- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Transformations: Centres, Peripheries and Systems

About this book

Definitions of urban entities and urban typologies are changing constantly to reflect the growing physical extent of cities and their hinterlands. These include suburbs, sprawl, edge cities, gated communities, conurbations and networks of places and such transformations cause conflict between central and peripheral areas at a range of spatial scales. This book explores the role of cities, their influence and the transformations they have undertaken in the recent past. Ways in which cities regenerate, how plans change, how they are governed and how they react to the economic realities of the day are all explored. Concepts such as polycentricity are explored to highlight the fact that cities are part of wider regions and the study of urban geography in the future needs to be cognisant of changing relationships within and between cities. Bringing together studies from around the world at different scales, from small town to megacity, this volume captures a snapshot of some of the changes in city centres, suburbs, and the wider urban region. In doing so, it provides a deeper understanding of the evolving form and function of cities and their associated peripheral regions as well as their impact on modern twenty-first century landscapes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Anatomy of Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean Region: Case of the Girona Districts, 1979–2006

Introduction

This chapter explores the urbanization process in the Girona districts of Spain between 1979 (the year of incorporation of the democratic councils) and 2006, the year immediately prior to the recent recession. This area, located northeast of Barcelona, offers a significant illustration of the recent transformations that have affected not only Spain but also the western Mediterranean coast as a whole. The work undertaken in this chapter focused on the analysis of zone development plans, the documents that regulate zoning under the local development framework in each new area of developable land. A zone development plan shows the layout of the zone and contains an explanatory report, including basic information on land use, area, the number of proposed housing units and the developer. The interpretation of the results was based on two complementary scales. The regional scale is the appropriate level at which to understand the dynamics of urban sprawl; while analysis at the scale of particular places facilitates interpretation in terms of a morphological typology. A study of this kind is a pioneering study in Spain because of the time dimension (almost three decades) and the magnitude of data analysed (211 Municipalities and 522 Zone Development Plans).

The Political, Economic and Social Framework: From Desarrollismo to Globalization

Desarrollismo, or development at all costs, was the Spanish version of Fordism during the Franco regime, involving high growth associated with industrialization and tourism during the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s. Rapid growth and the possibility of large profits sustained an urban model based on non-compliance with the standards defined by the Land Act of 1956 (Ley del Suelo). The legacy of this phase was a dense and non-contiguous urban form that, as Leontidou (1990) has pointed out, represents a characteristic feature of the urban transition in Mediterranean Europe.

The study period begins with Spain’s transition to democracy, culminating in 1979 with the transfer of responsibility for spatial planning to the historical regions (the Basque Country and Catalonia) and the establishment of democratic town councils. The government also initiated a review of municipal planning, the aim of which was to improve the urban environment and remedy the errors of the previous period. However, as it turned out, the rate of urban development activity declined during this period because of the simultaneous onset of a recession.

The restructuring of the production system and Spain’s entry into the European Union (EU) in 1986 marked the beginning of a new growth cycle based on the tertiary sector and real estate. This stimulated the so-called “housing bubble” (Naredo and Montiel, 2011), one of the most distinctive aspects of the Spanish urban model in the context of globalization. Its causes were specialization in residential tourism, the reduction in the number of persons per household and the middle-class attitude to housing as an investment. Despite successive increases in prices, demand was sustained thanks to easily acquired mortgages, and an ample supply of housing was guaranteed because of the close relationship between the financial sector and large real estate companies.

Planning policy also facilitated this irresponsible dynamic. Local authorities competed to increase the supply of land and attract potential investors, and in many cases, this was their main source of income. In addition, regional administrations, including that in Catalonia, failed to implement regional land planning instruments (Esteban, 2003; Burriel, 2008). The inevitable result, given the improvements in road infrastructure and the potential earnings from development projects, was an expansion in the urbanized area and a lack of co-ordinated planning.

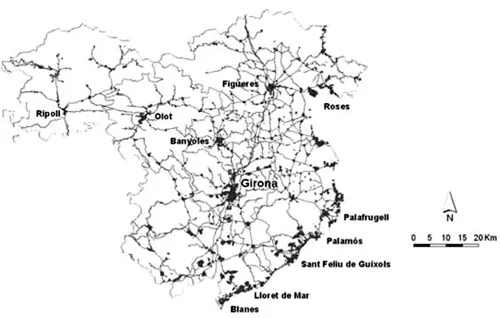

Figure 1.1 The Girona districts

Thus, in its Spanish version, urban sprawl – the phenomenon of dispersion, reduction in density and separation of uses in the advanced capitalist city (Bruegmann, 2006; Couch, et al., 2007; Indovina, 2009) – was an expression of particular factors related to planning and the economic and social structure (see Muñoz, 2004; Font, et al., 2004). Various international authors have also shown that the newly global urban form has displayed new morphological categories, portraying both the changing location patterns of economic activities and residence in the post-industrial city as well as traces of post-modern culture (Knox, 1991; Gospodini, 2006; Phelps, et al., 2006). The case study of the Girona districts provides an illustration of these themes.

The Case of the Girona Districts (1979–2006)

The Girona districts is one of the seven planning regions in Catalonia. This is an area of 5,500 km2 and 700,000 inhabitants organized around Girona, a medium-sized city of 150,000 inhabitants, which itself is the focus of a system of smaller urban areas (Figueres, Olot, Banyoles) and a group of coastal tourist municipalities (Blanes-Lloret de Mar, Palafrugell, Roses). This network is closely linked to the metropolitan region of Barcelona (MRB), an urban area of international status with nearly 5 million people (see Figure 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Girona districts settlement system

The Planning Scenario

In 1979, after the Generalitat (the regional government) had assumed responsibility for urban planning, the main municipalities of the Girona districts began to revise their local development frameworks. These new frameworks projected future scenarios for a period of 15 to 20 years.

The first local development frameworks prepared during this phase set out to moderate growth, repair the urban fabric and resolve the deficiencies inherited from the previous period. In this context, the concept of the zone development plan emerged as the basic tool used to define the morphology of urban areas in detail while also designating public space and facilities. However, in practical terms there were problems, partly because huge pockets of developable land and numerous illegal activities had to be incorporated into the new development schemes (for example, Lloret de Mar, 706 ha.or Vidreres, 613 ha.). Furthermore, the new supra-municipal planning schemes for urban areas (such as those for Girona and Figueres) rapidly broke down after the regional elections in 1980, as the new centre-right government believed that planning was entirely a municipal responsibility.

As a result, individual municipalities begin to formulate plans according to their own aspirations, and by the year 2000, many of these were grossly inflated. For example, in the case of one third of the local development frameworks for the urban area of Girona and the coastal municipalities, the area specified for urban development equalled or exceeded the existing built-up area of the settlement. Moreover, in many cases, development schemes were prepared from scratch during the 1990s, and therefore these limitations were not simply a legacy from the previous period. Despite the new planning regime, inertia effects combined with irresponsible management in some cases turned new planning schemes into nothing more than a blueprint for expansion and growth. Moreover, while core towns tended to appear well designed in terms of urban morphology and facilities, smaller municipalities competed with one another and their ambitious development plans merely encouraged a further wave of urban sprawl.

The Urbanization Model

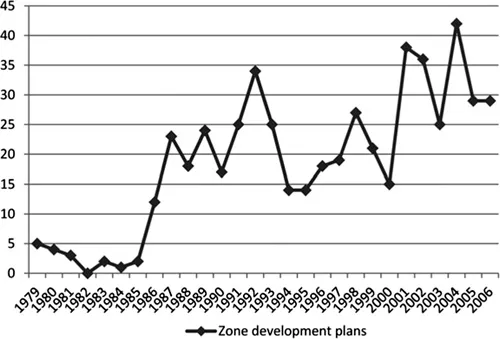

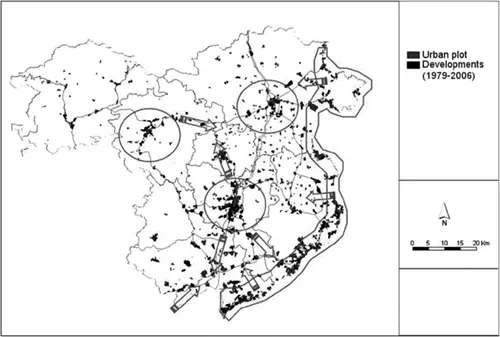

Between 1979 and 2006 inclusive, 522 Zone Development Plans were approved in the Girona districts involving 5,930 ha. (Figure 1.3). Newly formulated plans accounted for 70% of the area scheduled for development while the remaining 30% related to illegal projects dating from the period of desarrollismo that subsequently were regularized.

Figure 1.3 Zone development plans approved, 1979–2006

Source: Catalan Government.

The period can be divided into four phases. The first extended from 1979 to 1985 and was associated with the recession of the 1970s. The second phase extended from 1986 to 1992. This was a period of rapid growth accompanied by an influx of capital investment, stimulated by Spain’s entry into the EU. From 1992 to 1995, there was a brief recession, dealt with by devaluation of the currency, greater flexibility in the labour market and deregulation of the economy. The final phase saw a second cycle of expansion begun in 1996 and extending, with little change, until 2006. This cycle of expansion was even stronger than the first in terms of the Zone Development Plans approved (54%) and its duration (more than ten years). The spatial distribution of the Zone Development Plans can be seen in Figure 1.4.

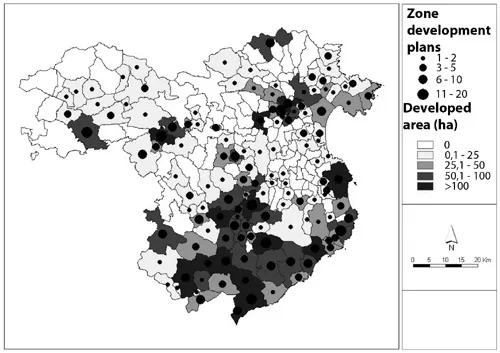

Figure 1.4 Spatial distribution of zone development plans approved, 1979–2009

Source: Catalan Government.

In tracing the proliferation of zone development plans, three spatial categories can be identified. Firstly the coast, which experienced high growth linked to the transition from traditional tourism (Fordist model) to residential property tourism. This process also affected the coastal hinterland (the line of municipalities further inland from the coast) for the first time. Secondly, the urban areas, where development involved not only core towns but more especially nearby municipalities in the surrounding areas: in the case of the Girona urban area, for example, only 24% of the plans related to the core town itself. Thirdly, the “network areas”, namely the municipalities located on the road corridors linking Girona with other urban areas, with the coast and with the Barcelona Metropolitan Region, in which new linear developments and centres emerged, unrelated to the traditional pattern of central places. Although overall there was significant growth in towns, the most striking aspect of this phase was the wide spread of urbanization throughout the Girona districts.

Sprawl was defined broadly to include not only physical dispersion (new developments characterized by a lack of physical continuity) but also oversized irrational extensions that doubled or even tripled the already urbanized land in a given municipality. According to these criteria, 40% of all zone development plans involved sprawl and these accounted for 60% of the total area covered by zone development plans. Half of this area related to subsequently regularized plans from the previous period, while half, unfortunately, related to new plans.

The problem particularly affected small municipalities on the coastline, second-tier coastal municipalities and those adjoining larger urban areas where sprawl was linked to oversized local development frameworks or “a la carte” revisions and “on demand” modifications of these. In these cases, developers moved to the hinterland, where they found not only cheaper rural land but also local administrations that were more likely to allow rezoning. After local municipalities had given preliminary approval to zone development plans, prospective developers, local governments and even unions then lobbied the provincial planning commission (the body whose role was to monitor local planning on behalf of the Catalan regional government) in order to win support for the plan. If the planning commission made a favourable report, final approval of the plan would then be given by the municipality. This led to confusion between public and private interests and enabled the private sector to make huge profits. In short, urban sprawl in many cases was the result of “free-riding” land use practices by urban developers with the consent of local administrations and in the absence of a coordinated approach to land use planning. Only the intervention of environmental groups prevented certain projects from coming to fruition (for example, the plans for Castell and Pinya Rosa beaches).

The Morphological Typology

Detailed examination of zone development plans indicated that urban sprawl in the Girona districts involved three distinct morphological categories: urban extensions, low-density housing estates and industrial parks.

Figure 1.5 Urban extension areas, 1979–2006

Source: Catalan Government.

The first category is urban extension. 236 zone development plans of this kind were approved, representing 46% of all plans and 26% of the total area. Urban extensions are compact housing estates with medium-high densities (the average is 34 housing units/ha). The concept of a compact, regular layout divided into blocks with buildings aligned along the street dates back to the pioneering work of Ildefonso Cerdà and his urban extension for Barcelona, developed in the second half of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century. Following Spain’s transition to democracy, this model was adopted with little modification and became the quintessential template for modelling urban morphology and growth in public space. This model led to the creation of new urban environments with mixed commercial and public spaces (plazas, avenues and facilities) and, from a social perspective, the relatively high residential densities (see Figure 1.6) fostered good community relations. From an environmental perspective, the per capita level of land consumption was low and the development of compact urban environments facilitated travel over short distances. Moreover, in its essential characteristics (compactness, low density and the mix of uses and social groups) urban extension embodied a high degree of continuity with the traditional Mediterranean city model.

Figure 1.6 Urban extension (Sarrià de Ter-Girona)

Source: Author.

The second category is the low-density housing estate (103 plans of this kind were approved, that is, 19% of all plans and 39% of the total area). Low-density housing estates consist mainly of detached houses distributed in a dispersed form. In Spain, this model has a dual historical root. On the one hand, as has often been pointed out, this reflects the influence of the Anglo-Saxon suburban tradition, though it is also noteworthy that single-family housing has historically been the dominant model in rural areas of Catal...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Urban Transformations: Centres, Peripheries and Systems

- 1 The Anatomy of Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean Region: Case of the Girona Districts, 1979–2006

- 2 Urban Regeneration in Porto: Reflections on a Fragmented Sub-regional Space, without Institutional Powers and “Lost” between Central Government and Local Authorities

- 3 Consumption of Advanced Internet Services in Urban Areas: A Case Study of Madrid

- 4 Housing Market Dynamics in a Peripheral Region: The Atlantic Urban Axis in Galicia, Spain: 2001–2010

- 5 Viability of Flagship Projects as Models of Urban Regeneration: The Representation of Space through the Discourse of the Actors

- 6 Creativity Beyond Large Metropolitan Areas: Challenges for Intermediate Cities in a Globalized Economy

- 7 Is Pennine England becoming More Polycentric or More Centripetal? An Analysis of Commuting Flows in a Transforming Industrial Region, 1981–2001

- 8 Riots by a Growing Social Periphery? Interpreting the 2011 Urban Riots in England

- 9 In the Shadow of a Giant: Core-peripheral Contrasts in South East England

- 10 The Fehmarnbelt Tunnel: Regional Development Perspectives

- 11 Vertical Extension Processes and Urban Restructuring in Sydney, Australia

- 12 Inner-City Social Gentrification in Tokyo: The Problem of Childcare

- 13 Power Nodes: Downtowns in the Periphery? A Case Study, Toronto, Canada

- 14 Just “Dumb and Boring” or “Over”? Lifecycle-Trajectories, the Credit Crunch and the Challenge of Suburban Regeneration in the US

- 15 Urban Transformation for Sustainability and Social Justice in Urban Peripheries: New Forms of Urban Segregation in Post-apartheid Cities

- 16 Recent Morphological Trends in Metropolitan South Africa

- 17 Metropolitan Transformation and Polycentric Structure in Mexico City: Identification of Urban Sub-centres, 1989–2005

- 18 Delhi and its Peripheral Region: Perspectives on Settlement Growth

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Urban Transformations: Centres, Peripheries and Systems by Daniel P. O'Donoghue in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.