![]()

1

SETTING THE SCENE – BRONZE AND IRON AGES

Early Bronze Age – c.3600–c.2000 BC

Middle Bronze Age – c.2000–1600 BC

Late Bronze Age – c.1600–c.1200 BC

Iron Age – c.1200–c.539 BC

Persians – 539–333 BC

Aleppo must have one of the most mundane settings for a major city. Many travellers in the past have noted that it fails to announce itself. This was put in a characteristically blunt style by an Australian officer, Hector Dinning, at the end of 1918. He had been one of the celebrated Light Horsemen whose mounted charge at Beer Sheba the previous year had helped bring the collapse of Ottoman Arab empire. Sent north at the end of the war to join the British occupying forces in Syria, he noted:

It is undeniable that Aleppo lacks a defining context, stranded on a corner of the dusty north Syrian plain and too far from the highlands of eastern Anatolia to the north to benefit in terms of distinctive geographical features. It is only as you descend the bowl of low hills forming a perimeter that the striking profile of the great medieval Citadel rears, competing today with graceless skyscrapers in your line of sight but still commanding attention.

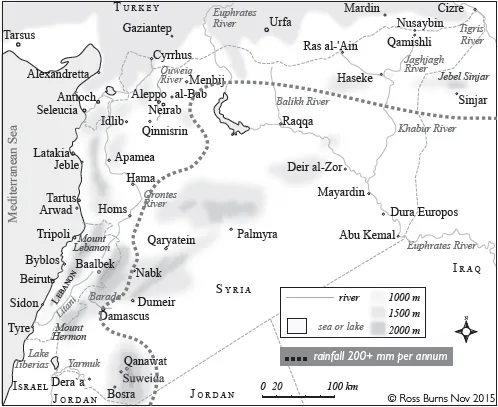

Aleppo’s only water resource was the Quweiq River, a small, 130 kilometre-long stream that flowed out of the hills around Aintab (modern Gaziantep) to the north in Turkey. The river fed a thin band of grain cultivation, orchards and kitchen gardens supplying just enough to attract settlement in an area otherwise deprived of water needed to supplement the low seasonal rainfall. Though the flood plain of agricultural land reached by the river widened as it flowed past Aleppo, the Quweiq could not in itself support a major population centre. What little the stream can muster today is siphoned off well before it reaches Aleppo, surviving only as a storm-water drain through a modern city park. Thirty or so kilometres south of Aleppo, the river gave up the struggle against the harsh reality of the Syrian steppe and evaporated in marshes to the south.2

Most major historic urban centres that survive through to modern times have an obvious asset that would have recommended them to their founders. The vigorous Barada River supplies Damascus with its snow-fed flow even during the summer months and sustains an extensive oasis in what would otherwise be desert. In the case of Antioch, 100 kilometres to the west near the Turkish coast, the city founded by one of Alexander the Great’s successors was fed by the waters of the Orontes. That river brought the inland run-off from the Lebanon and Syrian coastal mountains and bounced along with such enthusiasm that it earned itself in the past the Arabic nickname ‘the rebel’.

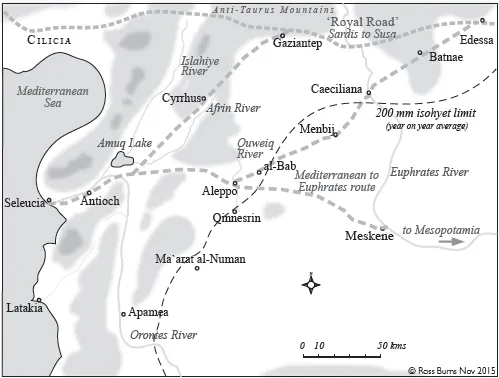

Stripped of the accumulated over-burden of more than five thousand years, it is hard to identify what Aleppo offered its first settlers. This corner of the steppe lies at around 400 metres above sea level. To the southeast, the land stretches for hundreds of kilometres towards the deserts of Arabia. To the north, the ground rises slowly until it meets the southern limit of the eastern Anatolian highlands and the Anti-Taurus Mountains. As the terrain reaches around 450 metres in elevation, it forms an ideal corridor bordering the foothills providing easy access from west to east, the historical route along which much of the contact between the civilisations of the Mediterranean and the great cultures of Mesopotamia and Iran flowed. It first passed into written records as the ‘Royal Road’ that bound the Persian Empire, linking its royal centre, Susa in modern-day Iran, as far west as the Aegean Sea. Aleppo, however, lies some way south of that corridor.

The easiest and shortest connection from the Mediterranean to the basin of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers is the inland road from Orontes mouth at Samandaǧ. Aleppo is less than 100 kilometres from the coast. After traversing Antioch (modern Antakya), the route heads inland through a convenient gap in the range of mountains that sweeps south from the Anti-Taurus Range petering out in the Sinai. Another 50 kilometres brings it to Aleppo and from there the shortest connection to the Euphrates lies across featureless, dry agricultural land. The Aleppo route provides virtually an open door to the great agricultural spread of the Land of Two Rivers or Mesopotamia.

If there is any advantage in Aleppo’s situation, it lies in its proximity to the point where the route inland from Antioch flexes northeast to join the corridor of the ancient Royal Road. Stretching from Sardis in western Anatolia, the Royal Road provided the great trunk route between the Aegean and Persia, notably in the Achaemenid and Hellenistic periods. On the other hand, if the traveller’s destination is Mesopotamia, landing at the port of Antioch (ancient Seleucia) and choosing the inland route via Aleppo allows easy passage across relatively flat country – by far the fastest way of reaching the next opportunity for water-borne traffic, the Euphrates. It is therefore not the immediate benefits of Aleppo’s topography but its access to two nearby key communication routes that have sustained the city’s historical role. As the long-distance trade in such key commodities required by ruling groups across the Fertile Crescent grew, Aleppo’s territory stood alongside a web of routes transferring precious metals, copper and wood especially to Mesopotamian markets deficient in these essentials. Even when at least the domestication of the camel in the early first millennium made the cross-desert route to the lower reaches of the Tigris-Euphrates viable, Aleppo still offered the greatest choice of access to long distance trade flows.

Environment

While Aleppo’s environs lack perennial streams, the city lies within the 200 isohyet rainfall zone, usually enough to ensure adequate grain supply and pasture across the flat open countryside. The stonier limestone country to its west and north is less favourable to broad-scale agriculture but can support grazing and the growing of olives and fruits on the slopes or in pockets of relatively rich soil trapped between rising country.

The climate of inland northern Syria is relatively harsh. Long cloudless summer months offer temperatures around 35–40 degrees with no rain. In winter, minimum temperatures often descend to just above freezing (occasionally diving to minus ten) and the city experiences a variable pattern of rain arriving in cloudbursts with occasional snow. The unequal distribution of rain throughout the year brings a reliance on adequate water storage. The run-off from the higher land to the north cannot be counted on for the rest of the year and subterranean capture is limited. The variety of crops grown is therefore limited to those that can avoid or endure the long rainless summers. More intensive zones of fertility can be found in the shallow valleys fed by streams, including the Quweiq, but they are often very seasonal in their flow. Even water for domestic use could be problematic. The city’s fresh water was supplemented by channels bringing water from the springs at Hilan in the hills to the north. This supply was delivered by aqueduct from the Roman period. Much of the water was then stored under the city in domestic cisterns, many of which survive to this day.

Besides grain (traditionally corn and wheat), fruits and nuts, Aleppo lies in country best suited to the raising of sheep and goats, usually grazing between seasonally productive agricultural areas. Aleppo largely learned about trading the hard way, through millennia of experience of buying in supplies and processing and trading products to surrounding markets, especially to the north. However, in periods of longer-term stability, Aleppo moved to a new level of prosperity. Its access to long-distance trade with regions far to the north, east and southeast, tapped markets ranging as far as Baghdad and Basra down the river system of the Tigris-Euphrates, Persia to the east and Asia Minor to the north and west.

A high place

If Aleppo had nothing much to offer to attract a permanent population of any size, what accident of history led to its steady rise to urban status and eventually to its rank as the most populous of the major cities of Syria? It had one small feature that other centres lacked: an elevated rocky outcrop on the edge of the steppe which could readily house an important defensive or religious centre. Prominent man-made mounds or tells dot the countryside of northern Syria, marking population centres that died out millennia ago leaving behind the accumulated detritus of their houses and contents. Aleppo’s central mound, today occupied by the magnificent Citadel of the Islamic Middle Ages, has long been a feature that defined the city’s profile and provided it with a major defensive asset.

Unlike the customary mound (or tell) left by layers of human occupation, Aleppo’s Citadel rise is a largely natural rock feature, though to some extent its features have been rounded off by the shaping of the material remains of many centuries. A medieval visitor from al-Andalus, Ibn Jubayr, marvelled at the claim that the rocky rise had its own natural spring that permanently assured a supply of water but it is more likely that the early inhabitants relied on two deep caverns serving as cisterns topped up by the winter rains.

If we look further at the terrain beneath the centre of the modern city, the reasons for its early rise to fame might become a little more apparent. Figure 1.3 shows the ground underneath the historic walled city of Aleppo and marks the perimeter of the historic walled area. For the moment we are concerned only with two underlying features. The first (marked on the right of Figure 1.3 below) is already apparent from historic engravings – the Citadel hill that rises to 437 metres above sea level (and thus almost 40 metres above the level of the plain). There is, however, a second elevated feature on the western side of the historic city centre, the Aqaba Quarter (in English, ‘the slope’). Not noticed by most visitors, this hill is lower, rising only some 20 metres above the city’s average.

This prominence lies on the northwestern edge of the area later defined by the ancient and medieval city grid which would fill the area between the Citadel hill and the Aqaba Quarter. Attention was drawn early last century to this area as the location of an early settlement. The presence of ...