![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Pernille Rieker

Dialogue has become one of the new buzzwords in international politics today. Small states in particular are increasingly stressing the importance of dialogue and mediation. For instance, Jonas Gahr Støre, former Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, has expressed a view that has become shared among many diplomats and scholars of foreign affairs: ‘… engaging in dialogue with a group and its members is not the same thing as legitimizing its goals and ideology. Used skilfully, engagement may moderate their policies and behaviour’. He refers to this approach as ‘principled realism’ – an approach that attempts to find solutions that both improve the world and recognize the constraints of the current global order (Støre 2011).

While there has been growing interest in the potential for dialogue as a tool for conflict resolution, it is still not clear what is really meant. The term is used in several different ways in the scholarly literature and the empirical discourse. ‘Dialogue’ is often used as a synonym for more formal negotiations between two or more parties in a conflict where the aim is to reach a negotiated agreement; further, it is commonly used to refer to the more informal processes (‘back-channel diplomacy’) of communication among opposing parties, leading up to such negotiations; and thirdly, the term is used quite extensively to describe the broader peacebuilding processes, grassroots initiatives, and bottom-up policy approaches that aim at avoiding the escalation of a conflict or crisis, but which rarely have an explicit ambition of reaching a concrete negotiation phase.

In addition to these diverse understandings, the role of dialogue also differs according to the context or the specific conflict in question. Of special importance here are factors like power relations and the existence and role of a third-party actor or facilitator. While these factors have been addressed in the literature on the potential and limits of negotiations (Jönsson 2005), few (if any) contributions have systematically explored the potential and limits of less formal dialogue processes. With this book, we aim precisely to fill that gap by focusing on such processes – those leading up to more formal negotiations, or the broader peacebuilding processes. All these informal processes hail dialogue as a progressive force in fostering mutual understanding and resolving conflicts. It is therefore central to the rhetorical vocabulary of foreign-policy actors. But, we ask: can dialogue carry such a burden? Does dialogue really resolve conflicts? And, if so, – under what circumstances and conditions?

This book critically assesses the role of dialogue as a political tool for solving deep-rooted conflicts among states and between conflicting parties within formally recognized territorial borders. Our ultimate objective is policy-oriented: to contribute to a more nuanced and better understanding of the potential and limits for dialogue as a tool for conflict resolution in deep-rooted conflicts and crises.

Dialogue in Deep-rooted Conflicts

Establishing dialogue between parties that may not be interested in talking with each other – and where a breakdown in communication is part of the problem, owing in no small part to conflicts over fundamental values – presents particular challenges.

The quality of any form of communication hinges on the context of communication and on the ability of the parties to present their message in a manner that is understandable – in other words, that messages can be coded and de-coded to avoid misunderstandings. Central here is how the parties to a conflict define the cause of a conflict and possible ways of addressing it. As we shall see, what is often lacking is precisely such a shared framework within which the causes of a dispute can be assessed and discussed. Instead, the actors create mutually exclusive causal narratives and deep emotions that serve to drive the parties further apart. For the sake of analytical precision we have chosen to focus on dialogue in case generally seen as ‘hard’ ones: high-intensity international conflicts, or crises with high stakes. We define a ‘crisis’ as a set of interlinked events where i) there is uncertainty on the part of actors about how best to advance their interests; ii) there are clashing values and interests, with high stakes involved; and iii) the actors are unsure about the facts of the situation and about the strategies of the other actors.

On this basis, we decided to study the following cases: the Russo-Georgian conflict of 2008 and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict that started in 2013; the conflict(s) between Western powers and Libya under the Gaddafi regime; nuclear (back channel) diplomacy and the conflict between Iran and the Western powers over Iran’s nuclear programme; recent religious tensions in Egypt and attempts at interreligious dialogue; the attempts at dialogue between the Kabul regime and the Taliban in Afghanistan, as well as the dialogue between North and South in Sudan.

In each of these case studies we aim at answering three inter-related questions:

1. What was the character of the dialogue between the actors prior to, during, and after the ‘peak’ of the conflict/crisis?

2. To what extent has the dialogue been successful?

3. What determines whether the dialogue can succeed?

Studying the behaviour of states during times of crisis – in a situation of not only conflicting values but also uncertainty about intentions of the other – can offers a good vantage point from which to assess the strengths and weaknesses of dialogue as a foreign-policy tool.

The Different ‘Tracks’ of Diplomacy

As hinted at above, we also need a better understanding and clarification of what is meant by ‘dialogue in international politics’. To be sure, the concepts of dialogue and negotiations are both essential elements of diplomacy. Dialogue seems to comprise the more informal communication between parties at different levels (at the political level and at the level of civil society). Negotiations and bargaining, on the other hand, generally refer to a more formal process initiated between two parties (often states), aimed at reaching an agreement or negotiated settlement.

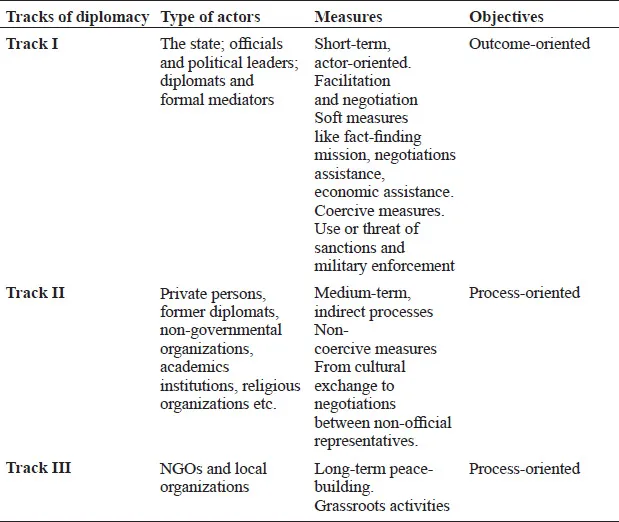

This means that dialogue may be referred to as both ‘Track I’ and ‘Track II’ diplomacy. These terms were first coined by William D. Davidson and Joseph V. Montville in their article entitled ‘Foreign Policy According to Freud’, which appeared in Foreign Policy in 1981 (Davidson and Montville 1981). According to these authors, Track I diplomacy is what diplomats do in terms of formal and informal (back-channel) negotiations between nations; Track II diplomacy is a specific kind of informal diplomacy, in which non-officials (academic scholars, retired civil and military officials, public figures and social activists) engage in dialogue, with the aim of conflict resolution or confidence building. This kind of diplomacy is often applied in deep-rooted conflicts or crises where there is the risk of the conflict escalating out of control (Davidson and Montville 1981: 145).

More recently, a third category of diplomacy has been introduced: ‘Track III’, referring to be dialogue initiatives undertaken by local grassroots organizations or international development agencies and the like. With this has come a greater focus on more informal dialogue processes in the scholarly literature as well.

While Track I diplomacy involves diplomats and applies outcome-oriented approaches, Tracks II and III involves civil society and are more focused on the process of confidence building than concrete outcomes (Reimann 2004).

The distinctions between the three tracks are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The Three ‘Tracks’ of Diplomacy: Actors, Measures and Objectives

While these distinctions might be helpful for creating an overview, there are also some obvious limitations with such a categorization. In practice, diplomacy, dialogue and negotiations tend to be highly more complex processes that include more actors, measures and processes than shown by this simplification.

It is important to note that the robustness of dialogue – as a tool for conflict resolution – depends crucially on how it functions and shapes actors in different settings. Much hinges on whether dialogue aims to promote understanding, whether it aims to change actors’ identities and interests, or whether it (merely) seeks to avoid escalation and the use of violence. Moreover, the motivations for engaging in a dialogue can differ. In some cases actors may engage in dialogue for instrumental or tactical reasons with no commitment to peaceful resolution of the conflict. In other cases, the UN Security Council may have imposed dialogue on the parties, without their having sufficient commitment to achieve further confidence building or an agreement of some sort.

Dialogue Situations where the Aim and Motivations Differ

It is also important to note that the distinction between the two diplomatic ‘tracks’, mentioned above, is far from clear-cut in practice. In fact, some types of informal dialogue situations are often facilitated by diplomats; if such dialoguing proves successful, more formal negotiations are likely to follow. Thus, one interpretation of ‘dialogue’ sees it as the process leading up to more formal negotiations. In turn, that means that some of the literature on negotiations might be useful for studying this type of dialogue. Here we should note the distinction between distributive and integrative approaches (Zartman 1988). Whereas the distributive approaches are far from a dialogue situation in the sense that they praise a zero-sum view where the goal of negotiations involves claiming one’s share of a ‘fixed amount of pie’, integrative theories and strategies have more in common with dialogue: that they look for ways of creating value, or ‘expanding the pie’, so that there is more to share between parties as a result of negotiations (Alfredson and Cungu 2008: 15). Perhaps the best-known example of the integrative approach is the ‘Harvard Negotiation Project’ which builds on the work of Roger Fisher and William Ury. They frame negotiation as a three-phase process, where efficiency depends on how negotiators treat four essential elements: interests, people, options and criteria (Fisher and Ury 1981). These four elements have, in a later edition of the same book, been refashioned into seven elements or steps of negotiations (Fisher and Ury 1991).1

While the integrative approach is also a strategy for Track I diplomacy, we may assume that this phase often is preceded by a phase of a more informal dialogue or some kind of ‘back-channel dialogue’. There might also be cases where Track II diplomacy actually goes over into a new phase, which can be analysed as a form of integrative negotiation process. Thus, the borders between the different types of processes are not always so clear-cut; in some cases, we might usefully combine insights from the literature on diplomacy, negotiation and conflict resolution, for a better understanding of the potential and limits of dialogue as a tool for conflict resolution. In this book, Track I diplomacy is therefore also used to describe the ‘back-channel dialogue’ undertaken by diplomats.

Additionally, there are cases where dialogue has no ambitions of leading up to a negotiation phase, but is seen as a way of promoting understanding and trust. The aim of such a process is then rather to prevent a more violent conflict or to avoid the escalation of an existing conflict. These processes are often facilitated by one or several third parties, and are frequently conducted more or less clandestinely. As the chapter by Thune and Nome shows, this type of dialogue processes is complex: indeed, it could include the whole peacemaking apparatus aimed at creating confidence and trust among the parties at various levels of civil society. While Reimann (2004) and others would include this in the category of Track II and Track III diplomacy (depending on the actors involved) that is process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented, Nome and Thune are sceptical about using such general and all-embracing tags. They prefer to call this non-party conflict diplomacy. This approach differs in that it refers to ‘the attempts of a third party actor – a state, international organization, NGO or individual – to engage one or more contending parties in dialogue to find a peaceful solution to an armed conflict, without using coercion and with no direct interest in a specific outcome’ (p. 31). While Nome and Thune agree that this type of dialogue is process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented and emphasize the importance of the neutrality of the third-party actor, they are less concerned about distinguishing between the actors and referring to these processes as different ‘tracks’: ‘most mediation efforts are Track I and Track II at the same time; not separate initiatives or processes – one official and the other unofficial – but often purposely combined’ (p. 33). However, even if the different tracks of diplomacy are combined, it might still be useful to distinguish between outcome-oriented and process-oriented approaches, as well as the power relationship between the opposing parties (see below).

Dialogue and the Role of Power

Dialogue situations differ also with regard to the power constellations involved. A dialogue between more or less equal parties will have a very different dynamic than one where the power relation is asymmetrical. While the former type may have at least the theoretical possibility of ending up as a Habermasian ideal-situation of communicative action (Habermas 1981) even if this is difficult in deep-rooted conflict, this is highly unlikely in cases of asymmetrical power relations.

Either way, a successful dialogue process always implies some sort of willingness to learn and be persuaded by the force of the better argument. This means that ‘soft power’ or the power of attraction might be relevant here. Joseph Nye (2004) has identified three distinct types of power: hard, economic and soft. Whereas the first two seek to coerce or induce in order to obtain the behaviour desired from another actor, soft power involves ‘getting others to want the outcomes that you want’. Threats and force are the ‘currencies’ of hard power, and payments/sanctions of economic power, but ‘policies, values, culture and institutions’ are the currencies of soft power. While hard power entails the ability to force preferences on others, soft power ‘rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others’ which in turn requires good communication skills.

Thus, the foreign policy tool of dialogue seems to fit quite well with the concept of soft power. This is a tool that traditionally has been favoured by smaller states, and by larger actors with fewer hard-power resources (like the EU), but has also become increasingly accepted as a fruitful approach for more powerful actors (for example, the USA). On the other hand, it is more difficult to be convincing as a credible soft power when that actor also has considerable hard power and economic power.

Dialogue is somewhat of a paradox in world politics: while dialogue is a defining feature of diplomacy and is frequently called upon to ease tensions and avoid conflicts, it can also be seen as a sign of weakness, precisely because it implies the willingness to change one’s position and be persuaded by the arguments of the other side (Kagan 2008). Since this is a central characteristic of dialogue (although different types of dialogue focus on different kinds of instruments), it may be important for communication to be conducted in secrecy. This may help to make it easier for the parties to speak more freely and consider various different options or measures.

Is Dialogue Always a Good Thing?

‘Dialogue’ often has positive connotations. But is it always a good thing? Dialogue with counterparts from the same culture, where actors typically share a set of values that can enable communication and promote conflict resolution, can be difficult enough. Dialogue in the international realm, amidst conflicting value systems and with no overarching authority to sanction an agreement, is even more difficult. There is often a lack of trust, even outright suspicion, and frequently – as shown in the cases presented here – no real interest in reaching consensus. As Jennifer Mitzen has observed, commenting on Habermas’ theory of communicative action, ‘strangers might not see consensus as desirable; they might not recognize one another as capable of communicative consensus at all, much less be willing to listen and reflect on each other’s arguments’ (Mitzen 2005: 404). In addition, there are other dimensions that may either facilitate or constrain the dialogue situation. The following three dimensions are crucial to any type of dialogue: secrecy versus openness, domestic legitimacy, and emotions. These dimensions are discussed in greater detail in the three concept-oriented chapters in the first part of this volume.

Secrecy Versus Openness

Because dialogue implies a willingness to be pers...