![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Resistance and Empowerment in Black Women’s Hair Styling is an invitation to an honest conversation on Black women’s hair styling. This conversation encompasses sexuality, standards of beauty, and options of choices in hairstyling through the voices and images of Black women: Because, at the end of the day, you’ve got to do something with your hair. Even doing nothing, is doing something!

This book seeks to analyze Black women’s hair as text. This interdisciplinary study focuses on hair culture through key cultural theories (Critical Race, Symbolic Convergence, and Social/Group Identity); semiotics and coded messages; and the economic, cultural and political significance of being a consumer of ethnic hair care products.

Hair culture for Black women across the Diaspora involves values, ideas, customs, and a system of representation. My study examines practices of hair adornment, including alterations of hair structure (straightening) with the use of chemicals, the role and impact of media in the conscious manipulation of choices regarding hair, and interpretations of aforementioned theories on womanhood as they apply to hair culture. In addition, the study seeks to ground its analysis in a careful assessment of what society reads into hair as a visible sign of convention or the breaking thereof.

Some may ask what messages does the Black woman send about herself and her consciousness by the hairstyle she chooses? Because hair is an ethnic signifier, the choice of a natural1 hairstyle can be read by the dominant culture as a troublesome sign. This is due, in part, to learned messages from dominant culture and consequently, Black women choose to “spend more time, more effort, and more of their income on their hair” than other populations (Britt 2000). Writer and lecturer of Black Diasporic Studies, Kobena Mercer explains such messages by saying, “Distinctions of aesthetic value, ‘beautiful/ugly’, have always been central to the way racism divides the world binary opposition in its adjudication of human worth” (Mercer 1994).

Why study Black women’s hair? My decision to look exclusively at this group, omitting Black youth or males who have their hair straightened, is based on a number of considerations. First, while Black youth and men must undoubtedly work to achieve hairstyles to their liking, derision is most dramatic for females, and Black women experience the most pressure to conform to White standards of beauty (Craig 2002). It is also a topic seldom addressed that provides understanding of race, identity, pride, and power. One benefit of this study is to promote better understanding of the politics of difference and how the “othering” of Black women has affected their sense of agency, entitlement, and critical thinking (Jhally 1997).

Second, the disproportional marketing of chemical relaxers and purchasing of hair-care products by Black women have strong connections to dominant cultural standards of an acceptable White look. What many Black women most often unconsciously admire is not the assumed physical beauty of White women, but rather the benefits that have accrued to them by virtue of their social and racial status (Jordan and Weedon 1995). Ingrid Banks saw the importance of investigating the “homogenized look” by interviewing 61 Black women and asking four questions. One of the questions was, “How does hair shape Black women’s ideas about race, gender, and beauty culture?” (Banks 2000). I consider this question important because consciousness of body choices and expression are the foundation of understanding autonomy in one’s choices. For the purpose of this book, I define an autonomous hair choice for Black women as an honest, self-directed choice grounded in understanding the historical causes and effects of Black women’s hair being political. Seldom are Black women allowed to make autonomous choices in hairstyles.

This unique dilemma makes hair political for Black women. For example, Inger Bostick, a Black female Clerk of Court in Savannah, Georgia, faced suspension from her job for wearing her hair in twists.2 A dress policy for Savannah Courts deemed twists unprofessional. Unfortunately, Bostick and many other Black women who desire to wear their hair in a natural state, in dreadlocks, braids, twists, and Afros, are informed by dominant White cultural norms, traditions, advertising, and employment dress codes that such looks are wrong, bad, and unacceptable. This dress policy may appear race-neutral on the surface, but its implementation entails racial discrimination – making culturally-specific hairstyles “unprofessional”. I see a political relevance of Black identity in the acceptance and/or disapproval of hairstyles worn by adult Black women.

This research will also demonstrate how Black women’s hair has been a site of resistance and cultural controversy that engages economic, social, and most important, political issues. And finally, this works examines the marketing of Black hair products to Hispanic/Latina and Bi-Racial women. Again, this plays into the lack of autonomy without backlash.

Beauty shops in Black communities are viewed as gathering places, not only to get one’s hair styled and groomed, but also to philosophize about various issues pertinent to Black women and hopefully serve as a springboard for autonomous hairstyle choice. Additionally, these beauty shops served an important social and economic function in the construction of Black communities between the Great Migration and the Great Depression (Silverman 2000). For example, in the 1920s, there were 108 beauty shops in Harlem, three times as many beauty salons as any other part of New York (Simon 2000). Even recently, the number of West African braiding shops and beauticians has increased. Many of these women from Senegal, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and other countries find braiding hair a means of employment that does not require a mastering of the English language, customs, or dress codes. This book looks at the symbolic space for agency that the beauty salon has served and continues to serve for Black women across the Diaspora.

Having looked at the social origins, development of beauty culture, and standards of hairstyles for Black women, one can conclude that race, class, and gender inequalities are key factors in choices of hairstyling. Beauticians, advertisers, entertainers, and others involved in the beauty industry play a role in suggesting how Black women should style their hair. Standards of beauty in dominant American culture do not always coincide with choices of Black women’s beauty standards and this is, in part, due to economic factors in maintaining certain hairstyles. There are connections between Black beauty, racial identity, and Black consciousness. Finally, corporate America attempts to exclude expression of racial identity that is non-Eurocentric, as a means of purporting a criterion set by dominant society.

My hope in researching and writing on this topic is that readers will see these hair dilemmas and understand the connection of group identity in resisting those who oppose their conscious choices of styling/grooming their hair. This is important because these decisions have intersectionality for Black women’s identity. In addition, this book seeks to provide readers with a stronger understanding of hair semiotics among Black women and what impact – positive and/or negative – the politics of Black beauty has on race, class, and gender inequalities.

Thus, my hypothesis is – American society reads Black women’s hair as text, historically and currently, to reveal that hairstyles speak for their self-identity. Black women’s hairstyles become signs of values. Unfortunately, some of these values of nontraditional hairstyles clash with the rules for appropriate hairstyles that govern most businesses and corporations in the United States. In trying to understand these problems, a few questions arise: (1) Are the politics of appearance (specifically with regards to hair) salient for all women?; (2) If so, why are Black women denied aesthetic approval and ascribed “unprofessional” status when they groom their hair in natural or “non-White” styles?; (3) Why do Blacks outspend Whites three to one on the beauty-product dollar?; and (4)What messages are seen in hair advertisements regarding Black women’s hair?

Two research methods are employed: the historical review of Black women’s hair and a content analysis of hair care manufacturers that advertised in Essence and Ebony magazines from 1985 to 2010. Historical review of Black hair advertisements will be empirical data. These media sell Blacks something else besides consumer goods, and that is the selling of an identity based on meeting dominant cultural standards of beauty. Additional sources are enslavement narratives and runaway enslavement notices discussing Black women and their hair. By looking at enslavement narratives, viewers can see how enslaved women saw themselves and what caused this view. This study, covering over two centuries, will connect the over-arching themes of Black women’s hair and how it is viewed over time.

This book develops the argument that one way in which Black women define themselves and one-another is by the way they style/groom their hair. As a result, hair becomes a physical manifestation of self-identity, revealing a private and personal mindset. Though there may be many personal reasons for Black women to choose to style their hair in a certain fashion, problems do occur when Black women do not comply with a “professional-look” often associated with European straight hairstyles. For example, a problem of being denied aesthetic approval when Black women style their hair in natural, braided, or “non-White” styles, ultimately hampers any hope of an independent choice for Black women. While acknowledging that White women have choices in the hairstyles they choose, what makes their situation different is, seldom are their hairstyle choices labeled “unprofessional”. Black female hairstyles are labeled as “unprofessional” when they give homage to ancestral heritage and/or do not meet expectations of the dominant cultural standards.

Three theories, Critical Race, Symbolic Convergence, and Social/Group Identity provide theoretical guidance to explore the relationship between two conflicting discourses; one, an inscription of race, the other focused on gender. Richard Delgado and Jean Stefanic explain that Critical Race theory seeks to investigate the transforming process of the relationships among race, racism, and power through economics, history, context, feelings, group and self-interest, and unconscious interests. Critical Race theory is being used to help understand that the discriminatory practices of reading natural hairstyles of Black women by dominant society is tied to, but not always protected under, federal employment practices. The ultimate goal is to use this discussion to spread awareness on hair aesthetics for the purpose of transforming this knowledge for the better. Many Critical Race theorists, such as Kimberly Crenshaw, are pigeonholed into being nationalists or essentialists or liberalists. While I do not feel these labels adequately reflect my position, I self-identify as a radical exceptionalist with regards to hair aesthetics because no other group of folk3 have experienced the continued degradation with regard to the grooming of their hair as Blacks.

From the Critical Race theory point of view, rights of hair grooming choices are imprecise and therefore can be interpreted in ways that serve to reinforce existing social hierarchies. This book serves as an appeal to a well-ordered moral universe, to end solid conception of appropriate behavior which shuns rational reflection, and which is shared by both speaker and listener. Because I address semiotic messages connected with hair grooming, I contend that Black women send messages by their hair styling choices, thus making them the speaker. They speak through the grooming options that they choose for their hair sometimes through compliance or the resistance of dominant standards of beauty. This book seeks to employ Critical Race, Symbolic Convergence, and Social/Group Identity theories understanding of how Black women, based on their race and gender, are objectified and why this oppression must stop.

Symbolic Convergence theory focuses on the way communication takes place in small groups in and this case for meeting an aesthetic appeal. Ernest Bormann,4 often noted as the creator of Symbolic Convergence theory, defines the theory as explaining how a group consciousness (shared emotions, motives, and meanings) is imparted through narrations or fantasies; the fantasies are the creative means that a group communicates their past and rationale(s) for the future with hopes of gaining solidarity from other groups (Bormann1985, 128). My reasoning for including this theory is to explain how the discussions of natural hair adornment have evolved with the use of media (e.g. Nollywood films) and technology (i.e. blogs and social networking sites). This need for cohesion, I will argue, is part of the desire to have a true autonomous hairstyling choice. I am curious about the content of these mediums ability to shape political choices of the consumers.

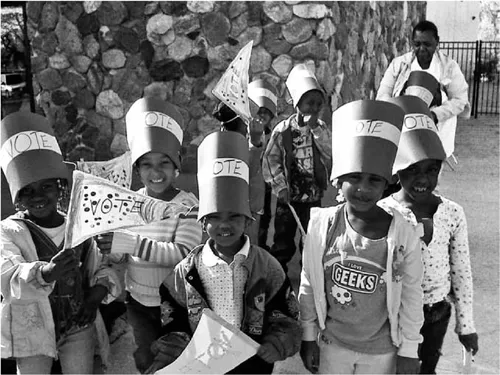

Social Identity theory has a history from the 1970s with theorist Henry Tajfel, but has been modified by other theorists to better understand intergroup behavior, attitudes, and beliefs. For the purpose of this book, Social Identity theory explains how women fit into groups, as opposed to where they fit in based on hairstyling decisions. Social Identity theory has a correlation to one’s categorization of a group, so throughout this book Social Identity theory and Group Identity theory will be used interchangeably. When proposing how Social Identity theory impacts one’s desire to “fit-in”, reader will better understand how consumer culture can influence one’s ability to link/form connections as an individual in a group. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1, where the day care students are adorned with flags and hats labeled “vote”.

These youths socially identify as a group because of the similar attire and message of encouraging observers to vote. Had one of the youth removed their hat or failed to wave their flag, their position in the group would have been altered. Therefore how they are positioned in the group is tied to their compliance with the adornment of the voting message that sends semiotic cues to the adult observer on what actions they should take.

To explain semiotics, I will draw upon my readings of the following theorists who specifically write about advances in semiotics; Kobena Mercer and Thomas A. Sebok. Roland Barthes, “great elder” of semiotics theory, is also crucial in this study (Sebeok 1991). I seek to incorporate from my readings on semiotics, a literary criticism of a non-literary object – hair as text. Consequently, hair becomes a sign to be analyzed and, because hair can be coded as an aspect of appearance under voluntary control, how one interprets the hair is of great importance. In addition, I draw upon Stuart Hall’s theoretical principles of encoding and decoding messages, grounded in semiotics. Semiotics, for the purpose of this book, notes what signs about hair mean, how hair is signified and read, and what impact hair culture has on Black female consciousness. Semiotics can be of great practical use in dislodging the Eurocentric way of viewing Black women’s hair because such an investigation will challenge the status quo by revealing systematic pre-suppositions (Solomon 1988).

Figure 1.1 Day care students in Illinois on November 4, 2008

Literature

There are two areas of literature relevant to this study: Black history and hair simultaneously in a chronological fashion. To fully understand how a Black hairstyle is to be read requires an understanding of the individual and the historical and cultural context of Blacks in the United States. Hence, it is important to examine factors that contribute to the social, political, economic, legal and educational disenfranchisement of Black women (Jewell 1993). Many cultural historians have not recognized the significance of hairstyling, grooming, and aesthetic practices for Black women until recently. As I began to formulate my project, I was most greatly influenced by Noliwe Rooks, who explored the historical, political, and cultural elements of Black women’s hair from enslavement to the 1990s. Rooks’ review of Black history in Hair Raising: Beauty, Culture, and Black Women showed Blacks have been dominated by two competing pressures: (1) the attempt to erase Black consciousness and (2) the development of Black identity as it relates to hair. For me, this was the first time I had found a text that chronologically looked at Black women from enslavement to the present as an expression of self, while trying to please White norms of attractiveness.

Writings on enslaved culture proved valuable in understanding where the notion of “good” and “bad” hair started. Having a better comprehension of living conditions of enslaved individuals helped me know why “good hair” meant straight hair and why “bad hair” meant kinky. Nevertheless, the quest for good hair did not stop after enslavement. In the beginning of the 1900s, hair culturalists became popular encouraging Black women to use straightening combs to obtain “good hair”. Madam C.J. Walker, who had been trained by Annie M. Turnbo Pope Malone, was sending Black women the message of empowerment through “good hair” as well as job opportunities selling revolutionary hair care products and practices for that era. This was at a time when many Blacks were economically and politically disadvantaged. A great number of Blacks from 1900 to the 1930s opted into straightening their hair with straightening combs, in the hope that having their hai...