Addictive behavior

A striking characteristic of addictive behavior is the pursuit of immediate reward at the expense of longer term deleterious outcomes. Moreover, addiction is typically accompanied by the expression of a strong desire to cease from or at least control consumption that has such consequences, followed by lapse, further resolution, relapse, and so on (Ainslie, 1992). Understood in this way, addiction is said to include not only substance abuse but also behavioral compulsions like excessive gambling or even uncontrollable shopping, which bring immediate short-lived rewards followed by the possibility of longer term aversive consequences (Müller and Mitchell, 2011; Ross et al., 2008, 2010). While profound preference reversal may not amount to a definition of addiction, its prevalence among addicts has led to the understanding that their behavior is explicable in terms of competing brain regions which in turn engender heightened saliency of immediate rewards and awareness of the longer term consequences of indulgence.

From another perspective, addiction has been described as a “disorder of choice,” as “voluntary behavior” (Heyman, 2009), albeit in Skinner’s (1953) sense of such behavior as that determined by its consequences in the process of operant learning rather than elicited by preceding stimuli as in classical or Pavlovian conditioning. Given Skinner’s argument that operant behavior is no less environmentally determined than that produced in classical or Pavlovian conditioning, Heymann’s use of the word “choice” is interesting. From the point of view of radical behaviorism, there is no suggestion that the behavior of the addict is chosen in the sense that it reflects free moral agency. Rather, the implication is that such behavior is the result not of a medical condition or underlying physiological susceptibility to the effects of ingested substances but of the contingencies of reinforcement and punishment within which it is embedded. Hence, if the response costs of obtaining and ingesting such substances increases sufficiently, the behavior will occur less frequently or even cease. Its consequences are its causes. More accurately, its rate of repetition is a function of the consequences which similar behavior has generated in similar circumstances in the past. This is the essence of operant explanation.

Intriguing as the debate about free will and determinism in the context of addiction may be, it raises but leaves unresolved the proper role of mental language in the description and understanding of addiction. Cognitive psychology is generally conceived of as a deterministic science but its practitioners have trafficked nonetheless in such intensional concepts as desires and beliefs, information processing and decision-making, which to the layperson imply at least a phenomenological level of understanding and often a sense of personal agency.

This book speaks of addiction as an extreme mode of consumer choice, different in degree though not in kind from more routine modes of consumption; that is, consisting in the use of products and services that serve as reinforcers, engendering similar neurophysiological responses and emotional rewards, but in the case of drug and process addictions generating also craving and compulsion that go well beyond the usual desire for more economic goods until the addict’s life is seriously disrupted (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 Compulsion and addiction

Compulsion implies an inability to control one’s behavior despite awareness of its deleterious consequences. Compulsive drug use has several causes: biological, both genetic predisposition and current physiological pressures; contextual, social pressures and substance availability (including classical and operant conditioning which determine the efficacy of environmental stimuli); and cognitive, beliefs that rationalize behavior (Altman et al., 1996). The view that all are implicated in drug addiction is insufficient for understanding and treating addiction which require a precise model of causal interaction (Carlson, 2010). Moreover, any attempt to differentiate among these sources of causation raises questions of free will and determinism which involve the nature of choice and invite consideration of the role of the alternative causes. In examining the role of neurobiology as the basis of compulsion, therefore, it becomes necessary to set this particular perspective within the context of the other influences on choice.

The first consideration of a biological perspective on addiction is why this phenomenon could have evolved through natural selection. Evolutionary logic suggests that the results of ingesting certain substances would have been adaptive and that the hedonic associations of such ingestion would have provided immediate reinforcement for the whole chain of behaviors that produced them (Panksepp, 1998). But the genetic structures preserved in this process play a limited role in influencing current behavior: while genes may specify the general adaptive goals of behaving by determining primary reinforcers, they do not determine specific behaviors or the secondary reinforcers that control their incidence (Rolls, 2005). Heritability measures apply to whole populations and have limited if any explanatory value for individual behavior (Joseph, 2003). It cannot be denied that genetic factors influence the etiology of addiction (Heyman, 2009, p. 93), since studies of fraternal and identical twins indicate that shared genes increase the probability that twins share drug dependency (Kendler et al., 2000; Tsuang et al., 1998, 2001), but their influence is far from straightforward.

Evolutionary considerations are, however, implicated in the ways in which brain systems register the current reinforcing/punishing consequences of drug ingestion and thus the likelihood of future drug use. Two examples are presented to illustrate the extensive role that biogenic factors play in addiction: the tendency of a drug such as cocaine to induce craving for its continued self-administration, and the role of the insula in evoking urges to use drugs based on representations of interoceptive phases of ingestion. Dopamine (DA) is associated with wanting or craving a drug rather than with the hedonic pleasure of taking it (Berridge and Robinson, 1995). This is especially apparent in the case of cocaine which interferes with the re-uptake of DA, permitting it to influence its receptors over time. The cocaine rush or high that is the result of this is thus prolonged and strengthened. The outcome is that the behavior of cocaine use which precedes such reinforcement is continually evoked, with the result that the individual experiences a craving for the drug (Hyman and Malenka, 2001).

The resulting focus of research has been on the mesolimbic dopaminergic system (Box 3.2) and other brain regions such as the amygdala and ventral striatum involved in emotional responses. But there is recent evidence that the insula is important because of its relation to the conscious craving for drugs (Naqvi and Bechara, 2008). This role has been revealed by correlation-based fMRI studies which show the increased activity of the insula during self-reported urges to ingest drugs. Such activity is related to the emergence of the secondary reinforcers which tie drug use to specific behavioral and contextual factors and to the cognitive drivers of drug use. “Over time, as addiction increases, stimuli within the environment that are associated with drug use become powerful incentives, initiating both automatic (i.e., implicit) motivational processes that drive ongoing drug use and relapse in addiction to conscious (i.e., explicit) feelings of urge to take drugs” (Naqvi and Bechara, 2008, p. 61). The ritualistic practices involved in the preparation of drugs, associated with specific places, apparatus, packages, lighters, and so on, thus become sources of the pleasure that reinforces not only those activities but the consummatory acts of drug ingestion. These processes, which elicit specific memories of encounters with the contexts and the drugs, are also responsible for differences in the subjective experience of urges for various drugs be they cigarettes, cocaine, or gambling. By ensuring that the individual keeps particular goals in mind, the insula is also involved in (thwarting) the executive functions that might overcome drug urges (cf. Tiffany, 1999). The learning process includes the development of neural plasticity through DA priming with respect to the impending chain of appetitive events; Naqvi and Bechara (2008) propose that this DA dependency invokes activity in the insula and associated regions such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and amygdala. The plasticity involves the establishment of representations of the interoceptive outcomes of using drugs and thus engender relapse even after long periods of non-use.

These neurobiological processes appear sufficient to account for compulsion, the indulgence in immediate pleasures in the knowledge that they will eventuate in severely unpleasant consequences. Behavior enacted in the face of impending contingent punishment which we have previously experienced and of which we are cognitively aware seems so irrational as to be explicable only in terms of chemical forces over which we have no immediate control. But reinforcement and punishment suggest an alternative explanation. Brain-based emotions, urgings and cravings, which are the ultimate rewards and motivators of behavior, are the endpoint of a sequence of behavior–environment relationships that make addiction controllable. Heyman (1998, 2009) points out that, whereas the biogenic influences which lead to the definition of addiction as a disease beyond the control of individuals, an alternative model is based on the existence of choice. The environmental contingencies that are the immediate regulators of operant responses control “voluntary” behavior that is selected by its consequences, rather than elicited by antecedent stimuli. This in turn gives rise to the idea of choice as behavior that is determined by its costs and benefits, and even by cognitive consideration of its costs and benefits. The import of Heyman’s proposal is that since operant behavior can be modified by the manipulation of its consequences, particularly by increasing the immediate costs of acquiring and taking drugs, it is under the control of the individual. This shift in the locus of control from internal chemistry to the person acting in a context of rewards and sanctions indicates, according to Heyman (2009), that addiction is not a disease but a choice.

Heyman is correct in raising the possibility of treating addiction by changing its consequences but it must be noted that he uses terms such as “voluntary” and “choice” in ways that are likely to mislead non-behaviorists. Skinner (1953, pp. 110–112) distinguished reflexive or “involuntary” behavior from that which is operant or “voluntary.” It is in this sense that behaviorists distinguish voluntary behavior, and Skinner was at pains to point out that “voluntary” behavior is as much under the control of environmental contingencies as “involuntary.” Heyman’s proposal seems disingenuous if he does not make explicit his understanding of the terminology of choice. His emphasis on the need to research environmental determinants of behavior and their interactions with biological functioning is nevertheless overdue.

This book applies a methodological approach to the explanation of consumption based on Intentional Behaviorism (Foxall, 2004, 2007a, 2007b, 2008, 2015c, 2015d) with the overall objective of understanding better both addiction and its explanation. Intentional Behaviorism is a methodology which incorporates the parsimonious model of behavior advanced by radical behaviorism in order to ascertain the point at which intentional interpretation, including cognitive narratives, becomes necessary to account for observed behavior. Hence, the method is not confined to the investigation of consumption via the extensional sciences. Rather, the objective is to learn from this process not only where intentional language and explanation are appropriate, and hence avoid their unnecessary proliferation but also to understand better the unique contribution to understanding that the parsimonious model, which avoids intentional idioms, can make.

This theme of addiction permits, above all, an opportunity to test and evaluate the theory of consumer choice. Most of the empirical research which has founded the model has been concerned with routine aspects of consumer choice such as product, brand, and store selection, and with the interpretation of relatively routine aspects of consumer behavior like spending and saving, the adoption and diffusion of innovations, environmental conservation, and the role of marketing management in shaping and maintaining patterns of consumer choice. My overriding aim is, therefore, to evaluate the model itself as a theory in terms of its applicability to the phenomenon of addiction. This investigation of addiction as consumer choice is not simply a case study for the testing of conclusions drawn elsewhere: it is part of an extension of the thinking inherent in the research program itself and its applicability to understanding human consumption.

The Consumer Behavior Analysis research program

When I began to study, teach, and undertake research in consumer behavior, there was a strong tendency to explain choice in cognitive terms and to do so somewhat uncritically on the understanding that any behavior was necessarily preceded by a mental attitude or intention. This assumption derived naturally from everyday folk psychology and was reinforced by the ascendancy of cognitive psychology at the very time when modern consumer behavior studies were coming to the fore. (Realization that a suitable framework of conceptualization and analysis for this purpose was Skinner’s radical behaviorism (1945, 1953) led to a critical examination of the epistemological basis of radical behaviorism in terms of its distinctive ontology and methodology and to an assessment of its role in the interpretation of consumer choice (Foxall, 2010b)).

The cognitive explanation of consumer choice has since then become more sophisticated but I believe there is still a need for the research program I inaugurated in order to reach more stable and reasoned conclusions about the nature of cognition and its role in social scientific explanation. The procedure of this program was to employ a behaviorist model of consumer choice, one which entirely eschewed cognitive and other intentional variables, and to ascertain how far one could go by using it to understand consumer choice. In this way, by testing the behaviorist model to destruction, it would be possible to ascertain the point at which behaviorist assumptions broke down, and the nature and role of the required cognitive variables would be revealed. At the same time, any positive contribution of the more parsimonious model would also become apparent. These expectations are being met and the results of the research program provide a foundation for continuing investigation.

Mindful of the behaviorist dictum that allusion to mental entities is unnecessary to explain observed behavior (Skinner, 1950, 1963, 1974), it becomes necessary to employ intentionality with care and consideration in order to generate a plausible and responsible psychological explanation of choice. It is here that the conceptualization of addiction as consumer behavior comes into its own, since the approach to consumer research with which I have been associated for some decades has been intimately concerned with the probity of a cognitive approach to the explanation of consumer choice.

The Behavioral Perspective Model (BPM; Foxall, 1990/2004, 2010a) is a means of exploring and explaining consumer choice in relationship to its environmental determinants. As the research program was designed to demonstrate, the application of this model to consumer choice has revealed both the advantages of a parsimonious approach to the explanation of certain aspects of consumer behavior and the bounds of behaviorism: the points at which an intentional or cognitive intentional interpretation of consumer behavior becomes necessary and the form it should take (Foxall, 2004, 2007a, 2008b). The opportunity has accordingly been taken to develop further models and methodologies which incorporate intentional interpretations (Foxall, 2007b, 2007c, 2013).

The methodology of Intentional Behaviorism

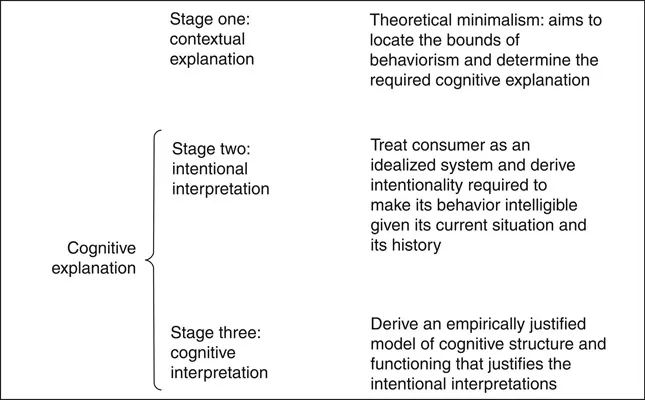

Figure 1.1 The sequence of Intentional Behaviorism.

The methodological procedure entailed in Intentional Behaviorism, which is described at greater length in Foxall (2016a), has three stages (Figure 1.1). Stage One, Theoretical Minimalism/Contextual Explanation, is marked by the use of extensional behavioral science in a spirit of theoretical minimalism to establish the bounds of behaviorism. At this stage, choice is conceived of as behavior in the context of alternative behaviors: the ratio of a person’s performance of behavior A as a proportion of his or her performances of all other behaviors: A:A′, for example, the number of times a consumer purchases a standard pack of a particular brand of breakfast cereal compared with the number of his or her similar purchases of other brands. The purposes of this stage are, first, to determine the extent to which a parsimonious, behaviorist model can account for aspects of consumer choice that are not revealed by other models; and second, to identify where an intentional account of behavior becomes necessary as a result of the inability of the extensional model to explain observed activities, and the form that that intentional account must take in order to interpret the behavior. Usually, this entails that the stimulus conditions necessary to predict and control the behavior are not empirically available. Three such bounds of behaviorism have been identified: in accounting for the continuity/discontinuity of behavior, in providing a personal level of exposition to interpret behavior, a...