![]() PART 1

PART 1

Contexts![]()

Chapter 1

Green Dilemmas

Environment and Economy

Not since the early 1970s, the period known colloquially as the Environmental Crisis, has the ‘environment’ featured so prominently in the popular news media and within mainstream political discourse. This rediscovery of the green agenda has been viewed by many as the rebirth of a distinct political discourse that reflects increased environmental concern amongst the population and a re-engagement with the environmental agenda by politicians and policy-makers. Domestically, the green agendas displayed by all three of the mainstream political parties in the United Kingdom have highlighted the need to tackle environmental degradation. Such a rapid shift in political attitudes towards the environment has been framed almost solely around the need to tackle climate change, a threat perceived as having not only environmental, but crucial social and economic impacts. To this end, the British Government has shifted emphasis away from making an environmental case for action to combat climate change towards an economic argument recently evidenced in the Stern Review on the economics of climate change (HM Treasury 2006). Politically, competition amongst party leaders has been fierce to present the most environmentally sound policies and all parties have highlighted key shifts that will be required to tackle global environmental change, including the use of regulation, financial penalties, incentives and exhortation (Gilg 2005) as means by which to effect change. For example, the Labour administration’s focus on taxing specific ‘environmental bads’ has firmly grounded the principle of penalties in the mind of businesses and commerce. In other instances, policies have been focused around engaging the public in more environmentally sound activities, such as recycling or energy conservation. Yet critics have pointed to the obvious flaws in such strategies, not least the dilemma that lies at the heart of attempting to implement such policies which many have argued will be detrimental to economic progress.

This first ‘green dilemma’ for twenty-first century society can be illustrated with reference to the growing air travel industry within the United Kingdom. Since the late 1990s low cost airlines have emerged as a distinctive force in budget travel, offering frequent flights from an expanding range of regional airports to both domestic and European destinations. What has characterised the growth of such airlines is the vigorous marketing techniques and the use of Internet technology to promote low cost, short-haul air travel. This has witnessed the growth of a range of market segments, not least the major increase in short breaks and city breaks, alongside ‘stag and hen’ weekends, ‘spa breaks’, skiing, rugby, football and golfing pursuits. In many instances, the growth in short-haul air travel has either replaced existing modes of transport, such as rail or coach travel, or has seen the emergence of new markets. In any case, the increase in air travel has had a marked impact on passenger numbers. For example, at London Luton Airport, passenger figures more than quadrupled in the ten years 1994 to 2004 (DfT 2005), due in the main to the low cost airline easyjet. Indeed, the environmental impact of such increased air travel has been the subject of recent vexed debate. Statistics are regularly quoted regarding the amount of kilograms of carbon each passenger will emit for a specific journey. The very act of boarding an aeroplane for whatever duration is contextualised and deliberated according to the environmental damage that this specific act creates. This is presented at the broadest spatial scale and is rarely conceptualised within temporal constraints. The message is therefore a simple one: flying is ‘bad’ (a message now being countered by the first attempts of the airline industry to provide eco-labelling for customers).

Accordingly, the first ‘green dilemma’ we encounter in modern society is the desire for ongoing economic growth alongside an acknowledgement that such economic progress may be causing damage which could have a fundamental impact on the global environmental system. For some, the remedy to this problem is simple: economic reductionism and a move to frugality – even perhaps a move away from capitalism – as a means by which to safeguard future generations from environmental catastrophe. Yet this simplistic message, whilst providing a clear and concise direction for behavioural change, is likely to resonate with no more than a minority of citizens, already committed to the environment.

Human Perspectives: Time and Space

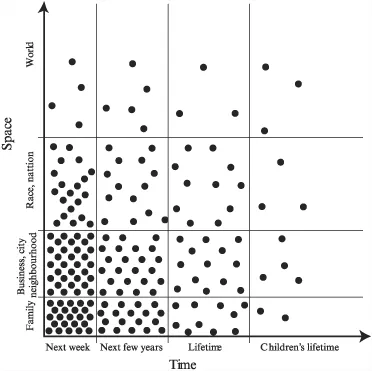

Meadows et al. (1972)1 succinctly demonstrated why this was likely to be the case, by highlighting both the spatial and temporal constraints on human beings to conceptualise and act on environmental threats. Figure 1.1 is adapted from the original suggested by Meadows et al. (1972) and demonstrates how the human ability to perceive and act on threats at the ‘family’ scale and within a short timeframe are acutely sensed, whilst those at a global and generational scale are perceived very weakly. Meadows et al. (1972, 18) argued that such perceptions necessarily varied from person to person, stating that ‘In general the larger the space and the longer the time associated with a problem, the smaller the number of people who are actually concerned about its situation’. Although Meadows et al. argued that such differences in perception would differ according to culture and experience, there is an implicit belief in western societies that the advanced stages of development achieved by many states enables them and their populations to consider global problems in a way that others simply cannot. However, it is becoming widely acknowledged in western societies that concerns expressed at the global level and in terms of generational timeframes have little resonance with the everyday lives and practices of individuals.

Figure 1.1 Human perspectives (after Meadows et al. 1972). Reproduced with the kind

permission of Professor Dennis Meadows

Source: Meadows et al. (1972).

This disconnection between lived experiences in time and space is the second ‘green dilemma’ and what forms the basis for the intellectual and practical challenges that face western societies attempting to grapple with the enormities of environmental issues and their potential amelioration. Goodwin and Barr (2007) have referred to these (multiple) disconnections as the ‘rupturing of scale’, reflected in and between scientific, political and lay discourses on the environment. Within the context of this book, a key dilemma which faces western societies is the ‘rupture’ between the lived experience of ‘environment’ or ‘nature’ and the global context. Eden (1993) has argued that as individuals we have become desensitised to environmental change through the developments in technology that have insulated us from the environment. Apart from the aesthetics of green space in our mainly urbanised living environments, we may only experience ‘nature’ when engaging in tourism and recreation. Even then, this may be a highly sanitised and artificial experience.

In temporal terms, we have become concerned more with our ability to consume and take ownership of resources for immediate gratification. The notion of expending effort and investment for long-term gain has been steadily replaced with a timescale that permits decisions to be taken only at a political timescale of perhaps four to five years. At the individual scale, this is reflected in the common decisions by householders not to invest in energy saving devices and consumables, such as more efficient boilers or light bulbs, because the immediate ‘gain’ is not evident. More widely, decisions to invest in environmental technology or more sustainable infrastructure are sidelined within the political context of the day.

Accordingly, the second green dilemma seeks to emphasise the critical problems of ‘scale’ both the spatial scale of environmental problems, their cause and potential resolution, alongside the temporal scaling of environmental problems within and between generations. It is of course intimately related to the first dilemma (conservation versus growth) because decisions on the level of economic growth are framed at both spatial and temporal scales. The final green dilemma builds on the first two by exploring the role of individuals within the global system, illustrating the inherent tension between individual and societal interests, a topic which will become the main focus of this book.

A Tragedy for Our Commons? Individuals and Society

To explore this last dilemma we must turn to what Garrett Hardin (1968) institutionalised as the concept of the Tragedy of the Commons, a long-established notion of over-consumption which presents as much a dilemma for today’s industrialised societies as it invoked for Hardin’s specific example. Hardin explained a state of resource exploitation and the subsequent impacts with an emotive and effective account of pasture land and grazing. The ‘tale’ begins with what we can term resource equilibrium; each herdsman on the pasture keeps as many cattle on the common as is possible. The equilibrium between resource exploitation (in the form of grass grazed) is maintained due the nature of the society on which the use of the pasture is based. Tribal wars, famines, disease and poaching ensure that the number of herdsmen and cattle remain at a level at which resources can be renewed. However, this ‘idyllic’ (in resource terms) situation comes to an end ‘Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy’ (Hardin 1968, 1244). The ‘social’ stability that Hardin refers to has numerous parallels in contemporary society, and in particular is reflected in the development cycles of nations. Social stability can be represented in terms of both political and social goals. Politically, one can infer the development of stable regimes and democratic government. Socially, perhaps the greatest area of stability in the short term would refer to health, with increasing life expectancies and, in the short term, higher birth rates. In the medium and long terms, social stability is more likely to be a function of welfare, with an increasing emphasis on quality of life, economic prosperity and ‘higher order needs’ (Maslow 1970).

Returning to Hardin’s tale, these changed social conditions alter the implicit instincts of the herdsman. Confronted with more desirable social conditions and stability, Hardin (1968, 1244) argues that ‘As a rational being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain. Explicitly or implicitly, more or less consciously, he asks “What is the utility to me of adding one more animal to my herd?”’ (original emphasis). Hardin makes clear that as a rational economic being, the herdsman’s first instinct is to turn to the gain that he might personally attain from any change in his herd. The answer to this question is clear in Hardin’s eyes. Positively, the herdsman has the benefit of one additional animal, which includes the sale of the animal. Negatively, the over-grazing of one animal is of little consequence, since the over-grazing will be shared by all the herdsmen, thus minimising any impact. Such a calculation inevitably leads the herdsman to consider adding additional animals to the common, since the negative impacts are minor compared to the positive effect of adding animals:

But this is the conclusion reached by each and every rational herdsman sharing a commons. Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination towards which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all. (Hardin 1968, 1244)

Hardin’s tale is a popular one; it is not quantified and does not offer predictive validity in time and space. Yet in the 1960s and today, the resonance which the tragedy of the commons has to resource exploitation is striking. Perhaps one of the most effective illustrations of the tragedy is everyday consumer behaviour. A useful example within this framework would be our use of water resources. The summer of 2006 in the UK witnessed a major crisis in water use in the south east of the country. Drought orders, hose pipe bans and other restrictions were placed on households and businesses in many areas of Kent, Sussex and London. In this context, the day of reckoning, according to Hardin’s tale, is the day when social stability in the form of economic development means that the state and society can afford to enhance lifestyles with consumer products, all of which consume water. Far beyond the basic necessities of drinking and sanitation, which are held within the limits of resource exploitation, each rational human being asks themselves what the utility of washing their car, watering their garden or filling their swimming pool is, against the potential negative impact. As with the herdsmen, the positive impact is considerable: a clean vehicle, a lush garden and a full pool in which to cool off. In a society ‘locked’ into consumption that places symbolic value on consumer products and culturally distinguishes between social strata by the consumer ‘signs’ that are provided by individuals (Bourdieu, 1960), the positive effect of using water to present these signs and symbols of wealth and success are far more preferable than the perceived negative impact of exploitation. Such negative impacts are framed not in relation to overall resource exploitation, but in terms of the economic cost associated with water use. Given the symbolic and sign value associated with what is perceived as water ‘need’, this economic cost is considered acceptable. In addition, in a nation that is generally considered to be temperate and with high levels of rainfall, resource exploitation is not considered an issue. Indeed, the water crisis of 2006 witnessed a range of discourses concerning water use being employed and developed by a range of consumer groups through the media. Perhaps the most dominant of these was the argument that there was only a water crisis because of the mismanagement of resources by water companies. Their inability to prevent leaks and still make profits was seized upon instead of the actual water use of each individual and how this related to supply.

Such an illustration touches the core of the argument surrounding our green dilemmas; so many of the environmental problems that present themselves are, by definition, the result of individual exploitation of resources. Yet they are manifested at the global level and thus appear wholly disconnected from everyday lives and practices. Such a disconnection ensures that these green dilemmas are ones which are framed with suspicion and vigorous debate. The key question that is often posed relates to whether any individual’s action, in the knowledge that it does contribute in some way to exploitation, can have an impact in effecting positive change. The refrain, as we shall see more fully throughout this book, is that ‘yes, but only if everyone participates’.

This final green dilemma (individual–society) is intimately related to the preceding two dilemmas of conservation–growth and time–space. Each poses critical questions related to how individuals relate to society, how environmental issues are framed and the types of lifestyles individuals wish to lead in these contexts. Having established these three dilemmas, we now turn to an examination of how policy has attempted to deal with these dilemmas. First, a framework for analysing environmental policy is outlined. The discussion then moves to a consideration of the political shifts that have framed the current political discourse of environmental issues. Having mapped out these frameworks for analysis, the chapter closes by introducing the structure of this book.

Environment, Society and Policy

Environmental policy has long acknowledged the implicit link between resolving and ameliorating environmental problems and human behaviour. Yet the ‘rendering’ of those environmental issues has long been the subject of debate within policy circles. This ‘rendering’ process (Rose and Miller 1992) refers to the ways in which an entity (such as the environment) is ‘rendered thinkable’ in policy discourse. For example, in reflecting on rural policy, it could be argued that ‘the rural’ as an issue of concern to politicians and policy-makers has undergone a series of rendering processes, defined by the dominant policy-related paradigms at the time. Accordingly, rural policy has been framed in a range of different contexts, from agricultural, economic and productive, to a new political context that defines the countryside in terms of a post-productivist and service-based and social context (Wilson 2001). In the same way, the environment has been ‘rendered thinkable’ through a series of contextual shifts that have enabled environmental issues to be reframed in ecological rather than social or economic contexts.

One clear illustration of this rendering process is the way in which a prominent environmental issue has been framed and reframed in society. Municipal waste was, for most of the twentieth century, a growing environmental problem (Pellow 2003; Weinberg et al. 2002) that reflected society’s increasing reliance on consumables. Yet ‘waste’ as a discourse has been reframed several times. Discourses of waste in western societies have focused around both negative and positive constituents, with ‘waste’ regarded as a...