- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Practice Learning in the Caring Professions

About this book

Dave Evans makes a convincing case that practice learning occupies a central role in the education and training of the caring professions. In doing so, he affirms the activities of many service agency staff involved in practice teaching and assessment and offers them clear models and illustrative examples to aid their development. He also explores ways in which practice learning and assessment can be effectively developed in academic settings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

1

The Importance of Practice Learning

The position of practice learning, it would seem, is reasonably well established in the e ‘ucation of the caring professions. Students expect a substantial proportion of their learning to take place in practice settings, certainly in the UK although not consistently throughout Europe and the rest of the world (Doel and Shardlow 1996; NOPT 1998). Regulatory bodies seek to ensure that practice settings of sufficient quantity and quality are available. The image of practice learning as one of the ‘twin pillars of professional education’ (Walker et al. 1995; Evans 1987a) reinforces this impression of substance.

However, for a number of conceptual and practical reasons, this position is far from assured. Conceptually, the learning which takes place in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) is often accorded greater prominence than that which occurs in practice placements, for reasons discussed below. Indeed, the first two directors of the Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work (CCETSW) are on record as conceiving the learning to take place primarily in an HEI and then ‘put into practice’ in the practice placement (Gardiner 1989). Practically, the problem of resourcing practice placements, particularly of releasing busy practitioners to supervise, teach and assess students, threatens to diminish the practice learning component of professional education. Early CCETSW drafts of revisions to the Diploma in Social Work in the mid-1990s speculated over the possibility of not having placements in the first of two years. Some social work education departments are now offering degrees without a practice component (Evans 1996).

This chapter, therefore, seeks to assert the important, perhaps central role, that practice learning plays in education for the caring professions, partly as a bulwark to prevent further erosion of practice learning in a climate of financial stringency but more proactively to persuade all those involved in professional education to place a high value on practice learning.

What is practice learning?

From the growing literature on practice learning in the caring professions, it is difficult to extract a clear and succinct understanding of the distinctive nature of practice learning. Much of the literature (Jarvis and Gibson 1985; Brooks and Sikes 1997; Bogo and Vayda 1987; Thompson et al. 1990) seeks to aid practitioners in taking on the mantle of teacher and assessor and hence, understandably, concentrates on the roles, responsibilities and tasks of practice teaching and assessing - ‘teacher’ or ‘teaching’ usually having prominence in the title. Where ‘learning’ features prominently in the title (Butler and Elliott 1986; ENB 1996) the nature of practice learning seems to be taken as self-evident. Shardlow and Doel, however, elevate learning above teaching in their title and furthermore provide a definition of ‘practice learning’: ‘This term is used to refer to the learning that occurs whilst a student is on placement... It refers to the context of learning in the practice agency* (1996: 5). For Shardlow and Doel, practice learning is thus defined by the setting in which it takes place. Whilst setting clearly has a major impact on the processes of learning, as will be discussed below, it is possible to delineate processes inherent in practice learning which are independent of setting.

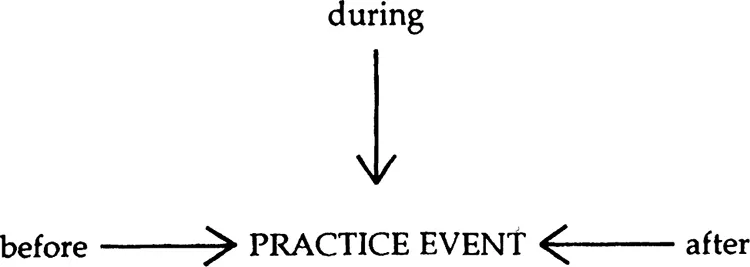

Practice learning essentially takes the specific practice event as the central source of learning. The phrase ‘practice event’ implies work not only directly with, but also indirectly on behalf of, the client, both of which are intended to ensure delivery of a service. It also includes the cognitive and feeling aspects of that work as well as the behavioural. Eraut (1994) uses the phrases ‘professional action’ and ‘professional performance’ to describe this event. The practice event is ‘central’ in three main ways. It is the principal source of stimulation to learn. It is also central in that the learning has a primary aim of improving practice and not merely of benefiting the learner in some other, vague way. It is this aim which requires an emphasis on supervision and accountability and not just teaching and learning (see Chapter 5). Finally, the practice event can be seen as chronologically central: learning can take place before the event as part of the process of planning, during the event as part of the process of adjusting the practice to a changing or unexpected context and after the event, particularly as part of reflection (see Figure 1.1).

In order that learning can focus centrally on the practice event, it is helpful if it is in close proximity to that event. The importance of temporal and spatial proximity is stressed in the literature (Eraut et al. 1995) and supports Shardlow and Doel’s (1996) emphasis on setting. However, there is also a need for conceptual proximity, whereby the thinking about the event is at some point reasonably concrete and is not constantly at a high level of abstraction.

Figure 1.1

Practice learning

Proximity in both practical and conceptual senses is clearly a continuum. At one end of the continuum, learning during a specific practice event which focuses on the practical delivery of an effective service is clearly practice learning. At the other end, learning which precedes any practice events by many weeks and is at a high level of abstraction with no reference to specific practice events is clearly not practice learning. The latter is a form of learning which takes place in many front-loaded professional education courses. In between these two extremes, it is possible, particularly on concurrent college/placement courses, for a teacher in an academic setting to facilitate learning from a recent specific practice event or for one that will shortly occur. Under such circumstances, I would suggest, practice learning can take place in a setting other than the practice agency.

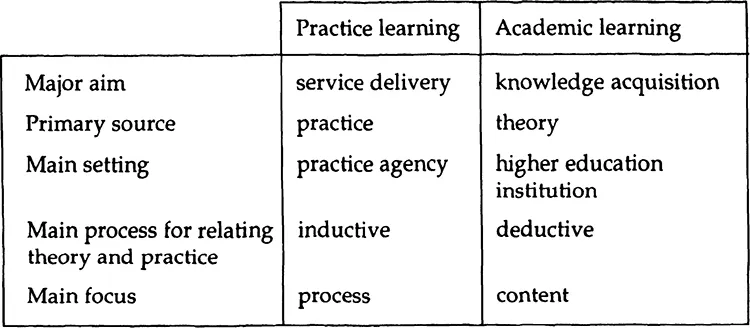

It is possible to contrast practice learning with academic learning - that is, learning designed to acquire theoretical knowledge and understanding (see Figure 1.2).

The different primary aims, sources and settings of practice and academic learning have already been discussed above. The two forms of learning are also differentiated in how they proceed to connect the primary source to a secondary source. Practice learning tends to move inductively from concrete practice to abstract theory while academic learning tends to move from abstract theory to concrete practice (see Chapter 4). However, it has to be said that the literature (Eraut et al. 1995) indicates how both practice and academic teachers are often reluctant to move away from their primary source of learning.

The final suggested criterion distinguishing between practice and academic learning is one of focus. Academic learning focuses mainly on the content of learning - the syllabus. In practice learning, the unpredictability of practice events renders the syllabus difficult to control, although the concept of ‘practice curriculum’ (Doel 1987; Phillipson et al. 1988) has sought to introduce a measure of control over the syllabus. Instead, the literature of practice learning seems to concentrate on key processes such as: the practice teaching session, the relationship between practice teacher and student and the support offered the student by agency staff. Gray and Gardiner (1989) make a similar distinction between content and process in their first two levels of learning.

Figure 1.2

Practice learning and academic learning

This comparison between practice and academic learning has developed a form of archetype for the two which inevitably oversimplifies and distorts what takes place in both practice and academic settings. There are some academic teachers, for example, who attend carefully to the processes of learning and rather neglect the content while there are practice teachers with the reverse priorities. None the less, the analysis is a definition by contrast and is offered in an attempt to elucidate a number of characteristics of practice learning, in addition to the one identified by Shardlow and Doel (1996).

The importance of practice learning: the evidence

Research evidence would also seem to support the view that practice learning has an important role in the education of the caring professions. A number of consumer studies of social work education undertaken in the late 1970s and 1980s (Shaw and Walton 1978; Davies 1984; Coulshed 1986; Faiers 1987; Davies and Wright 1989) all suggested that social work qualifying students tended to put more into practice placements and gain more from them than from college-based learning. It would seem that the only study of that period which discovered a more equal pattern of student satisfaction was of Ruskin College social work students, who the researchers acknowledged have a particular motivation towards ‘intellectual stimulation’ and ‘academic adventure’ (Bryant and Noble 1988). Social work educational studies in the 1990s seem to eliminate this contrast in settings from their research designs, despite major changes in both settings. None the less, two major studies in the UK (Walker et al. 1995; Marsh and Triseliotis 1996) and one in Australia (Fernandez 1998) still report a high level of student satisfaction (over 80 per cent) in their practice placements.

Research into nurse and teacher education, likewise, does not seem specifically to contrast learning in academic and practice settings. However, a similar pattern of high levels of student satisfaction seems to emerge. Macleod Clark et al. (1996) report that a few months after qualifying from Project 2000 courses, nursing ex-students cited clinical placements as the single most influential aspect of their course. This seems consistent with their finding that during the second part of students’ training, when more time is spent in the practice setting, students were finding mentors in the practice setting more influential in their understanding of nursing than academic teachers. Phillips et al. conclude similarly from their study of three and four-year nursing degree courses: ‘Quality in clinical learning is central to the whole strategy of professional development’ (1996: 79).

Following a review of two major studies of initial teacher education, Tomlinson (1989) advocates the value of an emphasis on the practice setting for student learning. Back and Booth (1992) surveyed opinions of both students and school teachers about practice teaching (’mentoring’) and presented a generally enthusiastic response. Hill (1997a) compares the responses of articled teachers, whose training was predominantly in the school, with those of students who were trained predominantly in a higher education institution. Whilst the pattern of satisfaction with their education and training is mixed, one of the most conclusive findings was a considerably greater satisfaction on the part of the articled teachers with the emphasis on practice teaching and learning (’teaching practice’) in their education.

These studies confirm an appreciation, particularly by students, of the major role learning in the practice setting plays in the education of a number of caring professions. This is not to deny the important contribution of learning in the academic setting, which is examined somewhat below (see Chapters 3 and 4). Moreover, it is likely, as Becher (1994a) suggests, that some caring professions, such as medicine, will tend to place greater emphasis on the academic setting, partly because of the more substantial physical science component in their education and partly due to the restrictions on students’ practice caused by levels of risk. However, the academic institutions tend to be the leading partners in professional education and it is tempting for them to overplay the role of academic settings and underplay the role of practice settings in student learning. This overview seeks to redress such a tendency.

Towards a theory of practice learning

It is possible to identify a number of theoretical explanations for the key role that practice learning plays in students’ educational experience. Three of these are intrinsic to the students: the fact that they are adults, the distinctive learning styles of caring professionals and the motivation of caring professionals to learn. Three explanations, however, are more a product of the context within which practice learning typically takes place: the opportunity to observe professional role models, the involvement in a community of practice and the opportunity to learn within a developing relationship. Some of these, such as adult learning and learning style theory, are discussed in depth in the literature on practice learning (Jarvis and Gibson 1985; Thompson et al. 1990; Shardlow and Doel 1996), although usually with the aim of informing the roles and tasks of practice teachers, rather than explaining the importance of practice learning. Others, such as situated learning and social learning theory, have as yet had less impact on practice learning. In this section, I shall briefly outline the main features of each area of theory and indicate how it tends to reinforce the important role played by practice learning in the education of the caring professions

Adult learning

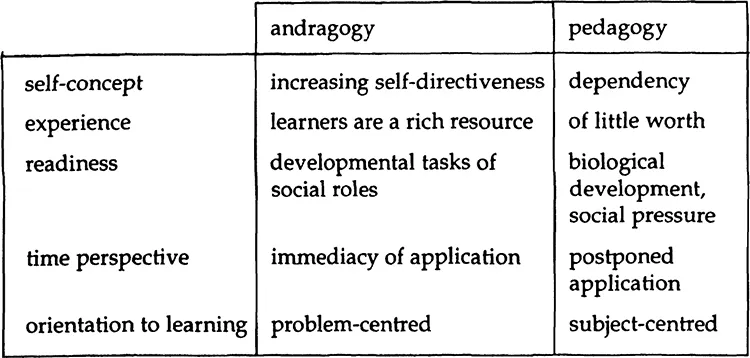

A number of writers (Knowles 1978; Cross 1981; Rogers 1983) have stressed that adults tend to differ from children in both their reasons for learning and also the ways in which they learn best. Whereas children learn as part of their biological development, adults need to have a particular purpose to encourage learning. Knowles contrasts the assumptions of adult learning, ‘andragogy’, with those of traditional ‘pedagogy’ in Figure 1.3 below.

Knowles (1978) also emphasises the importance of mutuality and negotiation in adult learning while Rogers (1983) stresses the importance of active involvement.

Whilst there have been creative attempts to develop the curriculum in academic settings according to andragogical principles (Burgess and Jackson experimentation 1990), there is a strong case that practice learning has inherently a greater orientation towards adult learning than much academic learning. Certainly, the centrality of the practice event gives an opportunity for active involvement and for the immediate application of learning to a specific task required as part of the professional role. Humphries (1988) usefully criticises the notion of mutuality in adult learning on the grounds of the real power differentials which exist between teacher and learner. None the less, it is likely that the student is more able to negotiate an educational experience which meets their learning needs in the one-to-one relationship of much practice learning than in the one-to-many context of much academic learning.

Figure 1.3

Andragogy and pedagogy (from Knowles 1978:110)

Figure 1.4

Kolb’s learning cycle

Learning style research

Learning style theory recognises the different approaches which individuals can take towards learning. The literature suggests a range of different learning styles. Smith (1984), for example, outlines 17 inventories which seek to discover different aspects of individuals’ learning style. Two learning style theories (Kolb 1984; Witkin 1950) seem particularly relevant to the processes of practice learning.

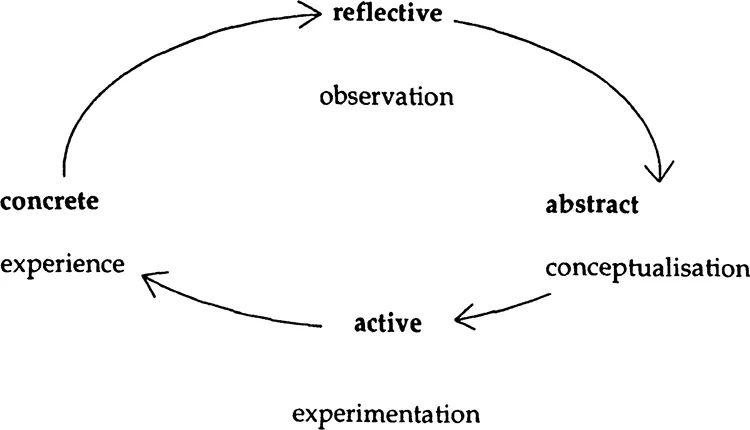

Kolb’s (1984) analysis of learning style is based upon a breakdown of the experiential learning process into four phases: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation. These four are based on two axes, concrete/abstract and reflective/active and are sequentially connected in a learning cycle (see Figure 1.4).

Four basic learning styles stem from different strengths within this learning cycle. Thus, the convergent learning style relies mainly on abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation; the divergent learning style relies on the opposite strengths of concrete experience and reflective observation; the assimilative learning style relies predominantly on abstract conceptualisation and reflective observation, and the accommodative learning style relies on concrete experience and active experimentation. Honey and Mumford (1995) use different terms to describe the same styles, respectively: pragmatist, reflector, theorist and activist.

Kolb and his associates (Kolb 1984) have undertaken studies suggesting that there is an association between learning style and professional career. The studies indicate that the professions as a whole have a more active rather than reflective orientation to learning. What Kolb terms ‘the social professions’, including nursing, social work, teaching, occupational therapy and physiotherapy, seem to be orientated particularly towards an accommodative style of learning: ‘The greatest strength of this orientation lies in doing things, in carrying out plans and tasks and getting involved in new experiences’ (1984: 78).

It is not clear from Kolb’s analysis whether the choice of profession shapes the learning style, the learning style shapes the choice of profession or both stem from more fundamental factors, although he seems to assert the former. Whichever is the case, it is probable that students of the caring professions share similar characteristics to their qualified colleagues. This is certainly supported by a small study of social work students in the UK (Bradbury 1984). Cavanagh et al. (1995) in a rather larger study of nursing students in the UK also found a dominant focus on learning from concrete experience, with a slightly increased frequency for the divergent style. Practice learning is, therefore, likely to have much to offer students in these professions, which academic learning may not.

Witkin (1950) proposes an alternative analysis of learning style based upon the one dimension of what he calls ‘field-dependency’. People with a field-independent style of learning tend to perceive elements independent of their context, to be analytical, whereas field-dependent learners see situations as a whole, with individual elements in context. Tennant (1997) suggests a number of associations with a field-dependent s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- In Memoriam

- Foreword

- Introduction

- PART I Part I

- PART II Learning in the Practice Setting

- PART III Practice teaching

- PART IV Part IV

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Practice Learning in the Caring Professions by Dave Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.