eBook - ePub

God and Nature in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

God and Nature in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish

About this book

Only recently have scholars begun to note Margaret Cavendish's references to 'God,' 'spirits,' and the 'rational soul,' and little has been published in this regard. This volume addresses that scarcity by taking up the theological threads woven into Cavendish's ideas about nature, matter, magic, governance, and social relations, with special attention given to Cavendish's literary and philosophical works. Reflecting the lively state of Cavendish studies, God and Nature in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish allows for disagreements among the contributing authors, whose readings of Cavendish sometimes vary in significant ways; and it encourages further exploration of the theological elements evident in her literary and philosophical works. Despite the diversity of thought developed here, several significant points of convergence establish a foundation for future work on Cavendish's vision of nature, philosophy, and God. The chapters collected here enhance our understanding of the intriguing-and sometimes brilliant-contributions Cavendish made to debates about God's place in the scientific cosmos.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God and Nature in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish by Brandie R. Siegfried,Lisa T. Sarasohn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: The Duchess and the Divine

Margaret Lucas Cavendish was a wide-ranging thinker, a polymath whose adventurous mind refused to give way to the restrictive social expectations of her sex. The demure apologia for publication typical of women in the seventeenth century—which relied heavily on ideals of Christian piety and female submissiveness—was simply not for her. Nor was she willing to spend her intellectual efforts modestly translating work developed by others, but rather forthrightly claimed for herself the right to attempt the kind of glory typically associated with much-admired literary and historical figures, such as Hector, Achilles, Ulysses, Alexander, and Caesar. Indeed, after prefacing her books with both fashionable humor and serious intent, she unabashedly sent special copies of her volumes to be archived at universities for the benefit of future posterity. Something of a celebrity in the period, she was read by many of her contemporaries, corresponded with several prominent natural philosophers, and was frequently the focus of socially observant chroniclers, such as Samuel Pepys.

Cavendish’s works continued to be popular among members of subsequent schools of thought—such as the Romantics and the Modernists—who read her biographies, poems, and letters attentively. After a lag of interest in her writing during the mid-twentieth century, the revival of her work by feminists specializing in literature, art, political history, philosophy, and the history of science has returned Cavendish to the stage of intellectual inquiry. Still, perhaps precisely because she eschewed the religious focus typical of early modern women authors defending their right to publish, an especially intriguing theme common to several of Cavendish’s many works has received little attention: her speculations on theology’s significance for the study of nature.

Cavendish’s intensifying interest in science and theology is readily visible in Sociable Letters (1664). In letter 157, for instance, she defends her theory of physics in the context of divinity: “Those that take Exceptions at my Philosophical Opinions, as for Example, when I say there is no such thing as First Matter, nor no such thing as First Power, are either Fools in Philosophy, or Malicious to Philosophy” (emphasis added). Her position, she asserts, is upheld by the very nature of God, since “Infinite Power, it is in God, and God hath no Beginning, nor his Power, being Infinite and Eternal.” Indeed, “as for Matter … being in [God’s] Infinite and Eternal Power, [it] is also Infinite and Eternal, without Beginning or Ending.”1 These ruminations follow hard on the heels of Letter 156, in which—after a long discourse on the anatomical relation between nerves and sinews and their relative functions and oddities—Cavendish opines that “what is good to Strengthen the Sinews and Nerves, is Hurtful, and apt to Obstruct the Liver, Splene, and Veins, so as the Remedy may prove worse than the disease.” Within the space of only two letters and a few dozen lines, the breadth and depth of Cavendish’s interests are on full display: anatomy and physiology, diet and nutrition, medicine and diagnostic procedure, natural philosophy and theology—these are but a few of the topics through which she ventures with intellectual enthusiasm, self-deprecating humor, and literary creativity. Equally apparent in this and her other works is a wry bellicosity that took the shape of parody, satire, and witty caricatures of some of her peers.

Thanks to her bold determination to publish her works as soon as she wrote them—letting her philosophical ideas and literary devices blossom in the public eye, so to speak—many of her contemporaries found themselves considering her observations in the course of their own studies. For instance, Nehemiah Grew—who as Katie Whitaker points out, “would later pioneer the study of plant anatomy and become secretary of the Royal Society”—closely studied the first edition of Cavendish’s Philosophical and Physical Opinions and drew up “a detailed, eight-page summary of Margaret’s book” (Figure 1.1).

Moreover, Whitaker continues, Cavendish’s “philosophical friends—Constantijn Huygens, Walter Charleton, and John Evelyn—all engaged in lengthy discussions with her, either face to face, or by correspondence.”2 Whitaker’s book broke new ground in Cavendish studies, tracing the vibrating web-work of mutual influence in which Cavendish socialized and wrote—something which had not been explored much in the early scholarship, when those interested in Cavendish’s writing found themselves devoting much of their energies to making the case for its literary and philosophical merit. Lisa Sarasohn’s recent book, The Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish: Reason and Fancy during the Scientific Revolution, provided a focused philosophical depth to Whitaker’s historical breadth.3 The most thorough extended analysis of Cavendish’s natural philosophy to date, Sarasohn’s work gives robust corroboration to the appropriateness of Cavendish’s recent popularity among writers in philosophy, history, literature, political theory, and cultural history.

Thanks to the work of scholars such as Sarasohn and Whitaker, treatments of Cavendish’s ideas on God and nature have become more nuanced. Additionally, over the course of the last thirty years, much has been done to recalibrate our understanding of the broad theological contexts within which Cavendish and her peers developed their views. Seventeenth-century studies in chemistry, physics, biology, astronomy, and medicine—and the technologies that could be developed from the study of each—were more often than not embedded in rhetorical contexts rife with explicitly religious apologia. In England, the members of the Royal Society rejected the enthusiast religious trends that had contributed to the English Civil War and instead embraced a Latitudinarianism that anchored natural philosophy to faith, while preventing any given religious dogma from hampering the development of new knowledge.

Fig. 1.1 Frontispiece to Margaret Cavendish, The Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655). Pieter van Schuppen, after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, “Studious She is and all Alone.” Engraving of Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673), Duchess of Newcastle. This item is reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

The intention of the present volume is not to set forth a general overview of the various religious movements, theological debates, and spiritual attitudes that defined the culture in which Cavendish lived; that work has been done elsewhere. Suffice it to say that our understanding of the life and work of famous figures such as Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, and Isaac Newton—recognized giants in the advancement of learning—has clearly benefited from the reappraisal of early modern science’s theological moorings, and it can be fairly anticipated that similar gains will be made in Cavendish studies. We now know, for instance, that a good portion of Newton’s writing in his unpublished notebooks focused on religious topics, and his work on natural philosophy in these contemplations was often subordinated to that emphasis. In his correspondence, Newton acknowledged that in writing the Principia, he “had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity.”4 Thinking about Newton in relation to Cavendish is also a useful reminder that in the drama of the scientific revolution, the major players were often of two minds about their own hypotheses. “It is important to recall that scientists themselves have often been dubious about some of their own theoretical constructions,” Ernan McMullin explains.

The most striking example of this sort of hesitation is surely that of Newton in regard to his primary explanatory construction, attraction. Despite the success of the mechanics of the Principia, Newton was never comfortable with the implications of the notion of attraction and the more general notion of force. Part of his uneasiness stemmed from his theology; he could not conceive that matter might of itself be active and thus in some sense independent of God’s directing power … how were these forces to be understood ontologically?5

Whereas Newton had the math but was uneasy with the implications of matter’s seeming self-direction, Cavendish scarcely had any math but was quite certain that matter had substantial forms of freedom. And although her notion that all matter is self-knowing and self-moving would not seem particularly extravagant to modern physicists and biologists for whom matter is inherently capable of self-organization or “emergence,” it was certainly a fraught concept for even Newton in the religious environment of the seventeenth century.6

Boyle’s The Excellency of Theology (1674) gave Newton much to ponder in this regard, for as Newton’s well-respected senior in the Royal Society insisted, the “light of nature” provided the encompassing illumination of a “universal hypothesis”:

The gospel comprises indeed, and unfolds the whole mystery of man’s redemption, as far forth as it is necessary to be known for our salvation: and the corpuscularian or mechanical philosophy strives to deduce all the phaenomena of nature form [sic] adiaphorous matter, and local motion. But neither the fundamental doctrine of Christianity, nor that of the powers and effects of matter and motion, seems to be more than an epicycle (if I may so call it) of the great and universal system of God’s contrivances, and makes but a part of the more general theory of things, knowable by the light of nature, improved by the information of the scriptures: so that both these doctrines, though very general, in respect of the subordinate parts of theology and philosophy, seem to be but members of the universal hypothesis, whose objects I conceive to be the nature, counsels, and works of God, as far as they are discoverable by us … in this life.7

While Newton considered how best to elucidate “Principles” for thinking men that meshed with “the belief of Deity,” Boyle straightforwardly presumed faith to be the vantage point from which nature’s chemical structures could best be seen.

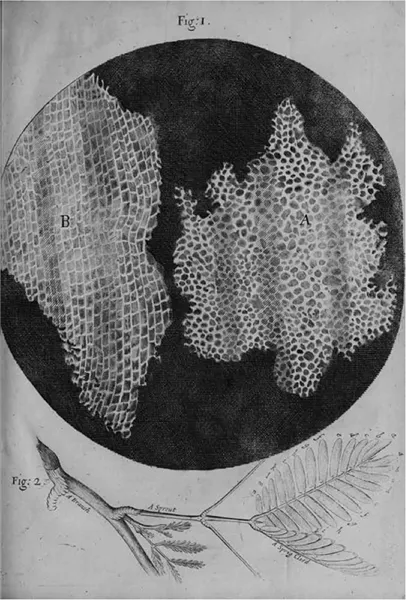

In a similar vein, Robert Hooke saw the Royal Society’s work as the fulfillment of biblical prophecies. The son of a curate, Hooke succinctly advanced the prophetic character of the experimental philosophy in his Preface to Micrographia (1665): “And as at first, mankind fell by tasting of the forbidden Tree of Knowledge, so we, their Posterity, may be in part restor’d by the same way, not only by beholding and contemplating, but by tasting too those fruits of Natural Knowledge, that were never yet forbidden.”8 We see this highly religious frame of mind at work in the famous “Observation XVIII” of Micrographia where Hooke coins a word for micro-structures based on the architecture of contemplative devotion. Viewing thin slices of cork through his microscope, Hooke explains, “I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous … these pores, or cells … were the first … that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this.” Hooke gave to modern science a word that captured the architectural analogy that leapt to his mind: the boxlike micro-structures of plants reminded him of the cells of a monastery (Figure 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 Drawing of cork from R. Hooke, Micrographia, 2nd ed. (London, 1667). By kind permission of the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Though the natural world, human nature, and the Divine were all intimately connected for Cavendish and her contemporaries, there was little agreement as to precisely what role God played in the detailed scheme of things. Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle, and Robert Hooke grounded their studies in natural theology, as did many of their empiricist contemporaries: the natural world, they assumed, testifies to God’s creative and providential plan. Although Cavendish disagreed with each of these thinker’s premises regarding experimental philosophy’s particular abilities to advance an understanding of God, she shared with them a sense that the nature of God was worth intellectual regard and focused effort. She nevertheless brought a robust skepticism to the table. On the one hand, she firmly believed that the instruments of experimental science were as likely to distort as to reveal creation: God was not under the lens. On the other hand, Cavendish embraced a notion of the divine as that which subtends the physical world and, consequently, could not be ignored in science’s considerations of nature. Furthermore, while the fact of nature opens the door to rational inquiry and theological speculation, Cavendish felt that the ongoing immanence of nature—its potentialities emerging into and fading out of actuality in eternal cycles of regeneration—invites fancy’s entrance into the halls of knowledge. For this reason, a qualitative characterization of Nature as a living, self-conscious entity underlies Cavendish’s natural philosophy, and the relationship between Nature and God inevitably frames her various speculations on topics such as chemistry, perception, the physics of motion, the qualities of matter, theories of humanity’s fundamental nature and the form of government best suited for it, and the modes of critical inquiry appropriate to the study of each. Several essays in this volume treat of these topics in relation to the literary genres Cavendish used to prudently frame, pleasurably enhance, and provocatively assert her views on God, philosophy, and science.

As reevaluations of seventeenth-century natural philosophy’s entanglement with theology continue to develop, similar considerations relating to the works of Margaret Cavendish will no doubt see a corresponding expansion. In the meantime, scholarship on Cavendish has tended to fall into one of three categories: (1) considerations of her contributions to contemporary theories of natural philosophy and the scientific revolution; (2) expositions and analyses of her experiences of civil war, royalist exile, and return to England with the Restoration; and (3) evaluations of her innovations as a female author who challenged the gender ideology of her day. This volume adds another dimension to Cavendish studies by exploring the theological threads woven into her ideas about Nature, matter, magic, governance, and social relations, with special attention given to Cavendish’s literary oeuvre. The essays collected here enhance our understanding of the intriguing—and sometimes brilliant—contributions Cavendish made to debates about God’s place in the scientific cosmos.

Still, as the variety of viewpoints represented in the subsequent essays attest, though Cavendish’s thoughts often yield heady intellectual distillations, she seems to have resisted the final act of bottling them for easy categorization and storage. Hence, a certain amount of caution should be used when considering the theological implications of Cavendish’s philosophy. As Hilda Smith argues in “Claims to Orthodoxy: How Far Can We Trust Margaret Cavendish’s Autobiography?” Cavendish shared her fellow royalists’ disdain for religious enthusiasts, whom the duchess blamed for instigating the English Civil War and for the social upheaval that followed in its wake. Impressed neither by the rites of piety nor by the roles of priests and pastors, Cavendish frequently targeted both for satirical treatment. She was, in short, an independent thinker. As Smith further argues, contrary to the shy and retiring damsel figured in the biography, Cavendish regularly asserted her will in a variety of arenas—social, economic, philosophical, and even medical. Those autonomous and insistent tendencies sometimes resulted in fractious entanglements and, at least once, in outright legal accusations against the duchess. Of special note in Smith’s discussion is the detail with which Cavendish’s interest in physiology and medicine is documented in the historical record, material sorely in need of further scholarly attention.

As an additional aid in maintaining the productive historical circumspection suggested by Smith, Sara Mendelson’s essay, “The God of Nature and the Nature of God,” provides a survey of four interrelated contexts that must be taken into account when considering Cavendish’s view of God in relation to natural philosophy, including key biographical elements, contemporary religious debates and trends, Cavendish’s use of known literary conventions in relation to her own interesting innovations, and the actual questions and assertions developed within the various genres she employs. Mendelson’s essay is particularly useful in emphasizing just how prolific Cavendish was: her experiments in form are as interesting as her criticisms and contemplations of experimental philosophy. Moreover, Mendelson’s overview of how and why certain aesthetic forms were associated with particular religious debates reveals both the currency and creativity of Cavendish’s thinking among her seventeenth-century peers. This is useful as a backdrop against which the diversity of Cavendish’s theological interests can be evaluated. As the subsequent essays attest, Cavendish’s range of inquiry was broad, her penchant for philosophical venturing lively, and her desire to defend her ideas persistent and vigorous.

Joanne H. Wright’s essay, “Darkness, Death, and Precarious Life in Cavendish’s Sociable Letters and Oratio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Note on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations for Works by Margaret Cavendish

- Chapter 1 Introduction: The Duchess and the Divine

- Chapter 2 Claims to Orthodoxy: How Far Can We Trust Margaret Cavendish’s Autobiography?

- Chapter 3 The God of Nature and the Nature of God

- Chapter 4 Darkness, Death, and Precarious Life in Cavendish’s Sociable Letters and Orations

- Chapter 5 God and the Question of Sense Perception in the Works of Margaret Cavendish

- Chapter 6 Paganism, Christianity, and the Faculty of Fancy in the Writing of Margaret Cavendish

- Chapter 7 Fideism, Negative Theology, and Christianity in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish

- Chapter 8 Brilliant Heterodoxy: The Plurality of Worlds in Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World (1666) and Cyrano de Bergerac’s Estats et Empires de la lune (1657)

- Chapter 9 “A double Perception in All Creatures”: Margaret Cavendish’s Philosophical Letters and Seventeenth-Century Natural Philosophy

- Chapter 10 Natural Magic in The Convent of Pleasure

- Chapter 11 Margaret Cavendish’s Cabbala: The Empress and the Spirits in The Blazing World

- Chapter 12 Margaret Cavendish and the Jews

- Chapter 13 “Soulified”: Cavendish, Rubens, and the Cabbalistic Tree of Life

- Appendix A Bibliographic Note: Cyrano’s Estats et Empires de la Lune and Cavendish’s Blazing World

- Bibliography

- Index