- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bacteria and Viruses

About this book

The sometimes insidious effects of bacterial diseases and viral infections can obscure the incredible significance of the microscopic organisms that cause them. Bacteria and viruses are among the oldest agents on Earth and reveal much about the planet's past and evolution. Moreover, their utility in the development of new cures and treatments signals much about the future of biotechnology and medicine. This penetrating volume takes readers under the lens of a microscope to explore the structure, nature, and role of both bacteria and viruses as well as all other aspects of microbiology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bacteria and Viruses by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kara Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biochemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Bacterial Morphology and Reproduction

In the hidden world of microscopic things, bacteria and viruses are among the most amazing and the most mysterious. Knowledge of the existence of life invisible to the naked eye first emerged in the 17th century, with the invention of the microscope by Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Among the various types of “animalcules,” or little animals, that Leeuwenhoek discovered with the aid of his microscope were the single-celled organisms now known as bacteria.

In Leeuwenhoek’s time, these microscopic forms were the subjects of intense scientific debate. Prior to bacteria, scientists had hypothesized that living organisms developed from nonliving matter in a process called spontaneous generation. In the 19th century, however, spontaneous generation was overturned by French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, whose research on bacteria published in 1861 helped to establish the principle of biogenesis—that organisms arise only through the reproduction of other organisms. Biogenesis also supported germ theory, the idea that disease can arise as a result of invasion of the body by microorganisms. Biogenesis and germ theory represented the very early stages of scientists’ understanding of bacteria, and in subsequent decades far more became known about these amazing microbes, particularly concerning their roles in Earth’s various ecosystems, such as contributing to the breakdown of organic matter in soils and sharing in symbiotic relationships with other organisms.

In the 1890s scientists speculated about the existence of a very different group of microscopic agents, which later came to be known as viruses. Viruses are much smaller than bacteria, but they are also responsible for causing a variety of diseases in plants and animals, including humans. Researchers have long debated whether or not viruses are living or nonliving entities, since outside of a living cell a virus is an inactive particle, but within an appropriate host cell it becomes active, capable of taking over the cell’s metabolic machinery for the production of new virus particles (virions). Most viruses inflict harm on host organisms, and there are a number of widespread pathogenic (disease-causing) viruses known to humans. Among these pathogens is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a disease in which the immune system is gradually destroyed, over the course of years, as a result of viral infection. The widespread transmission of HIV is of global concern, and despite tremendous efforts in drug discovery and medicine, a cure for infection is yet to be found.

Because the role of bacteria and viruses in human disease is so significant, microbiology—an area of study concerned with the structure, function, classification, and manipulation of microscopic entities—is at the forefront of modern science. Ongoing research efforts are focused largely on obtaining a better understanding of the distribution in nature of bacteria and viruses and their role in disease and on learning more about their evolution and natural histories. Indeed, the primitive ancestors of bacteria, known as the archaea, are believed to be representatives of some of Earth’s earliest life-forms; studies have indicated that the first archaea appeared on Earth about 3.5 billion years ago, followed by the first bacteria, the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), some 3 billion years ago. Although the evolution of viruses is much less clear, they are believed to have emerged about 200 million years ago. Thus, bacteria and viruses are significant not only for their role in disease but also for their role in the evolution of life on early Earth.

Bacteria are microscopic single-celled organisms that live in enormous numbers in almost every environment on the surface of Earth, from deep-sea vents to the digestive tracts of humans. They are characterized morphologically by the absence of a membrane-bound nucleus and other internal structures and are therefore ranked among the unicellular life-forms called prokaryotes. Prokaryotes are the dominant living creatures on Earth, having been present for perhaps three-quarters of Earth history and having adapted to almost all available ecological habitats.

As a group, the bacteria display exceedingly diverse metabolic capabilities and can use almost any organic compound, and some inorganic compounds, as a food source. Some bacteria can cause diseases in humans, animals, or plants, but most are harmless and are beneficial ecological agents whose metabolic activities sustain higher life-forms. Other bacteria are symbionts of plants and invertebrates, where they carry out important functions for the host, such as nitrogen fixation and cellulose degradation. Without prokaryotes, soil would not be fertile, and dead organic material would decay much more slowly. Some bacteria are widely used in the preparation of foods, chemicals, and antibiotics. Studies of the relationships between different groups of bacteria continue to yield new insights into the origin of life on Earth and the mechanisms of evolution.

BACTERIA AS PROKARYOTES

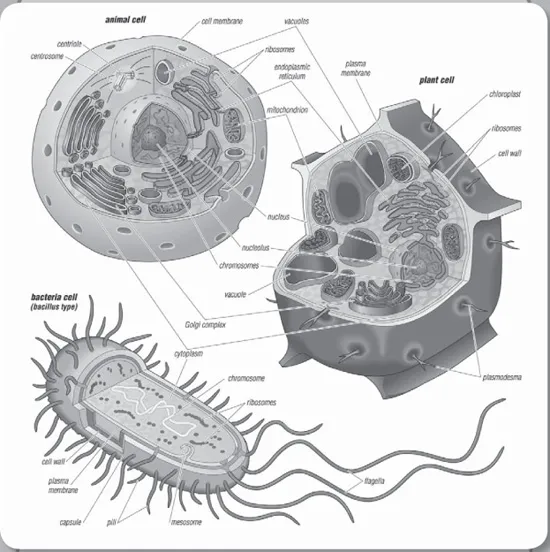

All living organisms on Earth are made up of one of two basic types of cells: eukaryotic cells, in which the genetic material is enclosed within a nuclear membrane, or prokaryotic cells, in which the genetic material is not separated from the rest of the cell. Traditionally, all prokaryotic cells were called bacteria and were classified in the prokaryotic kingdom Monera. However, their classification as Monera, equivalent in taxonomy to the other kingdoms—Plantae, Animalia, Fungi, and Protista—understated the remarkable genetic and metabolic diversity exhibited by prokaryotic cells relative to eukaryotic cells. In the late 1970s American microbiologist Carl Woese pioneered a major change in classification by placing all organisms into three domains—Eukarya, Bacteria (originally called Eubacteria), and Archaea (originally called Archaebacteria)—to reflect the three ancient lines of evolution. The prokaryotic organisms that were formerly known as bacteria were then divided into two of these domains, Bacteria and Archaea. Bacteria and Archaea are superficially similar; for example, they do not have intracellular organelles, and they have circular DNA. However, they are fundamentally distinct, and their separation is based on the genetic evidence for their ancient and separate evolutionary lineages, as well as fundamental differences in their chemistry and physiology. Members of these two prokaryotic domains are as different from one another as they are from eukaryotic cells.

Bacterial cells differ from animal cells and plant cells in several ways. One fundamental difference is that bacterial cells lack intracellular organelles, such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, and a nucleus, which are present in both animal cells and plant cells. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Prokaryotic cells (i.e., Bacteria and Archaea) are fundamentally different from the eukaryotic cells that constitute other forms of life. Prokaryotic cells are defined by a much simpler design than is found in eukaryotic cells. The most apparent simplification is the lack of intracellular organelles, which are features characteristic of eukaryotic cells. Organelles are discrete membrane-enclosed structures that are contained in the cytoplasm and include the nucleus, where genetic information is retained, copied, and expressed; the mitochondria and chloroplasts, where chemical or light energy is converted into metabolic energy; the lysosome, where ingested proteins are digested and other nutrients are made available; and the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, where the proteins that are synthesized by and released from the cell are assembled, modified, and exported. All of the activities performed by organelles also take place in bacteria, but they are not carried out by specialized structures. In addition, prokaryotic cells are usually much smaller than eukaryotic cells. The small size, simple design, and broad metabolic capabilities of bacteria allow them to grow and divide very rapidly and to inhabit and flourish in almost any environment.

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells differ in many other ways, including lipid composition, structure of key metabolic enzymes, responses to antibiotics and toxins, and the mechanism of expression of genetic information. Eukaryotic organisms contain multiple linear chromosomes with genes that are much larger than they need to be to encode the synthesis of proteins. Substantial portions of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) copy of the genetic information (deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA) are discarded, and the remaining messenger RNA (mRNA) is substantially modified before it is translated into protein. In contrast, bacteria have one circular chromosome that contains all of their genetic information, and their mRNAs are exact copies of their gene and are not modified.

DIVERSITY OF STRUCTURE OF BACTERIA

Although bacterial cells are much smaller and simpler in structure than eukaryotic cells, the bacteria are an exceedingly diverse group of organisms that differ in size, shape, habitat, and metabolism. Much of the knowledge about bacteria has come from studies of disease-causing bacteria, which are more readily isolated in pure culture and more easily investigated than are many of the free-living species of bacteria. It must be noted that many free-living bacteria are quite different from the bacteria that are adapted to live as animal parasites. Thus, there are no absolute rules about bacterial composition or structure, and there are many exceptions to any general statement.

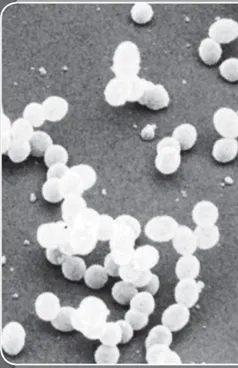

Individual bacteria can assume one of three basic shapes: spherical (coccus), rodlike (bacillus), or curved (vibrio, spirillum, or spirochete). Considerable variation is seen in the actual shapes of bacteria, and cells can be stretched or compressed in one dimension. Bacteria that do not separate from one another after cell division form characteristic clusters that are helpful in their identification. For example, some cocci are found mainly in pairs, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, a pneumococcus that causes bacterial lobar pneumonia, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a gonococcus that causes the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhea. Most streptococci resemble a long strand of beads, whereas the staphylococci form random clumps (the name “staphylococci” is derived from the Greek word staphyle, meaning “cluster of grapes”). In addition, some coccal bacteria occur as square or cubical packets. The rod-shaped bacilli usually occur singly, but some strains form long chains, such as rods of the corynebacteria, normal inhabitants of the mouth that are frequently attached to one another at random angles. Some bacilli have pointed ends, whereas others have squared ends, and some rods are bent into a comma shape. These bent rods are often called vibrios and include Vibrio cholerae, which causes cholera. Other shapes of bacteria include the spirilla, which are bent and rebent, and the spirochetes, which form a helix similar to a corkscrew, in which the cell body is wrapped around a central fibre called the axial filament.

The bacterium Streptococcus mutans is an example of a spherical (coccus) bacterium. This species of bacteria commonly aggregates into pairs and short chains. David M. Phillips/Visuals Unlimited

Bacteria are the smallest living creatures. An average-size bacterium, such as the rod-shaped Escherichia coli, a normal inhabitant of the intestinal tract of humans and animals, is about 2 micrometres (μm; millionths of a metre) long and 0.5 μm in diameter, and the spherical cells of Staphylococcus aureus are up to 1 μm in diameter. A few bacterial types are even smaller, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which is one of the smallest bacteria, ranging from about 0.1 to 0.25 μm in diameter; the rod-shaped Bordetella pertussis, which is the causative agent of whooping cough, ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 μm in diameter and 0.5 to 1 μm in length; and the corkscrew-shaped Treponema pallidum, which is the causative agent of syphilis, averaging only 0.15 μm in diameter but 10 to 13 μm in length. Some bacteria are relatively large, such as Azotobacter, which has diameters of 2 to 5 μm or more; the cyanobacterium Synechococcus, which averages 6 μm by 12 μm; and Achromatium, which has a minimum width of 5 μm and a maximum length of 100 μm, depending on the species. Gian...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Bacterial Morphology and Reproduction

- Chapter 2: Growth, Ecology, and Evolution of Bacteria

- Chapter 3: Types of Bacteria

- Chapter 4: Virus Morphology and Evolution

- Chapter 5: Cycles and Patterns of Viral Infection

- Chapter 6: Types of Viruses

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index