eBook - ePub

Ancient Greece

From the Archaic Period to the Death of Alexander the Great

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Greece

From the Archaic Period to the Death of Alexander the Great

About this book

From Archaic times to the reign of Alexander the Great, Greek unity was tenuous, yet Ancient Greece was a place where culture flourished and intellectual achievement knew no bounds. Ancient Greek ideas on philosophy, politics, science, and the arts anticipate many of our own, and in some ways, remain unparalleled today. This book recounts the events that were instrumental to the development of this storied civilization and the indelible legacies it has left behind. A detailed appendix supplements the narrative with in-depth discussion on the Pre-Greek societies that fueled the imagination and gave birth to an enduring body of Greek mythology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Greece by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kathleen Kuiper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

This book discusses the period following Mycenaean civilization, which ended in about 1200 BC, to the death of Alexander the Great, in 323 BC. This encompasses the Archaic and Classical periods. This was a time of political, philosophical, artistic, and scientific achievements that formed a legacy with unparalleled influence on Western civilization.

The Archaic period represents an era of artistic development in Greece from roughly 650 to 480 BC, the date of the Persian sack of Athens. It was preceded by a period—often called a Dark Age—between the catastrophic end of the Mycenaean civilization and about 900 BC. This era was a time about which Greeks of the Classical Age (roughly 500 to 320 BC) had confused and false notions.

THE POST-MYCENAEAN PERIOD AND LEFKANDI

An example of this lack of understanding of the preceding period can be found in the work of Thucydides (c. 460–c. 404 BC), the great ancient historian of the fifth century BC. Thucydides wrote a sketch of Greek history from the Trojan War to his own day in which he notoriously fails, in the appropriate chapter, to signal any kind of dramatic rupture. (He does, however, speak of Greece “settling down gradually” and colonizing Italy, Sicily, and what is now western Turkey. This surely implies that Greece was settling down after something.) Thucydides does indeed display sound knowledge of the series of migrations by which Greece was resettled in the post-Mycenaean period. The most famous of these was the “Dorian invasion,” which the Greeks called, or connected with, the legendary “return of the descendants of Heracles.” Although much about that invasion is problematic—it left little or no archaeological trace at the point in time where tradition puts it—the problems are of no concern here. Important for the understanding of the Archaic and Classical periods, however, is the powerful belief in Dorianism as a linguistic and religious concept. Thucydides casually but significantly mentions soldiers speaking the “Doric dialect” in a narrative about ordinary military matters in the year 426: this is a surprisingly abstract way of looking at the subdivisions of the Greeks because it would have been more natural for a fifth-century Greek to identify soldiers by cities. Equally important to the understanding of this period is the hostility to Dorians, usually on the part of Ionians, another linguistic and religious subgroup, whose most famous city was Athens. So extreme was this hostility that Dorians were prohibited from entering Ionian sanctuaries. Extant today is a fifth-century example of such a prohibition, an inscription from the island of Paros.

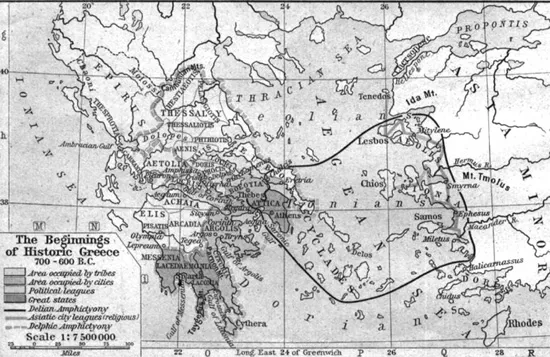

During the Archaic period, Greece comprised not only mainland and islands, but also colonies on the coast of what is now Turkey. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin

Phenomena such as the tension between Dorians and Ionians that have their origins in the Dark Age are a reminder that Greek civilization did not emerge either unannounced or uncontaminated by what had gone before. The Dark Age itself is beyond the scope of this book. One is bound to notice, however, that archaeological finds tend to call into question the whole concept of a Dark Age by showing that certain features of Greek civilization once thought not to antedate about 800 BC can actually be pushed back by as much as two centuries. One example, chosen for its relevance to the emergence of the Greek city-state, or polis, will suffice. In 1981 archaeology pulled back the curtain on the “darkest” phase of all, the Protogeometric Period (c. 1075–900 BC), which takes its name from the geometric shapes painted on pottery. A grave, rich by the standards of any period, was uncovered at a site called Lefkandi on Euboea, the island along the eastern flank of Attica (the territory controlled by Athens). The grave, which dates to about 1000 BC, contains the (probably cremated) remains of a man and a woman. The large bronze vessel in which the man’s ashes were deposited came from Cyprus, and the gold items buried with the woman are splendid and sophisticated in their workmanship. Remains of horses were found as well; the animals had been buried with their snaffle bits, mouthpieces that help riders control horses. The grave was within a large collapsed house, whose form anticipates that of the Greek temples two centuries later. Previously it had been thought that these temples were one of the first manifestations of the “monumentalizing” associated with the beginnings of the city-state. Thus this find, and those made in a set of nearby cemeteries in the years before 1980 attesting further contacts between Egypt and Cyprus between 1000 and 800 BC, are important evidence. They show that one corner of one island of Greece, at least, was neither impoverished nor isolated in a period usually thought to have been both. The difficulty is to know just how exceptional Lefkandi was, but in any view it has revised former ideas about what was and what was not possible at the beginning of the first millennium BC.

“COLONIZATION” AND CITY-STATE FORMATION

Thucydides, as was mentioned earlier, wrote about Greek migration and colonization of Italy, Sicily, and modern-day western Turkey. The term colonization, although it may be convenient and widely used, is misleading. When applied to Archaic Greece, it should not necessarily be taken to imply the state-sponsored sending out of definite numbers of settlers, as the later Roman origin of the word implies. For one thing, it will be seen that state formation may itself be a product of the “colonizing” movement.

The first “date” in Greek history is 776 BC, the year of the first Olympic Games. It was computed by a fifth-century-BC researcher named Hippias. This man originally came from Elis, a place in the western Peloponnese in whose territory Olympia itself is situated. This date and the list of early victors, transmitted by another literary tradition, are likely to be reliable, if only because the list is so unassuming in its early reaches. That is to say, local victors predominate, including some Messenians. Messene lost its independence to neighbouring Sparta during the course of the eighth century, and this fact is an additional guarantee of the reliability of the early Olympic victor list: Messenian victors would hardly have been invented at a time when Messene as a political entity had ceased to exist. Clearly, then, record keeping and organized activity involving more than one community and centring on a sanctuary, such as Olympia, go back to the early eighth century. (Such competitive activity is an example of what has been called “peer-polity interaction.”) Records imply a degree of literacy, and here too the tradition about the eighth century has been confirmed by finds. A cup, bearing the inscription in Greek in the Euboean script “I am the cup of Nestor,” can be securely dated to before 700 BC. It was found at an island site called Pithekoussai (Ischia) on the Bay of Naples.

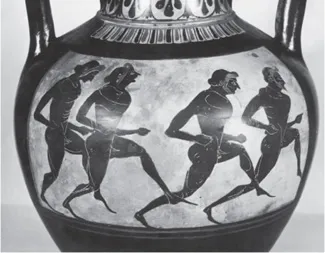

OLYMPIC GAMES

The athletic festival known as the Olympic Games originated in ancient Greece and was revived in the late 19th century. Before the 1970s the games were officially limited to competitors with amateur status, but in the 1980s many events were opened to professional athletes. Currently the games are open to all, even the top professional athletes in basketball and football (soccer). The ancient Olympic Games included several of the sports that are now part of the Summer Games program, which at times has included events in as many as 32 different sports. In 1924 the Winter Games were sanctioned for winter sports. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition.

Greek vase showing Olympic athletes in a race. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Of all the early athletic festivals (including the Olympic Games, held at Olympia; the Pythian Games at Delphi; the Nemean Games at Nemea; and the Isthmian Games, held near Corinth), the Olympic Games were the most famous. Held every four years between August 6 and September 19, they occupied such an important place in Greek history that in late antiquity historians measured time by the interval between them—an Olympiad. The Olympic Games, like almost all Greek games, were an intrinsic part of a religious festival. They were held in honour of Zeus at Olympia by the city-state of Elis in the northwestern Peloponnese. The first Olympic champion listed in the records was Coroebus of Elis, a cook, who won the sprint race in 776 BC. Notions that the Olympics began much earlier than 776 BC are founded on myth, not historical evidence. According to one legend, for example, the games were founded by Heracles, son of Zeus and Alcmene.

OVERSEAS PROJECTS

The early overseas activity of the Euboeans has already been remarked upon in connection with the discoveries at Lefkandi. They were the prime movers in the more or less organized—or, at any rate, remembered and recorded—phase of Greek overseas settlement. (Euboean priority can be taken as absolutely certain because archaeology supports the literary tradition of the Roman historian Livy and others: Euboean pottery has been found both at Pithekoussai to the west and at the Turkish site of Al-Mina to the east.) This more organized phase began in Italy c. 750 and in Sicily in 734 BC. Its episodes were remembered, perhaps in writing, by the colonies themselves. The word organized needs to be stressed because various considerations make it necessary to push back beyond this date the beginning of Greek colonization. First, it is clear from archaeological finds, such as the Lefkandi material, and from other new evidence that the Greeks had already, before 750 or 734, confronted and exchanged goods with the inhabitants of Italy and Sicily. Second, Thucydides says that Dark Age Athens sent colonies to Ionia, and archaeology bears this out—however much one discounts for propagandist exaggeration by the imperial Athens of Thucydides’ own time of its prehistoric colonizing role. However, after the founding of Cumae (a mainland Italian offshoot of the island settlement of Pithekoussai) c. 750 BC and of Sicilian Naxos and Syracuse in 734 and 733, respectively, there was an explosion of colonies to all points of the compass. The only exceptions were those areas, such as pharaonic Egypt or inner Anatolia, where the inhabitants were too militarily and politically advanced to be easily overrun.

One may ask why the Greeks suddenly began to launch these overseas projects. It seems that commercial interests, greed, and sheer curiosity were the motivating forces. An older view, according to which Archaic Greece exported its surplus population because of an uncontrollable rise in population, must be regarded as largely discredited. In the first place, the earliest well-documented colonial operations were small-scale affairs, too small to make much difference to the situation of the sending community (the “metropolis,” or mother city). That is certainly true of the colonization of Cyrene, in North Africa, from the island of Thera (Santorin): on this point an inscription has confirmed the classic account by the fifth-century Greek historian Herodotus. In the second place, population was not uncontrollable in principle: methods such as infanticide and contraception were available. Considerations of this kind much reduce the evidential value of discoveries establishing, for example, that the number of graves in Attica and the Argolid (the area centred on Argos) increased dramatically in the later Dark Age or that there was a serious drought in eighth-century Attica (this is the admitted implication of a number of dried-up wells in the Athenian agora, or civic centre). In fact, no single explanation for the colonizing activity is plausible. Political difficulties at home might sometimes be a factor, as, for instance, at Sparta, which in the eighth century sent out a colony to Taras (Tarentum) in Italy as a way of getting rid of an unwanted half-caste group. Nor can one rule out simple craving for excitement and a desire to see the world. The lyric poetry of the energetic and high-strung poet Archilochus, a seventh-century Parian involved in the colonization of Thasos, shows the kind of lively minded individual who might be involved in the colonizing movement.

So far, the vague term community has been used for places that sent out colonies. Such vagueness is historically appropriate because these places themselves were scarcely constituted as united entities, such as a city, or polis. For example, it is a curious fact that Corinth, which in 733 colonized Syracuse in Sicily, was itself scarcely a properly constituted polis in 733. (The formation of Corinth as a united entity is to be put in the second half of the eighth century, with precisely the colonization of Syracuse as its first collective act.)

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE POLIS

The name given to polis formation by the Greeks themselves was synoikismos, literally a “gathering together.” Synoikismos could take one or both of two forms—it could be a physical concentration of the population in a single city or an act of purely political unification that allowed the population to continue living in a dispersed way. The classic discussion is by Thucydides, who distinguishes between the two kinds of synoikismos more carefully than do some of his modern critics. He makes the correct point that Attica was politically synoecized (gathered into larger units) at an early date but not physically synoecized until 431 BC when Pericles as part of his war policy brought the large rural population behind the city walls of Athens. A more extreme instance of a polis that was never fully synoecized in the physical sense was Sparta, which, as Thucydides elsewhere says, remained “settled by villages in the old Greek way.” It was an act of conscious arrogance, a way of claiming to be invulnerable from attack and not to need the walls that Thucydides again and again treats as the sign and guarantee of civilized polis life. The urban history of Sparta makes an interesting case history showing that Mycenaean Sparta was not so physically or psychologically secure as its Greek and Roman successors. The administrative centre of Mycenaean Sparta was probably in the Párnon Mountains at the excavated site of the Menelaion. Then Archaic and Classical Sparta moved down to the plain. Byzantine Sparta, more insecure, moved out of the plain again to perch on the site of Mistra on the opposite western mountain, Taygetos. Finally, modern Sparta is situated, once again peacefully and confidently, on its old site on the plain of the river Eurotas.

The enabling factors behind the beginnings of the Greek polis have been the subject of intense discussion. One approach connects the beginnings of the polis with the first monumental buildings, usually temples like the great early eighth-century temple of Hera on the island of Samos. The concentration of resources and effort required for such constructions presupposes the formation of self-conscious polis units and may actually have accelerated it. As stated above, however, the evidence from Lefkandi makes it hard to see the construction of such monumental buildings as a sufficient cause for the emergence of the polis, a process or event nobody has yet tried to date as early as 1000 BC.

Another related theory argues that the birth of the Greek city was signaled by the placing of rural sanctuaries at the margins of the territory that a community sought to define as its own. This fits admirably a number of Peloponnesian sanctuaries. For instance, the temple complex of Hera staked out a claim, on the part of relatively distant Argos, to the plain stretching between city and sanctuary, and the Corinthian sanctuary on the promontory of Perachora, also dedicated to Hera, performed the same function. Yet there are difficulties. It seems that the Isthmia sanctuary, which at first sight seems a good candidate for another Corinthian rural sanctuary, was already operational as early as 900 BC, in the Protogeometric Period, and this date is surely too early for polis formation. Nor does the theory easily account for the rural temple of the goddess Aphaea in the middle of Aegina. The sanctuary is admittedly a long way from the town of Aegina, but Aegina is an island, and there is no obvious neighbour against whom territorial claims could plausibly have been asserted. Finally, a theory that has to treat the best-known polis, namely Athens, and Attica as in every respect exceptional is not satisfactory: there is no Athenian equivalent of the Argive Heraeum.

A third theory attacks the problem of the beginnings of the polis through burial practice. In the eighth century (it is said) formal burial became more generally available, and this “democratization” of burial is evidence for a fundamentally new attitude toward society. The theory seeks to associate the new attitude with the growth of the polis. There is, however, insufficient archaeological and historical evidence for this view (which involves an implausible hypothesis that the process postulated was discontinuous and actually reversed for a brief period at a date later than the eighth century). Moreover, it is vulnerable to the converse objection as that raised against the second theory: the evidence for the third theory is almost exclusively Attic, and so, even if it were true, it would explain Athens and only Athens.

Fourth, one may consider a theory whose unspoken premise is a kind of “geographic determinism.” Perhaps the Greek landscape itself, with its small alluvial plains often surrounded by defensible mountain systems, somehow prompted the formation of small and acrimonious poleis, endlessly going to war over boundaries. This view has its attractions, but the obvious objection is that, when Greeks went to more open areas such as Italy, Sicily, and North Africa, they seem to have taken their animosities with them. This in turn invites speculations of a psychologically determinist sort. One has to ask, without hope of an answer, whether the Greeks were naturally particularist.

A fifth enabling factor that should be borne in mind is the influence of the colonizing movement itself. The political structure of the metropolis, or sending city, may sometimes have been inchoate. The new colony, however, threatened by hostile native neighbours, rapidly had to “get its act together” if it was to be a viable cell of Hellenism on foreign soil. This effort in turn affected the situation in the metropolis because Greek colonies often kept close religious and social links with it. A fourth-century inscription, for instance, attests close ties between Miletus and its daughter city Olbia in the Black Sea region. Here, however, as so often in Greek history, generalization is dangerous. Some mother-daughter relationships, like that between Corinth and Corcyra (Corfu), were bad virtually from the start.

A related factor is Phoenician influence (related, because the early Phoenicians were great colonizers, who must often h...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Archaic Period

- Chapter 2: Classical Greek Civilization: The Persian Wars

- Chapter 3: Classical Greek Civilization: The Athenian Empire

- Chapter 4: Classical Greek Civilization: The Peloponnesian War

- Chapter 5: Greek Civilization in the Fifth Century BC

- Chapter 6: Greece in the Fourth Century BC

- Appendix: Pre-Greek Aegean Civilizations

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index