![]() PART I

PART I

Theorizing the Archive ![]()

Chapter 1

The Archaeology of the Manuscript:

Towards Modern Palaeography

Wim Van Mierlo

As students of poetry, we have conceptions of what a poem is and we have notions of what poetic creation is, but do we actually know how a poem comes into being? There certainly is a poetic tradition going back to the Romantics that sees creation as something mysterious, elevated, ungraspable, issuing almost out of nothing. Shelley’s likening of inspiration to a ‘fading coal’ is probably the most famous expression of this. ‘[T]he mind in creation’, he said, is fuelled to ‘transitory brightness’ by an ‘inconstant wind’, the moment of inspiration powering the brain to perceive a sublime glimpse of the uncreated poem. But inspiration is a fickle, uncontrollable power. To capture that potent but momentary glimpse in language is like chasing the wind. And so ‘when composition begins, inspiration is already on the decline’ (Shelley 1977: 503–4). Composition, for Shelley, is inspiration’s poorer cousin.

During composition, a poet is (I imagine) not always fully conscious of the mental, creative and cognitive processes that allow writing to happen. Yet he cannot be fully unconscious of these processes either. Shelley’s idealized notion of inspiration may strike one as rather remote from the actual experience of writing. A modern poet who refined Shelley’s theory is Robert Graves, who divided the creation of poetry into two distinct phases. In the first phase, the poem flickers into being almost subconsciously, as it is ‘rhythmically formed in the poet’s mind, during a trance-like suspension of his normal habits of thought, by the supra-logical reconciliation of conflicting emotional ideas’. The second phase begins when the poet has emotionally ‘dissociated himself from the poem’ and begins ‘testing and correcting’ it ‘on common-sense principles’, transforming the poem-in-the-rough into something that will ‘satisfy public scrutiny’, all the while making sure that ‘nothing of poetic value is lost or impaired’ (Graves 1995: 3–4). Graves thus significantly broadens Shelley’s understanding of inspiration and spreads it across different levels of emotion and experience. What is significant, however, is that inspiration no longer excludes pen and paper, for, even in the first stage, invention manifests itself directly in writing.

Literary archives allow us to study that writing not only in its finished, but also in its inchoate, embryonic state. The work in progress, contained in drafts and manuscripts, offers fruitful insights in the physical processes that underpin its construction. Critique génétique, a theory and practice devoted to studying drafts, analyses these processes. It emphasizes not the afterlife of the work, when the finished text is released to the public, but what comes before: the avant-texte, the text before it is ‘the text’. As a rich, dynamic network of emergent textual components whose development we can study, the avant-texte encompasses all the stages of literary creation (invention, conceptualization, planning and organization, drafting and revision) and the different modes of writing (note-taking, sketching, drafting, revising and correcting) that take place on a variety documents (notebooks, loose leaves, typescripts, page proofs).

As the manuscripts I will discuss in this essay show, the work of the poet involves a struggle not only with language, but also with paper and ink. Studying the growth of a poem through manuscripts may seem to demystify romantic notions of inspiration. But it cannot completely pass over these notions either. Revision is not only about mechanistic change, or about selecting the right word or expression; it is also about invention.1 Inspiration does not simply precede, but also happens during, composition. Manuscripts are, as Daniel Ferrer observes, the ‘dépôts sédimentaires’ of invention (2011: 53).2

Even so, I shall not contend that by looking into the poet’s workshop one gains privileged access to the poet’s mind. The archive does not offer a way of reclaiming a process that remains unfathomable perhaps even to the poet himself. Yet if we accept that manuscripts can say something about creativity, we need to learn how to read their signs. Louis Hay’s classic adage – manuscripts have something to tell; it is time we made them speak – is still pertinent (Hay 1996: 207). The question that deserves our attention, therefore, is how do we distil the poet’s vision from his revisions? What the archaeology of the manuscript must investigate is the meaning behind the cancellations, insertions, substitutions and overwritings that are layered across the page.

While coming to terms with the creative origins of poetry (using as case studies manuscripts by Wordsworth, Keats and Wilfred Owen), my purpose with this archaeology is to expand the analysis of literary drafts to incorporate a more detailed palaeographical investigation. One of the main goals of critique génétique is to disentangle the temporal aspects of writing from the ‘undifferentiated’ manuscripts in the archive and, via a number of preparatory operations such as ordering, classifying and deciphering, distil from them the avant-texte (de Biasi 2004: 38).3 This process, however, depreciates the manuscript’s spatial attributes, its look and appearance. Once the avant-texte is established, and the writing is ‘lifted off’ the page, the physical dimensions of the document are reduced to a one-dimensional text. Some recent work has moved from the mere deciphering of the words to analysing the graphic signs that are indicative of the processes that produced them.4 Even more so than the actual words and revisions, this palaeographical evidence provides information about the dynamics of composition. The way in which the hand moves across the page and the variations this produces (quick or slow, straight or slanted, spontaneous or contrived) is indicative of the creative intensity that drives the writing. The flow of the writing, the vigour of the pen, the boldness of the cancellations, the positioning of the writing on the page all inform us about not only the circumstances in which the writing took place, but also the characteristic habits (or usus scribendi) of the individual writer (Ferrer 1998: 256). As well as elucidating how the manuscript functions in its own right, this palaeographical information also highlights broader contexts of the biography of the text and the scribal culture that is at work at the time. While critique génétique sees manuscripts as largely private and wholly idiosyncratic productions, writing nonetheless is a cultural phenomenon in which specific practices are shared at certain periods in time (Ferrer 1998: 259–60, 265).

What I mean by the archaeology of the manuscript is not something purely metaphorical; it offers a relevant conceptual and methodological perspective on what is essentially a book-historical matter. The challenges that archaeologists face when they interpret the past are similar to those encountered in the palaeographical analysis of modern manuscripts. The fragmentary writing found in drafts, notebooks, fair copies, typescripts and page proofs is similar to the shards of pottery or other remains of human activity uncovered in an archaeological dig. They are our only means of reclaiming the processes of creation from the past. Archaeology and manuscript studies essentially share the same basic hermeneutic problem: how does one begin to understand the evidence without already knowing what it means? Thus, archaeology as a discipline cannot function without the support of other specialities like history, art history, anthropology, geography, geophysics, archaeobotany and so on. Likewise, the study of literary drafts is not possible without the context of literary history, biography, genre studies, poetics, literary criticism, publishing history, reception history, paper history and the like. More to the point, archaeological research and manuscript studies involve a ‘multistranded and multiscalar process’ – that is, it is not enough to create just one interpretation, but to make ‘sense of the data at different spatial and temporal scales’, particularly as the data is complexly diverse, illusive and frequently conflicting (Hodder 1999: 43, 78, 99). What defines archaeological research are the ‘dynamic, dialectical, unstable relations between objects, contexts and interpretations’ (Hodder 1999: 84); with manuscripts, too, we need to recognize the variable relations between the physical documents, the contexts of their production and the interpretations of the textual and graphic signs. Only by connecting and comparing the evidence can we begin to make sense of what is in front of us.5

Beginning The Prelude

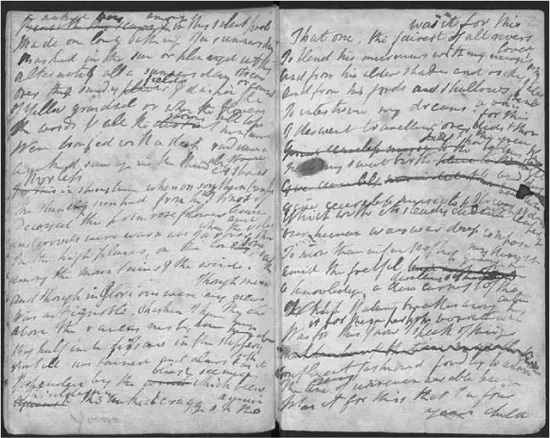

I want to begin elucidating these ideas by looking at the beginnings of William Wordsworth’s The Prelude in MS JJ (Figure 1.1), which is itself a part of Dove Cottage MS 19 (one of four notebooks that William and his sister Dorothy purchased at 1s each in preparation for their extended stay in Germany in 1798), and which contains the now-famous opening lines: ‘was it for this / That one, the fairest of all rivers loved / To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song’ (f.Zr) (1977: 115). These lines, however, pose a particular problem. They occur towards the back of the notebook from which the writing seems to proceed backwards, from the recto on to the corresponding verso and continuing from there on to the preceding pages. Most scholars consider ‘was it for this’ to be the ‘origin’ of Wordsworth’s great poem on the growth of the poet’s mind, even though, when he wrote these lines in late autumn 1789, it cannot have been clear, even to him, what would come from them 50 years hence.

But are they really the beginning? The evidence is not entirely conclusive. MS DC MS19 already contained many other bits of writing composed after Wordsworth had arrived in Goslar. To start a new poem, he needed not only unused space, but also a place that he could easily return to without having to leaf through the whole notebook. The final 11 leaves of the notebook offered that space. Apart from that, the precise sequence remains elusive. Scholars have established that the order of inscription generally moves inwards away from the back in five different stages; within these stages the direction of writing moves mostly forwards, ‘in a zigzag fashion’.6 Sometimes, Wordsworth turned the notebook sideways because the width of the page better accommodated the length of his lines; sometimes, too, he wrote down short sections out of sequence with the rest (1977: 3).7

Why did Wordsworth make work so difficult for himself? Why didn’t he turn his notebook upside down and proceed forwards? This would have made theprocess simpler and more intuitive – moreover, he had done it elsewhere already.8 Could it not be that there is no order at all?

Figure 1.1 William Wordsworth, The Prelude, MS JJ, ff. Yv-Zr [ff. 90v-91r in DC MS 19]

While emphasis in recent scholarship has certainly shifted away from a ‘retrospective perspective’ on the ‘two-part’ Prelude towards a view that the poem grew from ‘a loosely connected sequence of fragmentary blocks of writing’, the assumption remains that ‘was it for this’ was the beginning.9 The reasoning for this, however, was derived not from evidence in MS JJ, but from the order of the poem in two later fair copies: MS V, a copy that Dorothy produced with the assistance of her brother, and MS U, a duplicate copy by Mary Hutchinson, both of which open with ‘Was it for this’.10 The order of poem in these manuscripts is used to ‘reconstruct’ the five-stage sequence in the earlier draft. The sequence in the fair copies, however, was the result of a further creative act by Wordsworth that intervened between MS JJ and the later manuscripts.

Linearity and Revision

Writing is inevitably a linear activity; it purposely moves forward towards the completion of the text. But the operative words ‘forward’, ‘purpose’ and completion are not as self-evident as they appear. Just as origins are difficult to recover, the end the writer strives towards does not predetermine the course by which that end is reached. The composition process, and the trajectory it follows, is marked as much by deviation and indeterminacy as by straight, progressive development.

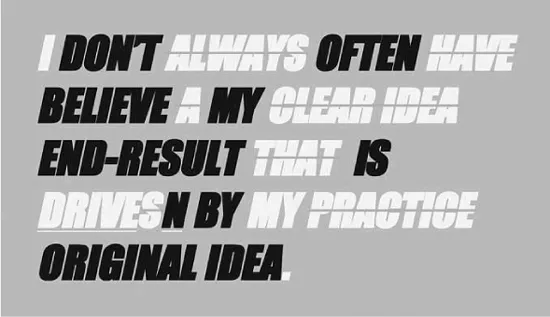

To take these ideas forward – of beginnings, linearity and process, and purpose – I want to look at the ‘Certainty Suspended’ project of the Manchester artist Anne Charnock, a series of ‘work art’ canvases inspired by the ‘track changes’ function in Microsoft Word (Figure 1.2). These works visualize the processes of revision that operate in artistic creation, showing writing as something that is layered and tentative, rather than settled and definite. For Charnock, the intertwining of contradictory sentences gives ‘solidity to her own meandering thoughts and uncertainties’ (Charnock and Clark 2006: n.p.). The example I have chosen, ‘Uncertainty Series No. 1’, specifically presents the idea of prevarication that underlies the process of revision. Between the first statement – ‘I always have a clear idea that drives my practice’ – and the revised statement – ‘I don’t often believe my end-result is driven by my original idea’ – lies a movement that captures the transition from confidence to equivocalness through seemingly unpremeditated discovery. The truth about creation as a process is expressed as much by the revised statement as by the act of revision. And thus, perhaps paradoxically, the original statement, though placed sous rature, remains legible and does not entirely lose its value. This is the double existence of the cancellation, its ‘loss and gain’, ‘emptiness and fullness’, ‘forgetfulness and recollection’ (Grésillon 2008: 88).11 While the original statement has been negated, it has not lost meaning. Hence it remains (or becomes) possible to read the revised statement in relation to the original from whence it came. It is that connection between the two – that present absence – that gives ‘solidity’ to the uncertainty.

Figure 1.2 Anne Charnock, ‘Uncertainty Series No. 1’

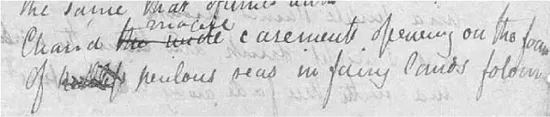

Charnock thus consciously emulates what for any writer is an ordinary experience. Her aesthetics of revision evokes schematically what happens more intricately in a draft. Take, for example, the revisions that Keats made in the autograph manuscript of ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (Figure 1.3; see also Hebron 2009: 138). The changes that Keats introduced are minor, but they add subtle depth to the poem, such as, for example, the change in the seventh stanza from ‘the wide windows opening on the foam’ to ‘the magic casements’. The windows, after all, are not real but imagined, recollected from an auditory vision of the nightingale’s song in ‘fairy lands forlorn’ (Keats 1978: 371). The change is clearly a reasoned change, but not all revisions are like this. Keats’s rapid, almost desultory change of ‘keelless’ into ‘perilous’ in the final line of the penultimate stanza is undoubtedly of a different order.12 This currente calamo revision happened almost without interruption, for ‘keelless’ seems hardly a fitting adjective for the sea.13 ‘Perilous’ is very much le mot juste.

Figure 1.3 Detail of John Keats, autograph manuscript, ‘Ode to the Nightingale’, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 1-1933

What is interesting in Keats’s dynamic of revision is not the choice of words, but the process of choosing, and the fact that we can practically observe Keats’s mind tripping up. Apart from revealing the history of the text’s composition, manuscripts also tell us a good deal about method and craft, about aims, intentions and poetics, about the history and sociology of the text. Keats changing ‘keelless’ to ‘perilo...