![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Crisis and the Context

Carlos’s parents were worried. Immigrants to the United States, they had worked hard as a day laborer and a housekeeper to earn enough to buy a modest home in a not-so-good neighborhood that harbored several street gangs. The house wasn’t much, but it was a lot more than they could have hoped for in their native Mexico, and they were proud to call themselves homeowners—dueños de su propia casa.1 In many respects the Rodriguez family was an American success story—they had come to this country with nothing more than what they could carry in a knapsack, and now they were genuine title-holders of the American Dream. But they worried about their son, and not without reason. Unlike his parents, Carlos had a shot at an education that could bring better options than they had, but he was vulnerable to the distractions of the street and often found himself cutting class and getting into little problems at school—problems that seemed to grow as he developed a reputation as a “troublemaker.”

Andrés was in many ways Carlos’s opposite. Andrés’s family wasn’t as successful as Carlos’s. His mother was born in the United States, graduated from high school, and attended a couple of years of community college. But after three children, her first marriage had ended in divorce. She remarried an undocumented European immigrant who had difficulty finding steady work. With the family depending mostly on her income from a paper route and a fast-food job, they struggled to stay afloat economically. Andrés often woke up in the early hours of the morning to help his mother with the paper route, then went to school with barely four or five hours of sleep. Nonetheless, he maintained a high grade point average and appeared to be headed for a bright future. He wanted to go to college and vowed to help his friends get there with him. Few people worried about him—he was level-headed, responsible, and focused on school.

Carlos and Andrés would come to have much more in common, however, than most people might imagine. Growing up Latino and working-class or poor in the United States means that opportunity can be more apparent than real and that opportunities offered almost every middle-class kid from the suburbs could be out of reach for a chamaco from the barrio. What happens to Carlos and Andrés, however, is increasingly important for everyone else sharing this nation with them, because this country’s future is predicated to a large extent on how well or how poorly these young people fare in our education system.

A little more than a generation ago, most U.S. students were of European background and went to school mostly with other students like themselves. In 1972, almost 80 percent of K–12 students were reported to be non-Hispanic white; African Americans accounted for about 15 percent of the school-age population, and were still highly concentrated in the South. With a few exceptions, Latinos were mostly unheard of outside the Southwest and a few pockets in the East, and less than 1 percent of the K–12 population was Asian. The baby boomers were moving through high school and into college in unprecedented numbers, and they were pressuring society to take the first real steps toward acknowledging and accepting ethnic diversity. Sweeping civil rights laws had recently been passed, and many youth had coalesced around their opposition to the war in Vietnam, as well as what they perceived to be other societal injustices, including racial discrimination.

Fast forward to the beginning of the twenty-first century. The baby boomers are now all grown up with a new generation of children of their own completing high school and going on to college in unprecedented numbers. In 2005, less than 58 percent of the K–12 population was of European descent. African Americans had increased slightly from 15 percent to about 16 percent of the K–12 population, but the Latino population had quadrupled—from about 5 percent to almost 20 percent—and Asians had become a significant national presence, now 3.7 percent.2 By the last decade of the twentieth century, virtually all of the major urban school districts had become “majority minority”—overwhelmingly black and brown. Moreover, in 2003 the West became the first region in the United States to be majority minority, with a majority that is largely brown. Only 46 percent of school-age children were European American, while 54 percent were minorities. By 2025, the U.S. Census Bureau predicts that one of every four students will be Latino, and that the population will continue to become more Hispanic. Latino youth are inextricably linked to the nation’s future.

The history of the United States is one of different groups—often immigrants, but not always—finding their place in society and the economy. For most, there has been a period of difficulty and adjustment during which both the ethnic group members and the existing society adapted to each other. And the adjustment has been more difficult for some groups than others. Italians, for example, fared much more poorly in school than many other immigrant students, and for a time there was considerable concern about whether Jewish immigrants would be able to compete academically.3 Yet these groups were eventually integrated into the mainstream society and those students are at no greater risk academically than any other European-origin group.

The situation is not as hopeful this time around. Evidence suggests that there may be real reason for concern—even alarm—about the state of the growing Latino school-age population. Latino students are underachieving at high and consistent rates, and while children of immigrants, and their grandchildren, do indeed improve their educational attainment with each generation, there appears to be a ceiling effect that results in little or no improvement after the third generation (and a number of researchers argue after the second) for some Latino immigrant groups.4 At a time when college has become the new critical threshold for entry into the middle class, the overwhelming majority of Latinos do not attend degree-granting colleges—and those who do attend, often don’t graduate. Thus Latinos remain the most undereducated major population group in the country. In making this statement, we acknowledge fully the great diversity in the group labeled “Latino,” and note that Cuban Americans actually outperform white students in college attainment. Individuals of Mexican origin, however, who comprise about two-thirds of all U.S. Latinos, fare exceptionally poorly in the public schools, as do Puerto Ricans, the second largest subgroup. Never before have we been faced with a population group on the verge of becoming the majority in significant portions of the country that is also the lowest performing academically. And never before has the economic structure been less forgiving to the undereducated.

The Achievement Dilemma

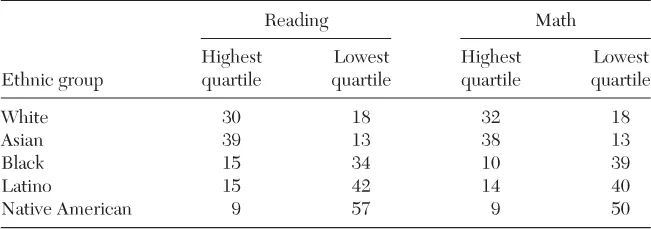

Achievement differences among ethnic groups are consistent and large at the earliest stages of formal academic assessment. For example, in a national sample of America’s kindergartners, African American, Latino, and Native American children were found to be much more likely to score in the lowest quartile on a test of early reading and math skills than either white or Asian students.5 And with the exception of Native American students, Latinos were the most likely of all groups to fall into the lowest quartile of performance (see Table 1.1).

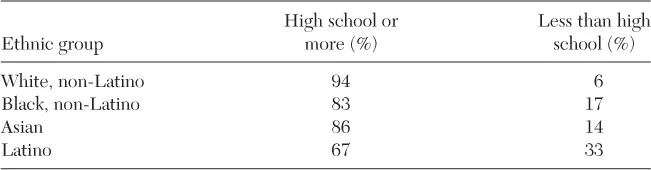

According to U.S. Department of Education researchers, children’s academic performance increases as a function of mothers’ education across all ethnic groups. But Latino mothers have much less education than mothers from all other major groups (see Table 1.2). Thus the lower educational background of Latino youngsters’ parents appears to be a significant factor in these children’s early low academic performance, and continues to affect their achievement throughout their later education.6

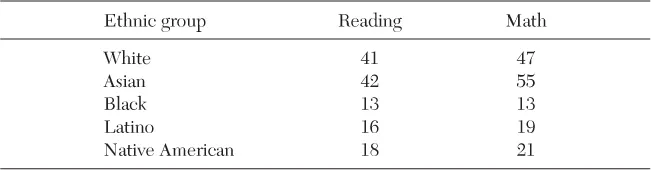

The National Center for Education Statistics conducts a periodic assessment of academic achievement of the nation’s fourth-, eighth-, and twelfth-graders. Known as the Nation’s Report Card, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests a representative sample of students in all fifty states in reading and math. Scores on NAEP exams are categorized into three levels: basic, which signifies rudimentary, partial mastery of the subject at grade level; proficient, which represents full mastery of the subject at grade level; and advanced, which is superior performance normally considered above grade level. Table 1.3 shows the percentages of fourth grade students from different ethnic groups who scored at or above proficient in reading and mathematics in 2005. The discrepancies by ethnicity found here are similar to those noted for kindergartners. While 41 percent of white students in the fourth grade scored at or above proficient, only 13 percent of African Americans and 16 percent of Latinos reached this level of competency in reading. Again, Latinos’ mathematics scores paralleled their reading scores, and are very different from the scores for white and Asian students.

Table 1.1 Percentage of kindergartners scoring at highest and lowest quartiles in math and reading, 1998

Source: West, Denton, and Germino-Hausken 2000.

Table 1.2 Mothers’ education level, by ethnicity, 1998

Source: West, Denton, and Germino-Hausken 2000.

Another recent national study that looked at the educational progress of “at risk” students in Title I schools—those schools designated as needing special help because of poverty conditions and overall low academic performance—found similar ethnic discrepancies in both reading and mathematics on the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills (CTBS).7 But the most troubling finding of this study was the extent to which low-income students continued to disengage from school throughout the elementary years. That is, their achievement declined with each succeeding year. The researchers noted that among children who were the highest achieving when they entered school, “the process of disengagement begins at first grade and continues through the sixth grade [and] . . . African American students who began third grade at or above the 50th percentile disengage at a significantly faster rate than comparable White students.”8 These researchers focused on schools with high percentages of black students and did not investigate the academic achievement of Latinos separately, but it appears likely that this pattern would hold for academically talented Latinos, because they tend to score similarly to blacks and experience many of the same schooling conditions.

Table 1.3 Percentage of fourth grade students proficient in reading and math, by ethnicity, 2005

Source: Perie, Grigg, and Donahue 2005; Perie, Grigg, and Dion 2005.

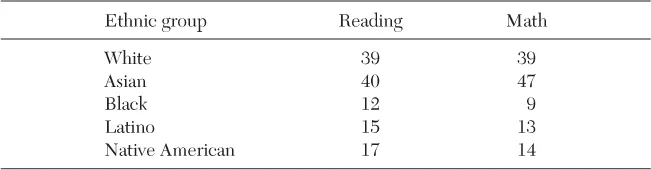

By the eighth grade, scores for all groups drop, but Latinos remain significantly behind most other groups; 39 percent of white students score at or above proficient, whereas only 15 percent of Latinos are able to reach this level of reading competence. NAEP mathematics scores for 2005 reveal an even more troubling picture. While 39 percent of white students and 47 percent of Asians scored at or above proficient, only 9 percent of African Americans and 13 percent of Latinos scored this high (see Table 1.4).

Although grade point averages are known to vary greatly among schools that are more and less rigorous in their demands on students and the difficulty level of the courses they offer, it is nonetheless a useful measure of comparative performance among groups.9 While minority students—and Latino students in particular—tend to go to schools and be assigned to classes where standards are often lower and teacher and other resources weaker, they also receive lower grades than either white or Asian students (see Table 1.5). Why would this be so if the classes, on the whole, are easier? A history of underpreparation is undoubtedly part of the problem, but also likely to blame are lowered aspirations and little understanding by Latino students and families of the connection between good grades and future opportunities.10 Whatever the cause, persistently lower grades result in fewer opportunities for students and lower their chances of gaining access to college and other sources of postsecondary education.

Table 1.4 Percentage of eighth grade students at or above proficient in reading and math, by ethnicity, 2005

Source: Perie, Grigg, and Donahue 2005; Perie, Grigg, and Dion 2005.

The high school dropout rate is yet another indicator of the relative educational performance of students from different ethnic groups. But there are many ways to count dropout students (or the inverse—graduates), and most data on this topic are suspect because of variations in reporting among schools, districts, and states. The National Center for Education Statistics tallies dropouts and graduates several different ways, using the Common Core of Data reported to the Department of Education; it estimates that in 2005 about 70 percent of Latinos (Hispanics) graduated from public high schools in the United States after four years in high school, an increase from the rate of about 56 percent documented in 1972.11 These figures, however, do not take into account those students who drop out even before ninth grade, and as noted earlier, they rely on reporting systems that are sometimes suspect. For example, recent analyses of dropouts in the Boston public schools show that from 2003 to 2006, between 3 and 4.8 percent of Latino students dropped out annually in the sixth through eighth grades. That is, as many as 14.4 percent of these students had exited before ever entering high school.12

Table 1.5 Grade point averages for high school graduates, 2000

Ethnicity | High school GPA |

Asian | 3.20 |

White | 3.01 |

Latino | 2.80 |

Black | 2.63 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences 2000.

Analyses reported by the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University and the Urban Institute, too, call into question the more generous graduation estimates and further suggest that improvements over time may, in fact, be illusory.13 Using what they contend is a superior method of data collection, which “chases” students who have left school but were formerly unaccounted for in the dropout numbers, these investigators argue that an estimated 68 percent of all students who begin high school in the ninth grade in the United States graduate with a regular diploma four years later. For white students the rate is about 75 percent, but for Latinos, it is only about 53 percent. That is, almost...