern for the future with Bowie adding (1913 – 1938 – 197?) to the title track to ensure the listener was only too aware that he believed the decade might contain its own darkly seismic conflict. The problem for both Roxy Music and Bowie was that, as the decade unfolded, their presentations of the alien and the futuristic coincided with the waning of the space-age and came at a time when there were challenges enough on earth.17

Even such a cursory synopsis reveals that any claims that punk arrived into a musical wasteland are overstated, if not inaccurate. Movements such as Pub Rock were injecting energy and enthusiasm to small concert venues that punk would later adopt and develop. Nevertheless, by the middle of the decade, many of the significant acts that I have mentioned were either starting to weaken in their powers or simply disbanding and an expanding vacuum started to appear. Popular music appeared to contain no obvious sense of commentary, no feeling that something was a powerful response to, or reaction against, the era in which it sat. While some of the work, such as glam and Roxy Music, undoubtedly provided a degree of inventive escapism, which could be interpreted as a negative reflection on the way things were, it did so in the act of fleeing the scene rather than standing and confronting the situation head on. What popular music lacked was a ‘prism through which the present and a future could clearly be seen’,18 and by 1976 the contemporary music scene had reached a state of ‘debilitatin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part 1 ‘Seditionaries’

- Part 2 ‘Seditio’

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Scripture Index