eBook - ePub

Learning and Mobilising for Community Development

A Radical Tradition of Community-Based Education and Training

- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Learning and Mobilising for Community Development

A Radical Tradition of Community-Based Education and Training

About this book

Learning and Mobilising for Community Development introduces the reader to different ways of thinking about, and organising community-based education and training within different settings. Stories from the global south and north illustrate approaches to collective learning and collective action. The book provides not only an insight into the how-to of community-based education and training, but through a range of applications, demonstrates the often unspoken shadow side of the developmental work we undertake. The first section of the book outlines the key elements that underpin effective community-based education and training. It then locates community-based education and training within a broader pedagogical project, by tracing the tradition of transformative learning and education. The second half of the book focuses on stories and practice, distilling the application of theory and frameworks. The practitioners within this book emerge from unique and challenging contexts. From civil resistance in West Papua and youth empowerment in South Africa to financial freedom in Australia, these diverse experiences speak to a common quest for social change and justice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Learning and Mobilising for Community Development by Lynda Shevellar, Peter Westoby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A Radical Tradition of Community-based Education and Training

Chapter 1

A Perspective on Community-based Education and Training

Community as Dialogue and Collectivity

Within normative community development processes people come together because they share some common concern. This ‘coming together’ usually emerges organically – people find one another within their existing networks, or it can happen purposefully – someone such as a community worker, leader or activist enables it to happen through networking and inviting people to come together. In this process of coming together people discover the possibilities and potentials of cooperation. People learn or realise that what they could not do or make sense of alone, they can do as a group. Within community development methodology a key part of this process is the shift from what is sometimes understood as ‘I’ to ‘We’. It is a critical shift, a significant movement. It is the formation or construction of community (Brent 2009).

We use the word community here synonymously with the collective, but with a key caveat. For us, community as a collective signifies the ‘in-between’ space of individuality and a kind of collective ‘group-think’. Therefore, we are careful in using the concept of collective taking heed of Martin Buber’s (1947, 2002: 37) warning that ‘Collectivity is based on an organised atrophy of personal existence ... [it] is a flight from community’s testing and consecration of the person, a flight from the vital dialogic, demanding the staking of the self, which is in the heart of the world.’ Community then is carefully theorised as a form of collectivity in which individuals are not collapsed into group-think; it honours the individuals, but enfolds it within a mutual process of dialogue and participation with others.

It is important to understand this ‘in-between space’ – between individuality and group-think – that enables groups to form and in which individuals, conscious of their mutual relationship with others, create spaces for both learning and action. For us, holding such a space requires a deep understanding of dialogue within community-based development work. Such understanding builds on two key ideas of Buber, each of which is now discussed.

I-It vs. I-Thou: Mutuality within Development Practice

At the crux of Buber’s contribution to an understanding of dialogue is his seminal work I-Thou (1958). Our reading of this work leads to an argument that there are two key ways of experiencing the world generally and relationships specifically. The first, characterised as I-It is understood as an experience of object-subject. In a community-based education and training context this would occur if, for example, a government agency, social movement organisation (SMO) or a development practitioner decided that ‘a community needs some training’. The community in this case is objectified – perceived as ‘it’: some passive ‘other’ that requires intervention.

In contrast, Buber discusses subject-subject relations as I-Thou. They are characterised as relations of mutuality, equal exchange, and connection. Within this latter kind of relationship, people or communities are referred to not as clients, customers or consumers, but as people, constituents and co-creators in a learning and action process. The emphasis is on the mutuality and reciprocity potentially embedded in all relationships. Such a shift entails developing a philosophical orientation, or more aptly, an attitude towards self and other that is characterised by a dialogical connection of mutuality and reciprocity. To imagine such relating is to imagine opportunities for re-humanising, which re-centre people as active agents making decisions, using their creativity, resources, relationship and intelligence. An I-Thou relationship is a space that focuses our efforts on relationship building, storytelling, deep listening and building a shared commitment to change.

The Structure of Dialogue: Building Connection and Commitment for Change

Part of the challenge of creating space for the possibility of community as dialogue, and therefore resisting group-think forms of collectivity, is to have some understanding of the structure of dialogue. Such understanding enables people to become technically adept in at least creating the conditions in which community can be fostered, and the kind of community-based education and training that we envisage can occur.

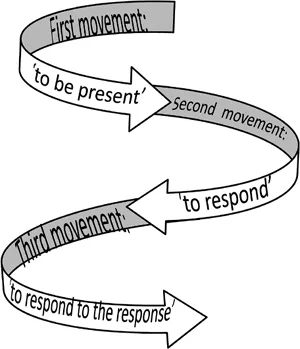

One element of the structure of Buber’s dialogue has previously been interpreted and described technically in terms of first, second and third movement (Kelly and Burkett, 2008) and has been articulated and drawn here to offer directionality for community practice. As interpreted by Anthony Kelly and Sandra Sewell (1988), Buber identified three connected and enfolding ‘movements’ in our dialogue with others. The idea of three enfolding movements clarifies a dynamic process. For instance, ‘first movement’ interaction ‘occurs when we present ourselves to another, or others...we say hello, say who we are and why we are there’ (Kelly and Burkett 2008: 49). ‘Second movement’ dialogue occurs when there is a response from the other to our first movement statements (Kelly and Burkett 2008). ‘Third movement’ dialogue ‘occurs when there is a response to the response’ (Kelly and Burkett 2008: 50). It requires practitioners to be attentive to what is being said, to listen for and connect with what is being communicated. Genuine dialogue, in Buber’s usage, necessarily goes through all three movements, folding back and forth in reciprocal fashion. Buber describes this process of establishing ‘mutual’ relationships as a condition of moving from ‘I’ (first movement) to ‘You’ (second movement) to ‘We’ (third movement) (Figure 1.1).

Adapted from: Kelly and Burkett 2008, Westoby and Owen 2010.

Figure 1.1 The movement structure of dialogue

The challenge of understanding and applying such structure in dialogue is to be ever attentive to the perspective of people encountered. Many people remain ‘stuck’ in first and second movement exchanges returning constantly to their own agendas, unable to enter the other person’s world. There is, therefore, minimal possibility of understanding the world of the other, of grasping their experience or perspective. Clearly, such dialogic structure is pertinent when imagining community as dialogue within education and training settings. Many such settings are structured as hierarchical institutions, or foster hierarchical dynamics that do not create spaces where people can necessarily listen deeply to one another responding to the issues of the ‘other’. People, focused on their ascribed roles as leader, trainer, teacher, development expert and so forth, are often unable to encounter one another in dialogical relationship with an orientation to understanding each other’s different worlds. It is our sense that some of the more contemporary thinking around participatory approaches to learning, such as articulated by Chambers (2007), and Kumar (2002) are trying to create, via participatory techniques, spaces and platforms which enable such listening and connecting. For us, Buber’s ideas provide a philosophical take on how to understand what Chambers and Kumar are trying to achieve.

Community-based

Having discussed our understanding of community and dialogue we now turn to the notion of ‘community-based’. In writing a book about community-based education and training we ask the question: What does it mean to be community-based? The perspective we bring is that ‘community-based’ signifies two key ideas. The first is that ‘community-based’ signifies the importance of the learning process connecting at a ‘grassroots’ level. The second idea is to think of ‘base’ in terms of ‘people in place ‘taking responsibility’ (Kelly and Sewell 1988: 49). Each of these ideas is now discussed in turn.

In the terms of the first idea, to undertake community-based education and training, rather than organisational-based or sector-based training, is to be involved in training that takes place amongst people who directly have a concern within their locality, or within their interest or identity group. In the same way that community development is different to sector development, or organisational development – in that the word ‘community’ signifies not only a dialogical relationship, but a connection at the grassroots within development work – so it is in education and training work. If training is conducted amongst a group of professionals working within a service delivery organisation, then it is not ‘community-based’ education/ training, it is professional-based or sector-based training.

The second idea signified by ‘community-based’ is that of thinking about base in terms of taking responsibility. We draw on a useful framework again originally articulated by Kelly and Sewell (1988: 42) as ‘space, place, and base’. Within this framework space is understood as a geographical area in which people live or are located. Some people simply occupy space – for example, they dwell in a space, come and go to work and home, but have little connection to it. However, for some people the relationship to space shifts as they develop a sense of connection to the space, and derive a sense of belonging. The space now thought about as a place, rather than just space is a part of their identity (Kelly and Sewell 1988: 47). Furthermore, some people not only derive a sense of belonging from a place, but also decide to take responsibility for it. Within the framework, at this point such people have made the location their base. In a sense then some people live in a space, derive a sense of belonging from the place and make it their base by taking responsibility for it (Kelly and Sewell 1988: 49). Drawing on such a framework enables us to imagine the base dimension of community-based education and training as signifying that a group of people have decided to take some responsibility for a space/place. They are not just located at the grassroots – a colloquial way of talking about local-level community concerns – but are also responsible actors within this grassroots location.

Having provided some settings as to how we understand community as dialogue and a particular kind of collectivity, and also clarifying the ‘base’ of community as linkages at the grassroots with people taking responsibility, we now turn to the concepts of education and training.

Community-based Education and Training

As alluded to within the Introduction, it is the combination of both the learning and action elements that highlight the meaning of education and training within this book. Also, when referring to action the focus is not on technical or vocationally-oriented action but more radically-oriented action. The integration of learning and action within a radical tradition of education and training has been articulated in an accessible way to community workers by Hope and Timmel (1984), and recently reclaimed by Brookfield and Holst (2011). The latter go on to argue that the ‘term training has suffered a downgrading to the point that...many adult educators in North America [and elsewhere]...avoid using the word’ (Brookfield and Holst 2011: 66). In tackling this avoidance head on, and as part of reclaiming the radical idea of training, Brookfield and Holst (2011) take the time to both review the many contemporary narrow definitions of what is generally considered to be training today, and then to also overview historical and contemporary examples of training within the radical tradition.

Brookfield and Holst (2011) note that training is often used within discourses of vocational and workplace training. The focus of such training is often on instruction and the underpinning philosophy is usually a neoliberal political economy, that is, training needs are driven by employer needs. In contrast, an alternative reading of the training landscape provides examples of training being used within the radical tradition – often focused more on democratic and participatory processes. For example, Brookfield and Holst (2011) discuss, among others: the Highlander Folk School with its focus on leadership training and training for citizenship; the Citizenship Schools of the 1960s and their training of teachers; the Sandinista National Literacy Crusade in Nicaragua, focused on training local people and local leaders; and Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement, with its training of people in co-operatives.

In distilling the practices of such a radical training tradition they identified the following key themes:

• training as the mastery of action (practice) and the mastery of principle (theory) conceived dialectically

• a central element is affective and relational – building the skills, understanding, and confidence of people

• a significant amount of training takes place in the actual activities of social movements: it is training in action

• training is a mutual relationship where both the trainer and the trainee are trained

• training is participatory and democratic in methodology

• training is not neutral: it is oriented to serving the needs of specific sectors of society; it attempts to advance social change activism towards a more participatory and democratic society; it is, therefore, as much a political act as it is a pedagogical act (Brookfield and Holst 2011: 85).

This description of key practices resonates well with our perspective of training and education practices.

It should also be said that many community development processes implicitly hold both processes of community learning and action. Indeed, the stories of Parts II and III of this book might for many feel like, or read like, community development or community mobilisation stories (which they are). However, this book emphasises work that makes the learning explicit within the action processes, hence another reason for our reclamation of the notion of training. There is a mandate to train; to make learning integral to the process of acting. Community practitioners using a reclaimed understanding of a radical tradition of education and training processes are concerned with how a collective of people (noting our previous caveat about collectives) are learning, and then translating that learning into action. Community-based education and training is infused and enthused with an ethos that is both learning and action-oriented.

At this point the kind of community learning and action that community-based education and training might lead to has not been discussed. In many ways, this will be determined by the mandate of the trainer and the kind of framework that a trainer is drawing on. The different stories of Parts II and III will contextualise different approaches available to the practitioner and provide a sense of the diverse kinds of learning and action that can emerge. However, for the purposes of this chapter we will explain or deconstruct one simple framework that captures the types of knowledge and the roles of educators or trainers that guide much community-based learning.

Types of Knowledge

Patricia Cranton’s delightful book Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning (2006) introduces readers to Habermas’s (1971) work on knowledge and its application to transformational learning. Her re-articulation of Habermas’s work provides us with a useful framework for thinking about the kinds of knowledge being generated that would be driving the collective learning and action process within community-based work. The Habermas framework considers three types of knowledge: technical; practical and emancipatory. Each is discussed in turn and is considered in the light of what we have said previously.

Technical knowledge, sometimes named instrumental knowledge, is focused upon learning a concrete and technical skill. Often there are some kinds of scientific laws embedded within this kind of knowledge. If, for example, a group of people who have come together for collective action around a common concern decide that their action requires learning computer skills, then this could be conceptualised as the acquisition of a technical set of skills. Or, to take another example, if a group of people as part of their action, were designing a longer-term project and decided they needed so...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: A RADICAL TRADITION OF COMMUNITY-BASED EDUCATION AND TRAINING

- PART II: AUSTRALIAN STORIES OF PRACTICE

- PART III: INTERNATIONAL STORIES OF PRACTICE

- PART IV: GATHERING THE WISDOM FROM THE STORIES

- Index